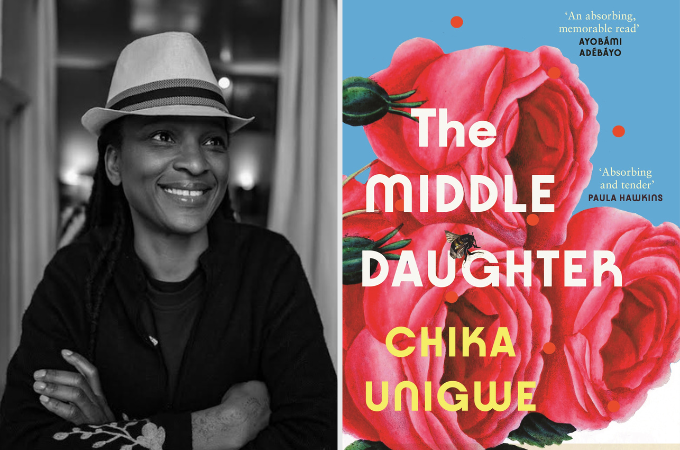

Chika Unigwe’s The Middle Daughter is a modern retelling of the story of Hades and Persephone. The story goes that Hades abducts Persephone and takes her to the underworld where she becomes the queen of the dead, ruling alongside him.

There are versions of the myth where Persephone’s mother intercedes on her behalf and essentially strikes a deal so that Persephone can leave the underworld for half the year. Unigwe is interested in the abduction part, not the part that normalizes patriarchal violence by negotiating with terrorists. She is interested in how Persephone might tell the story of her abduction differently. For Unigwe, Persephone’s version would invariably end happily.

The Middle Daughter is a powerfully affirming re-write of the classic story through the life of a young woman named Nani living in Enugu, Nigeria. At the most vulnerable moment in her life, she is lured into the arms of a sweet-talking preacher named Ephraim. The relationship quickly devolves and Nani finds herself trapped in an abusive marriage. But what drives the story is not whether Nani would leave her abuser or not (as Unigwe says in this interview, there was never a question about that) but how she leaves him. The Middle Daughter is, thus, the painful but empowering story of a woman who refused to stay.

This was an emotionally grueling book to read for the ways it arced Nani’s life along the unfolding of tragic experiences, which, I’d admit, made the ending so much more powerful, affirming, and satisfying. At the center of the story is a woman remembering her past. The story opens with her taking us all the way back to the beginning, to those moments when her life is essentially perfect. This perfection manifests in the pure joy of family life. In a household with three girls, Nani is the middle child. She grows up in an upper-middle class world, sheltered from the chaos of poverty and exploitation. This blissful existence and how it is lost is captured in the metaphor of the classic complete story:

Three girls. Udodi was the beginning, I was the middle, Ugo the conclusion. “You are my short story,” Doda said all the time. The perfect short story. But perfection never lasts, a sleight of hand and everything splinters, your whole life is upended. And then one day you are in someone else’s house wondering whether you will ever see your own three children again.”

Nani is right. The Aristotelian ideal of a whole story with perfectly interconnecting phases of beginning, middle, and an end has been one of the biggest lies of modern storytelling. As an ideal, it is not only impractical but gives us a false sense of transcendence. It makes us believe that life is only worthy when its messiness is pared and stuffed into a whole story. It also makes us less capable of surviving when things end up falling apart because they always do.

The beginning of the novel details the series of breaks that tears Nani’s family apart and finally leaves her vulnerable. The first break happens when her sister dies. The second when her father dies, bringing the family of five to three, leaving Nani with her mother and her younger sister. Her father’s death makes the most damage, leaving a crack that she, in spite her best efforts, cannot repair. It gnaws at her, throws her into the bottomless pit of depression, and, worst of all, makes her vulnerable to people who hunt for brokenness in others to use to their own advantage. That is how she meets Ephraim, the “sleight of hand” that come close to splintering her life beyond recognition. What could have become a love story quickly spirals into a nightmare.

The reason I took the novel everywhere I went, savoring every stolen minute I could spend reading it in the midst of my hectic schedule has everything to do with the story’s near perfect pacing. Unigwe’s deft modulation of tension and anticipation fueled my emotional reaction to Nani. Meeting Nani for the first time was like meeting a stranger and sensing the history they carried. You may not agree with some of the choices that Nani makes but one thing you can’t deny is the fact that she is a brilliant story teller. She likes to leave traces, cliff hangers, anticipatory cues as though to alert the reader that even though she is beginning from the beginning—when things were good—she is going to end up in a different place. She is the queen of the tease, and the way the story paces and arcs, letting Nani’s life unfold the way she wants is a joy to experience. It kept me glued to the page. And there is also something ingeniously feminist about a female character who controls what she wants to share with the reader and how.

I learned many things from reading this book. For example, I learned something about how fear works as a means of control. South African feminist scholar Pumla Dineo Gqola says in her book Female Fear Factory that fear is how society makes women’s bodies available for men to violate. In a different world where women are not brought up to fear for their reputation, their image, their lives, to fear what their mothers, friends, and society think of them, Ephraim would have had no power over Nani. She would not have felt compelled to stay with him in spite of all the red flags. Ephraim knows exactly what he is doing when he evokes and exploits the age-old fear instilled in women that their worth hangs on approval from a world that sees them as guilty for the mere fact of being woman. In a sense then, Unigwe takes us back to the basics of patriarchal violence, reminding us of some of its oldest tricks and fantasies but also how to neutralize this power.

As I read The Middle Daughter, Sarah Irabor’s idea of literary ancestry kept ringing in my ears. I love stories that remind me of other stories. Through the call and response of history, they speak to other stories in a shared language of aesthetic and spiritual connection. Reading Unigwe’s scathing representation of male power, in its blindness to the humanity of the other, I thought of Francis in Buchi Emecheta’s Second Class Citizen. In representing Ephraim, Unigwe does not caricaturize him. There is a clear sense of who he is and what drives him. But she also does not give his violence and his intentions so much space that it crowds out Nani’s story. Ultimately, the story is titled The Middle Daughter for a reason. It is Nani’s story and not that of her abuser.

Knowing Adah in Emecheta’s novel certainly helped me understand aspects of Nani that I would have missed. I thought of how African feminist writers have always had an unbending faith in their female characters, how they have always treated their suffering with the honesty it deserves but also given them this fierce capacity to dream and fight their way out of captivity. For me, The Middle Daughter takes up a beautiful space on the bookshelf of literary tradition next to other powerful narratives of African women telling stories about pain but also inventing worlds where they are able to live on their own terms.

This novel is about how things fall apart, how cracks form in the heart of the most beautiful things. Chinua Achebe was the one of the first to teach us that we learn the most about ourselves from stories about how we break than stories about how we are formed. This is not because suffering has any kind of mystical access to the truth of life but because, in breaking, we get to reassemble the self, life, the world. The Middle Daughter is about the splintering of the self that makes possible the remaking of one’s world.

It is in that sense that the novel truly re-imagines Persephone’s story. Where mythology asks Persephone to be content with her abduction, Unigwe asks us to imagine a world where she not only leaves Hades but also builds a new world for herself and those who come after her. Nani, like Persephone, is like many women who are escape artists, and this book is a celebration of their triumph. The Middle Daughter is a powerful story about the truest, most luxuriant feminist joy—the joy of freedom. I treasure the politics of optimism that suffuses the novel—how it asks us to fiercely believe in a feminist future where women, from Persephone to Nani, do escape the chokehold of patriarchy and do find their happy, feel-good ending.

*****

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions