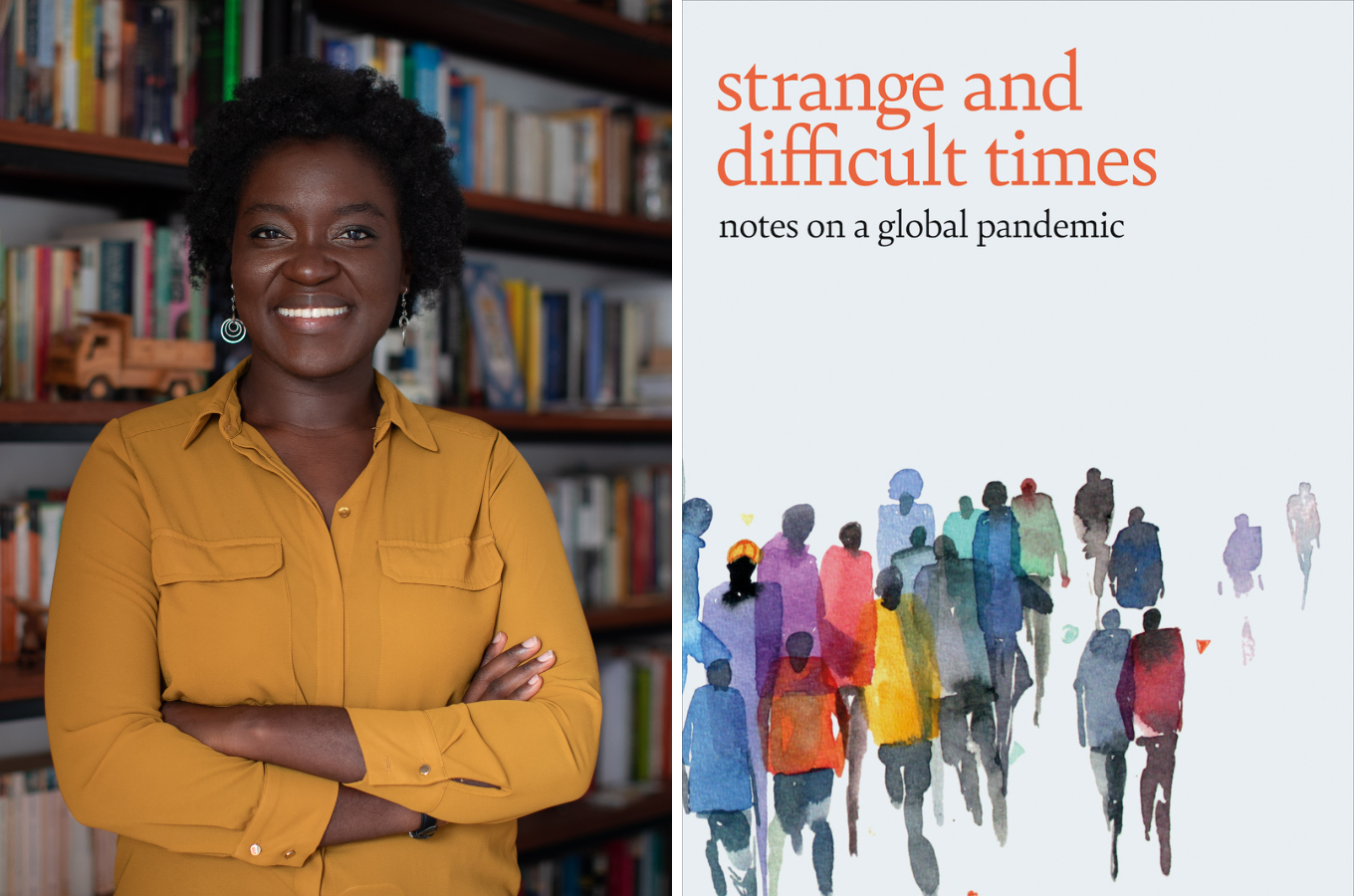

Nyabola is a well-known political analyst and activist with a J.D. from Harvard Law. She currently sits on the board of Amnesty International Kenya. Her writing covers a broad range of issues, including politics, technology, law, and feminism.

We recently read her new book Strange and Difficult Times: Notes on a Global Pandemic, published in February by Hurst. We loved the book for the ways it sharply examines the biases, assumptions and failures in Western responses to the COVID-19 pandemic, and touches on the ways in which the pandemic has exacerbated global inequalities. She also takes a historical look at pandemics in Africa, from HIV/AIDS in the 80s and 90s, Ebola in the 2010s, to Spanish flu a century ago, all the while emphasizing the need to archive how Africans experienced these global events and their aftermaths. Nyabola is a major voice, writing back against a structurally racist political and economic order through her own first-hand experiences of living within that system.

It was a joy to speak to her via email. In the interview, she shared with us some insights into the ways the pandemic as a problem of storytelling, how African communities came together to help each other during the crisis, and the importance of personal experience in social commentary.

***

Brittle Paper

Hello Nanjala. It’s great to chat with you. Congrats on the new book. Let us begin with you giving us a quick summary of what the book is about.

Nanjala Nyabola

Brittle Paper

You said in the foreword that this book is about telling the story about COVID-19 “properly.” What did you mean by that?

Nanjala Nyabola

Brittle Paper

I find the title Strange and Difficult Times interesting. Is there a story there?

Nanjala Nyabola

Brittle Paper

COVID-19 is still so fresh in the individual and collective consciousness. Like you note, there is so much about the pandemic that is still unresolved, including whether it has ended or is still ongoing. Did you worry that you were writing about something that was still too close, that people hadn’t acquired enough distance to really care about on an intellectual level?

Nanjala Nyabola

Brittle Paper

The world is not new to global pandemics. But are there aspects of this pandemic that are unprecedented?

Nanjala Nyabola

Brittle Paper

There was something you said in passing that left me really intrigued. You said you rode across Kenya on a motorcycle in the early days of the pandemic. That experience deserves its own book. Can you tell us about the experience?

Nanjala Nyabola

Brittle Paper

Would you say that your experience in being in Kenya through the thick of it and looking out from Kenya at the West and Asia and how they were scrambling gave you some unique insights into the pandemic?

Nanjala Nyabola

Brittle Paper

Let’s talk about the form of the book. You said that a book about the pandemic should be both a dirge and a sonnet. Can you elaborate on that fascinating note on genre? How would you describe Strange and Difficult Times in those terms?

Nanjala Nyabola

Brittle Paper

Still on the question of genre, what was it like crafting a social commentary woven with personal life and stories? What do you think this blending brings to the work?

Nanjala Nyabola

Brittle Paper

One of the strengths of this book is how self-conscious it is about language and reasoning. You spend a lot of time drilling through vocabulary, terminologies, rhetorical conventions like analogies, comparisons, and questioning. Why are you so attentive to language and the protocols of intellectual reasoning?

Nanjala Nyabola

Brittle Paper

Speaking of analogies, you kept going back to the colonial response to the Spanish Influenza with a focus on the vital stories that are missing about how Africans fared in those times in their private and communal worlds. Are there ways that the COVID-19 pandemic is reproducing its own kind of archival erasures?

Nanjala Nyabola

Brittle Paper

Being in the diaspora gives you a global perspective on blackness. What would you say the pandemic revealed about Black lives today?

Nanjala Nyabola

Am I in the diaspora?

Brittle Paper

I quite like ending with such a poignant question. It was great chatting with you, Nanjala. Thanks for your considered and illuminating responses.

***

Buy Strange and Difficult Times by Nanjala Nyabola: Amazon | Bookshop

Umar Jibril October 03, 2024 01:38

I enjoyed all the pieces and the intellectual vigour in which they were crafted.Above all,the urgency of the message portrayed is so palpaple and socially engaging .Fantastic pieces of prose.