Morakadu Moshitadi Lehlomela is a name I inherited from my paternal grandmother. She also had an English name, Betty, which I didn’t inherit. Her peers called her by the nickname Mpapailele and we the children called her Makgolo (meaning grandmother in Sepedi). Makgolo became my mother’s mother-in-law when my mother was a teenager. She didn’t particularly like my mother, but my grandmother didn’t like many people. I could count on one hand the number of people my grandmother liked and on that same hand, two fingers represented those she may have loved. It was hard to read Makgolo as she didn’t openly express any emotion other than anger, and maybe disgust.

As an adult, I have sat through conversations where people reminisce fondly about their relationships with their grandmothers.

They would speak with a spark in their eyes about their grandmothers’ recipes, stories their grandmothers told them, all the times their grandmothers stood up for them, and all the ways their grandmothers’ spoiled them. I have no such stories.

For as long as I could remember, my grandmother had wanted to die. She also didn’t shy away from telling us how she longed for death. When I was eighteen, my mother told us a story about my grandmother’s dance with death. She told us how as a newlywed and a new mother, my grandmother took a rope and headed for the shrouded hills surrounding our village, Mamone, to go hang herself. The story is that when one of the village women spotted her, the woman yelled for help – making a distinct noise known in the village as ‘Mokgoshi’. Mokgoshi is a specific sound made by a person in distress or danger to alert others of their situation. All our ears in Mamone had evolved to hear it and pick it up amongst noises of birds singing and even kids playing loudly.

Upon hearing the woman’s cries, members of the community came rushing and my grandmother was restrained and brought back home, to the very life she desperately wanted to escape. She didn’t receive any help or validation for her pain, instead she became the talk of Mamone and her husband who abused her mocked her for it. I concluded that this was what drove my grandmother to alcoholism and perhaps also transformed her grief into anger. My grandmother was a drunk for my entire childhood until she converted to Christianity in 2002, six years before her death.

There’s an ongoing inside joke in my family about my grandmother’s alcoholism that comes up whenever someone calls me Mpapailele. Mpapailele was my grandmother’s drunkard nickname. In Sepedi when you inherit your ancestor’s name, you inherit all their names, even silly names their friends gave them. When people do not call me Moshitadi or Morakadu, they jokingly call me ‘Mpapailele’.

My grandmother would get too drunk to walk. She would sway from left to right anchoring herself with the rocks and trees that covered our area until she could make it home. On nights when she was too drunk to make her way home, one of her drunk buddies who were as old as she was would ask us to fetch her because my grandmother was too heavy for them to carry. The teenagers and young adults in the family had the responsibility of heeding this call and bringing Makgolo home.

Now as adults, they reminisce about how heavy Makgolo was even in the wheelbarrow and how it didn’t help that we lived in a rocky mountainous place with no pavements or tar roads. Adding to the difficulty was that all this happened at night or early morning. In this struggle, my cousins and sometimes my brothers would hit a rock with the wheelbarrow or accidentally push it into a ditch and Makgolo would fall. She would mock them for being weak sissies failing to push a drunk old woman on a wheelbarrow, while singing songs that sounded like she was making them up on the spot.

Makgolo was an unconventional woman. When she was drunk, she would dance and sing loudly. Most of the lyrics to her songs were somewhat vulgar and often cryptic messages for someone with whom she was having issues. The vulgar lyrics weren’t a surprise to us because my grandmother was generally vulgar. If you misbehaved, my grandmother wouldn’t address what you had done, she would start mentioning your private parts while assigning odd or ugly attributes to them. She would then proceed to mention your parents’ private parts.

Her go-to insult for me was ‘red vagina’ because I’m light in complexion. Her nickname for me was ‘Nkhubedu’ which means ‘the red one’, so I suppose my vagina had to coincide with my overall ‘red’ complexion. Mentioning someone’s private parts in conflict is a big insult in Bapedi culture and it is even more scandalous to mention their parents’ private parts.

Makgolo didn’t drink any Western beers, only Mphohlomane, a Bapedi beer made from fermented sorghum that made her burp so loud that on the days she was not wheeled home, we could hear her burp and know she had arrived. Before westernisation reached the rural parts of Bapedi lands, Mphohlomane was the main beer Pedi people drank alongside another called Tho Tho Tho. Tho Tho Tho was a potent beer that caused neurological damage in those who consumed it and was eventually banned in the mid-90s. She also didn’t go to taverns or drink with anyone unless they were also a senior citizen. She knew all of Mamone and knew which house would have Mphohlomane and when. There were a few households where Mphohlomane was brewed for the purpose of selling.

Due to the tedious and meticulous processes involved in brewing and getting it ready for consumption, Mphohlomane wasn’t always available for sale. During these times my grandmother targeted the houses where there was a wedding or ancestral ceremony of sorts, as it was a custom to serve beer at these celebrations. She lived for alcohol and didn’t seem to care about anything else.

When my grandmother wasn’t drunk, she was distant, irritable, and all-around abusive. A pervasive sadness painted her face and would not leave her alone – that is until alcohol touched her lips.

My grandmother also had an irrational fear of lightning and snakes that seemed to disappear when she was drunk.

We lived in the mountains of Shuping (a section of Mamone) which my classmates jokingly called ‘The Kruger National Park’.

We had lots of snakes in the summer but despite living in this area for a long time my grandmother struggled to accept them as part of nature. She wouldn’t allow us to call a snake by its Sepedi name, noga. She called every snake, sebata, which translates to ‘the beast’. Whenever a storm would brew in the distance, my Makgolo would become panicky and search amongst the layers of cloths she wrapped around her waist every day.

***

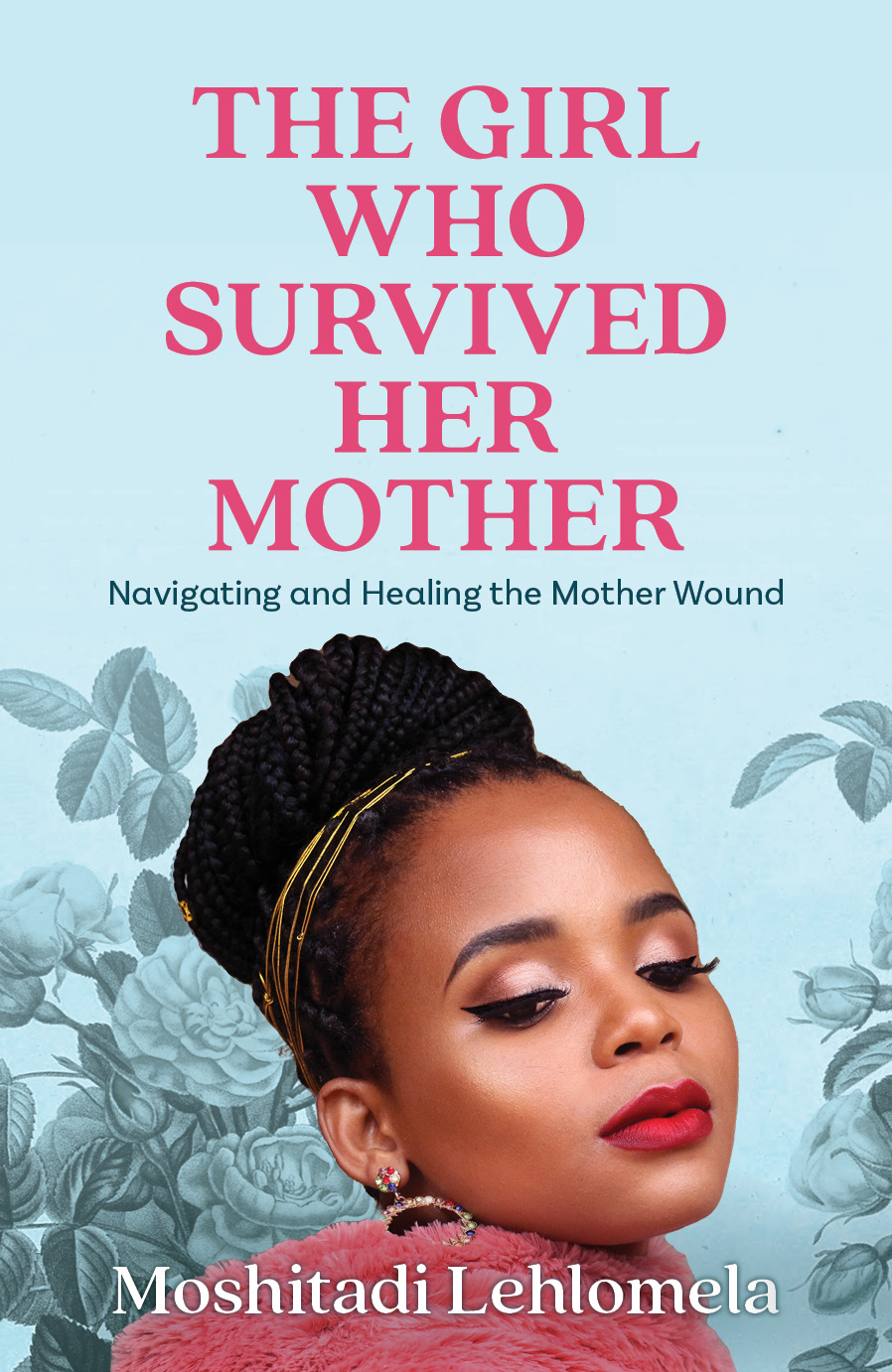

Buy The Girl Who Survived Her Mother here: NB Publishers | Barnes & Noble

Excerpt from THE GIRL WHO SURVIVED HER MOTHER published by Tafelberg, an imprint of NB Publishers. Copyright © 2023 by Moshitadi Lehlomela.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions