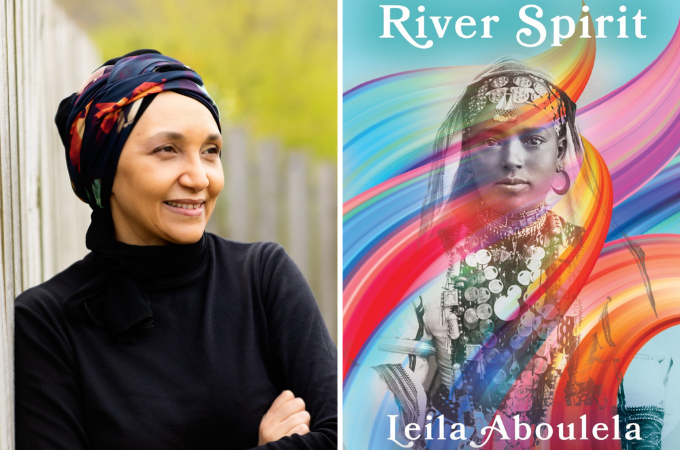

Rivers Spirit by Leila Aboulela was published on March 7th. A few weeks later on April 15, two dissenting Generals plunged Sudan into armed conflict. The latest report by the UN says that over five thousand people have been injured and 676 dead, not to mention the displacement of populations and the subjection of daily life to various hardships.

Rereading River Spirit in light of this on-going violence, has been deeply illuminating. I am further convinced in the power of fiction to provide a view into social experiences that is otherwise difficult to see. Aboulela’s novel is the story of another violent event in the history of Sudan, the Mahdist War, which took place in the 1880s. Though the circumstances of that war is different, when viewed through the lens of the current armed conflict, it shows the colonial and patriarchal context for history as a recurrence of violence. Placing both conflicts side by side shows that modern power, whether it is colonialism or post-colonial statehood, will always settle for violence as the primary language of political life.

In 1881, a Nubian Sufi religious leader named Muhammad Ahmad bin Abd Allah rose against the Turkish-Egyptian rule over Sudan and proclaimed himself savior of the Islamic world. Taking on the title Mahdi, he rallied support among Sudanese who were deeply unhappy under foreign rule due to heavy taxation and cultural domination. The Mahdi defeated the Egyptian army in some key battles and later the British in a highly publicized siege of Khartoum. Dying soon after he won the war, his son succeeded him and ruled Sudan for many years until he was ousted by the British in 1898. River Spirit covers this period, beginning a bit earlier in 1877 with the tragic experience that launches the heroine of the story into a journey through history.

Aboulela details the historical context of the war. She is your guide through the multiple interests, warring parties, political landscapes, and private lives. She paints the picture of late 19th century Sudan in vivid details: the excesses of the Ottoman empire, the desperation of the people, the bustling markets, abandoned towns, the violence of war, and the wreckage it leaves behind. She captures these moment with richly detailed historical set pieces that make the reader feel like they are in the middle of everything.

But history is nothing without its actors. Even though River Spirit is told from multiple perspectives, the main thread of the plot centers on two characters: a young merchant named Yaseen and Akuany, a young black woman, later known as Zamzam. Akuany is from Malakal, a city in present day South Sudan. During a slave raid on her town, both her parents were killed. But she escapes, thanks to a bond she shares with the White Nile, and ends up leaving town with her brother and Yaseen. The three of them stick together until they arrive at Yaseen’s sister’s house. Akuany, renamed Zamzam, becomes a slave in the house of an Ottoman imperial official while her brother is adopted by Yaseen’s sister. Everything—from their class difference to a raging war—conspires to separate Zamzam and Yaseen; yet, their worlds keep colliding, setting off a very unlikely love story that spans years and keeps the reader forever guessing.

Spirit River by Leila Aboulela gives us a different account of colonialism, reminding us that Africa’s story in modern times is not a monolith. Things Fall Apart canonized a particular way of telling the story of the colonial encounter. White man stumbles into an African village hidden in the depths of the forest and changes their world forever. This motif has been taken up by many authors and reproduced through the decades. Aboulela stages a different history. She shows Africans launching large-scale military campaigns in resistance to British colonial power and coming out triumphant. She examines the involvement of Egypt and the Ottoman Empire in the colonial rule of Sudan, an often overlooked aspect of modern imperialism. Most of all, she highlights the lives of ordinary individuals who played a role in the course of this history and secured a different fate for Sudan. By telling a different story of colonialism, River Spirit expands our understanding of Africa’s modern history in a way that feels urgent, particularly, in light of the current state of things in Sudan.

I want to return to Zamzam, who is the emotional center of the story. Aboulela got the idea for Zamzam’s character while rifling through the Sudan archives at Durham University. She found a document about an enslaved woman who ran away to her former master after stealing from her mistress. Intrigued by the mysterious circumstances of this incident, she crafts Zamzam’s story and fills in the details of how she became enslaved. It is important to acknowledge the significance of placing a character as excluded as Zamzam at the center of this grand historical tale. There are those who think of history as the story of great men and women. There are those who insist that historical novels are best when the lead character is representative of the world depicted. Aboulela rejects those conventions and, instead, places at the center of her story a character who, given her gender, race, and social status as a slave is as marginal as it gets. In doing so, she provides a brilliantly intersectional perspective on the past, exposing the intertwined systems of power that aim to marginalize certain groups from historical narratives.

With this novel, Aboulela contributes to the growing collection of historical fiction by African women writers. History is one of the most potent forces in social life. Other novels tell the story of people living in the world. Historical fiction takes as its main concern stories about people changing the world. When women are made the face of events that change the world, it changes the way we think of women. We see them take the spotlight on the stage of world history. From that space, their humanity radiates because there is nothing more human than living in history and being a part of it.

It has been deeply gratifying to see more and more African women explore the genre of historical fiction. The body of work they have amassed is dazzling. In fact, I’d say that in the last 20 years, more African women than men have written most of the memorable historical fiction: Lalami’s A Moor’s Account, Makumbi’s Kintu, Tshuma’s House of Stone, Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun, Okparanta’s Under the Udala Tree, Mengiste’s Shadow King, Wayetu Moore’s She Would Be King, Gyasi’s Homegoing, Serpell’s Old Drift, Mohamed’s The Fortune Men, Petina Gappah’s Out of Darkness, Shining Light.

River Spirit doesn’t just join this illustrious ancestry. It shines in it. Aboulela has written a powerful political drama that blends Islamic faith, anti-colonial struggle, and a touch of romance.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions