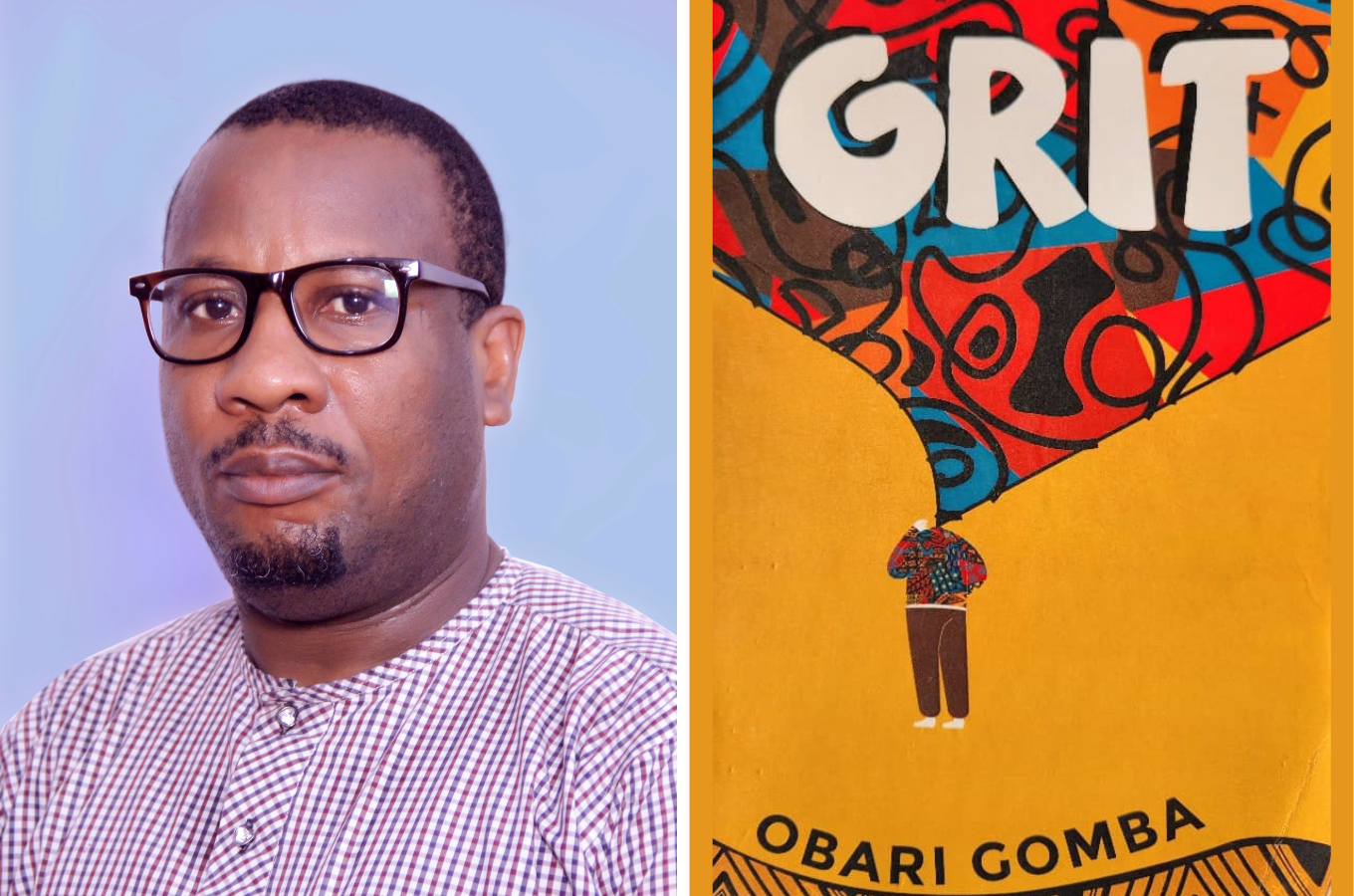

Obari Gomba’s Grit, published in 2023 by Hornbill House of Arts in Lagos, was recently shortlisted for the 2023 NLNG Nigeria Prize for Literature. In this interview, Darlington Chibueze Anuonye chats with Gomba on the inspiration and aspiration of his shortlisted play.

Set in the fictional town of Sonofa, the play dramatizes the Machiavellian politics that thrives in nations ruled by despots and depicts how such political intrigues penetrate the core of families and societies and destroy the unity of intention necessary for mass action. Beyond its engagement with the private and social lives of politically and economically endangered peoples, Grit offers a sobering and multilayered insight into the damaged psyche of war victims.

Gomba, a writer, scholar and educator, currently serves as the Associate Dean of Humanities at the University of Port Harcourt. He has received numerous awards, including the Association of Nigerian Authors Poetry (twice), Association of Nigerian Authors Drama Prize, and PAWA Prize for African Poetry. His other works, which span poetry and drama and all of which have been previously nominated for the Nigeria Prize for Literature, include: Length of Eyes, For Every Homeland, Guerrilla Post, and The Lilt of the Rebel.

***

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

Hi, Dr Gomba. Congratulations on your NLNG Nigeria Prize for Literature shortlist. Did the news surprise you, given the number of other great plays on the initial longlist? How does it feel to be so recognized?

Obari Gomba

Thank you for reaching out to me, Darlington. I believe the Nigeria Prize for Literature is a highly important cultural investment for all of us. We should celebrate the Nigeria LNG Limited for this investment that has the highest reward for literary creativity on the African continent. The least we can do as writers is to produce great works of literature and to compete for the prize. Each time I have competed for the prize, I approach it with cautious optimism. I compete in good faith, with the understanding that the jury’s decision is final and must be respected. That is why I have kept moving and I have been listed five times for this prize. No other writer has been that consistent, and no other person has been listed back-to-back twice. I am happy that I have been listed amongst the final three playwrights for 2023. A good play can be demanding on many levels. You work on it, and you convince yourself that you have written it to the best of your ability, and you hope that someone else will perceive that you have indeed written a good play. It happens often, perhaps as often as you can deceive yourself that you have produced a good play and as often as the reader can fail to understand the aesthetic merits of a good play.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

That’s true: Art is labour. Good art is good labour.

You directed the following comment to readers in The Playwright’s Note: “Grit is set in Sonofa, a fictional community. If the characters or actions resemble those that you know in real life, it is a coincidence and art does not apologise for its mimesis or verisimilitude.” I suppose that art is inspired by life, and should resemble that life in the most possible creative ways. Doesn’t Sonofa with its inchoate politics and incredible violence remind you of somewhere?

Obari Gomba

It is the nature of mimesis to remind us of “somewhere,” to remind us of many places and situations and persons. This play has resonated with a lot of readers because they see their social milieu in it. Nigeria’s politics comes alive in the experiences of the characters, but the play is not tied to a single locale. Sonofa can be anywhere and everywhere where politics is toxic, and communities are undermined by potentates. It is the ability of art to speak (to individuals and nations and eras at once) that secures the timelessness of art. I pray and hope that Grit will be with us for a long time, not as our reality, but as art that has power to evoke reality.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

Pa Nyimenu’s character, everything that he experienced, seems to point towards how deliberate the past is in haunting the present and the future. The political forces he challenged as an activist in his younger days were not just satisfied with murdering his wife, they also plotted to pitch his sons Oyesllo and Okote against each other, and ultimately destroyed them. There’s a sense in which it is appropriate to describe Oyesllo and Okote as victims who struggled against a darkness they did not fully know. But it appears that their temper equally contributed to their tragic fall. How central was hubris to their tragedy?

Obari Gomba

It takes a tragic flaw for a tragic play to earn its essence. There are blindspots in the lives of Oyesllo and Okote that are worsened by the hubris of their social engagement. They exemplify how a system becomes inescapable because it has the power to process both conformity and nonconformity or to set definite outcomes for those it chooses to destroy. Defeat is that default system, structured as a kind of political panopticon, regardless of the different temperaments of those brothers. The situation is quite familiar to us. Every human being is born into active or ongoing politics. The rest of our lives is our interaction with or escape from the politics of our social spaces. The features of our social spaces define our existence. For example, Oyesllo and Okote are born into a social context that has shaped their perception of life through abiding perils.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

“I once loved a good woman, but she was murdered. [There is silence.] I know what love is.” I’m wondering what this silence says about Pa Nyimenu, who must bear the pangs of such cruel history for the rest of his life.

Obari Gomba

That silence enables Pa Nyimenu and Okote to ponder the weight of their loss and to call on the audience to contemplate the unspeakable pain that time has not been able to erase. For individuals and communities, there is always the unsayable that words cannot capture, the silence that punctuates the best explication, the depth of human darkness that freezes utterance because it utters things that words cannot.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

Yes, I agree that silence sometimes carries the weight of anguish. This seems to explains Pa Nyimenu’s comment that “forgiveness is not amnesia. You can forgive a man who has injured you with a knife, but you will always be uncomfortable each time he carries a knife.” People and nations suffer constantly from the trauma of a past hurt. It’s difficult to heal after a war, it seems. Perhaps this reminds you of Nigeria, in any way. I suppose the wounds of the civil war have not healed well, and that is why during every election period, the skeleton of that war emerges. Doesn’t it surprise you how much fiction resembles life?

Obari Gomba

You know that literature does not exist in a vacuum. There is a two-way exchange between literature and society that allows the former to bear the burden of our collective memory. There are anxieties in a country like Nigeria where the nation-state dates to 1914; the political wounds are both obvious and recent. It has been the nature of politics to manipulate such wounds and to prevent healing. There are many knives that are raised and many reasons to be uncomfortable.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

Which was why Nmade distrusted Oyesllo’s alliance with the political party whose agents murdered his mother. “My husband is back from war, but he has remained in the mode of war.” That’s Nmade’s lamentation. It appears as if in nations ruled by despots and corrupt officers, the citizens are perpetually at war with the nation and with one another. Does a war end when the noise of battle is over? Or is it when the marginalized, impoverished and oppressed consider themselves represented, included and catered for in their government? That doesn’t happen in Grit. So, is war a continuum in a despotic nation?

Obari Gomba

War is always destructive. It creates traumas and post-traumatic stress in the polity. Oyesllo and Okote are victims of war. But it appears that it is the homefront, not the warfront, that troubles them the most. Men who have returned from war have to face a different kind of war in their homes because civil processes are full of treachery and eruptions. In a dysfunctional nation, there are tragedies everywhere, from the frontlines to the rearguard. Violence is constant, lethal in the hands of non-state actors who have been appropriated by those who have perpetually factored gore into enterprises of might. That is the kind of politics in Sonofa.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

Perhaps more than Okote, Nmade is the true victim of Oyesllo’s trauma and political ambition. His quest ruins their marriage, as he channels his negative energy, the residue of his frustrations, on her. And when we add this to the sad reality that Pa Nyimenu’s wife was murdered by his political enemies, the image before us becomes gloomier. Isn’t it possible that women are the real victims of war and history?

Obari Gomba

Women are victims of many of the atrocities in the world. Many perpetrators of violence see women as easy targets. As Opirate tells Okote in Grit, “evil picks on easy targets.” Nmade is a victim of her husband’s politics. And so are the women of Sonofa who are blindfolded and exploited by Matefi, their leader. Matefi is the opposite of Nmade. Matefi’s alliance with the political villains of Sonofa indicates that women can be complicit in the programmes of violence and can contribute to the destruction of their communities. This does not dismiss female victimhood, but it compels us to rethink it.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

I thought of Mafeti. Her role in the destruction of her community was so veiled in the outset that discovering her true allegiance in the end was an unsettling experience. But the relationship between Nmade and Bulu, Okote’s girlfriend, is really striking. Although their partners are enemies, these women go on to build a friendship that is unspoiled by the catastrophe happening around them. I think of this as the sisterhood ideology that Clenora Hudson-Weems articulated so beautifully. In her words: “This sisterly bond is a reciprocal one, one in which each [woman] gives and receives equally. In this community of women, all reach out in support of each other by looking out for one another. They are joined emotionally, as they embody emphatic understanding of each other’s shared experiences.” Were you thinking of this kind of feminist agency during the writing?

Obari Gomba

I was not thinking about feminism or any other theory when I was writing the play. I simply wanted realistic characters that would advance the plot. I wanted characters that would fit the context of the play because I saw my work as art, essentially. I knew that the work had to emerge as art first before it could speak to or about social issues. It is interesting that you have called attention to the depiction of gender, sisterhood, and feminist agency. All the women in the play are interesting characters. The women you have mentioned, Nmade and Bulu, are in love with troubled men; they know how to be in love and how to resist toxic masculinity at the same time. The decisions of the men impact the lives of the women. Bulu’s case is particularly interesting; she is unable to walk away, and she is also unable to accept matrimony. This kind of limbo has been caused by her love for Okote, but her perception of things is intact. It helps that she can bond with Nmade in a moment of difficulty and danger.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

Pa Nyimenu’s confession about the complicated relationship between duty and love is quite moving: “We disbanded the Grit Club, our small resistance group, when we began to raise families. We did not want our spouses and children to be caught in the crossfire of our activism.” This brings Okote and Bulu to mind. Their relationship was the one thing that helped stabilize Okote, at some points. What do we say of love in complicated times? “Love is the death of duty.” That’s what Maester Aemon said to Jon Snow in Game of Thrones. Snow himself had to convey the message to Daenerys Targaryen when it was necessary. What do we say of love and duty in a time that calls for grit?

Obari Gomba

Obari: That dilemma has been with us for ages. We are often forced to choose between duty to family and duty to the public. Too often, to choose one is to abandon the other, particularly in the context of activism or military service. The irony is that Pa Nyimenu and his allies disbanded the Grit Club to protect their families, but his family is stuck in danger, and he calls on his allies years later to perform the duty they had “abandoned.” It is like the irony of Bulu’s fear that Okote would die at war, but Okote faces greater danger at home than at the warfront. In all, the conflict between love (which is indeed a kind of duty) and duty (which is indeed a different kind of love) drives the characters towards a defeat of both love and duty. It reminds me of a statement in Ken Wiwa’s In the Shadow of a Saint: “Love is nothing until it has been tested by its own defeat.” This is most manifest in the lives of Pa Nyimenu, Nmade, and Bulu who reveal that Grit is a depiction of courage and brokenness.

Darlington Chibueze Anuonye

Darlington: “…a depiction of courage and brokenness,” that’s a wonderful way to say the unsayable. It’s been nice chatting with you, Dr Gomba.

Obari Gomba

The pleasure is all mine, Darlington.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions