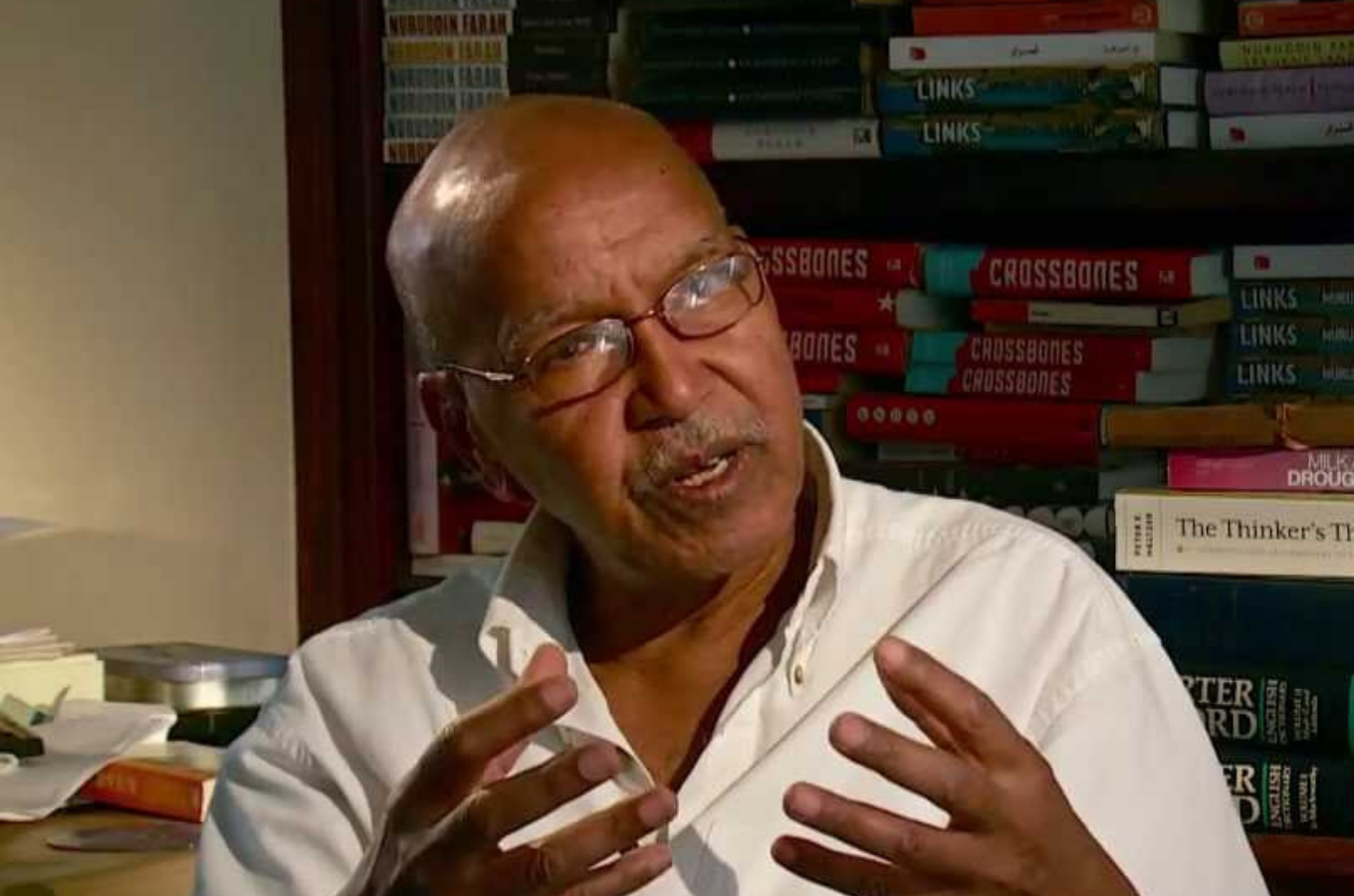

Somali author Nuruddin Farah recently sat down with Bhakti Shringarpure from Radical Books Collective and shared some fascinating stories from his life and career. We decided to share 5 interesting things we learned about Farah from his recent interview titled “Writing Somalia“.

Radical Books Collective creates an alternative, inclusive and non-commercial approach to books and reading. They organize virtual book clubs, book and author events and immersive seminars on foundational radical books.

Nuruddin Farah is a Somali novelist. He has won many awards including the Premio Cavour in Italy, the Kurt Tucholsky Prize in Germany, the Lettre Ulysses Award in Berlin, and in 1998, the prestigious Neustadt International Prize for Literature. In the same year, the French edition of his novel Gifts won the St Malo Literature Festival’s prize.

Here are 5 interesting things we learned about Farah from this interview

Farah’s Brother Greatly Influenced His Writing Career

Farah published his debut novel Crooked Rib (1970), when he was only 25 years old. It has been described as “one of the cornerstones of modern East African literature today”.

When asked how Farah got into writing in the first place, he remembered his brother fondly and his reward system during his childhood which would help Farah to direct his excess energy:

One of the first things I remember was reading Crime and Punishment in Arabic . . . I was about 10. I had an older brother who did not like that I was very very restless. Either I had a ball which I was kicking around and breaking glasses or I was moving around. So to make me calm down, one of the things he did was he would give me big books like Tolstoy’s War and Peace or Dostoevsky’s Crime and Punishment . . . The idea my brother had in his head was to give me the biggest book he could find so that I would sit down and the condition was that if I finished that book, came and told him the story of the book, he would give me a gift. That’s the way I earned my pocket money. That’s the way I earned gifts from him.

Young Farah was a Meddlesome Child

When Farah was 10 or 11, he started a letter-writing agency, which helped kickstart his literary writing career. The set of incidents that ended his agency and began his literary career is incredibly humorous:

I wrote letters for people who were old enough, as old as my father. They would tell me their stories and I would write letters in English or in Arabic and began earning money. One day, a man came to me and he said that he wanted me to write a letter to his wife. He was very angry with her because she went home and did not come back. . . In the letter, he said, “I want you to tell her to come back and I’m giving her time in which to come back. I want her back in three months. . .If she does not come back in three months,…I will go to Beledwayne, break every single bone of this woman and drag her all the way back to Kelafo.” I was about 10. Instead of writing what he told me, I wrote, “If you do not come back in three months, you may consider yourself divorced.

Farah’s little misinformation tactic leads to quite a lot of upheaval, however. When the wife received the letter, she took the letter to the judge of the town and explained that this is a letter written in Arabic. And the judge said that the letter would stand and if the husband does not come back in three months, then they may consider themselves to be divorced.

Farah added, “And lo and behold! Six months later, she got divorced, she married another man.” The man waited and waited, and when he came back to find the woman married, he asked her how “How come you married…I am your husband, what’s wrong with you?”

She showed him the letter that Farah wrote. The now ex-husband spoke to Farah’s father, who forbade him from writing letters thereafter. Farah added with a laugh, “Now I’ve run out of pocket money. In order to continue receiving pocket money, I thought I would continue writing. That’s one way of looking at it.”

Farah Chose to Study in India over America

Farah was 20 or 21 when he arrived in India. From 1966 to 1970, he pursued a degree in philosophy, literature and sociology at Panjab University in Chandigarh, India. However, Farah’s decision to go to India was a tough one, where he gave up a scholarship to a prestigious university in America (none other than the University of Wisconsin–Madison):

Many people who knew me at that time did not think that it was wise of me to go to India and nearly everyone including my older brothers thought that I would benefit from going to America to study journalism and literature because I had a scholarship to go to the University of Wisconsin-Madison. I did not like going to America and I’ll explain to you a very silly couple of silly incidents that happened in Somalia at that time

Some Somalis had gone to America and Italy and Germany because there was no University at the time in the country and they came back and like in the days of COVID, they used to carry small little bottles full of alcohol and therefore every time they shook hands with people in Mogadishu, they would clean their hands and say “germs germs” because they came from Europe or America. The idea of carrying a small bottle full of alcohol and cleaning my hands with alcohol every time I greeted the Somali okay made me feel very silly and I thought if I go to India, nearly everything is germ-full. If I survive the germs in India, I would have a great immunity system which I still do.

Farah Has a Thick Skin When it Comes to Racism

When asked about his experiences with racism in India, Farah was surprisingly positive and said he did not really feel hurt only because he had grown up with the belief that Somali peoples were the most beautiful, intelligent, and driven:

Honestly, I don’t succumb to racism. I can understand somebody disliking me for some reason or another but somebody playing racist games with me it doesn’t make sense because I told you, you know, from a small age I was told you’re the greatest . . .which means “there is no one better than you”. Every mother you know Somali words of endearment are the most beautiful words of endearment and yet Somali also have a very very sharp tongue and so they could go either way from one second to the other. The mother who is saying to her child my sweetest child next time she could say you are the stupidest idiot that God has created, so you know we survived all this and to survive that and then go to India and then survive the germs.

Why Does Farah Always Write About Somalia?

Since leaving Somalia in the 1970s he has lived and taught in numerous countries, including the United States, Britain, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Sudan, India, Uganda, Nigeria and South Africa. In fact, he has not lived in Somali for close to 50 years.

Why then does Farah continue writing about Somalia and not any other locale? He has 4 scintillating reasons for doing so. Read on to find out:

Every time I have set the story somewhere else, often I remind myself the fact that although I have now lived in Cape Town for 25 years, I tell myself everything that I know about South Africa could be put on the back of a postcard. In other words, very little. This is not the case but that’s the way my starting point is. I need to know a lot more than I already know before I write about it.

The second thing that’s also very very important to remember is that people take ownership of the country from which they come from and therefore even if you have not made a mistake by writing about somebody else. Let’s say you write a beautiful article, you misspell the name of someone. You misspell the name in such a way that it gives a different meaning to the name. Somalis who read the article would look at it and say “What does he know? He doesn’t even know the difference between Baarr and Bar.” You see because one of them has double R double A and the other one has one A and so on and so forth. So one has to be very cognizant of the fact that you can’t get away with mistakes. You could have a beautiful book, you make one little mistake and the local person – the Norwegian, the Danish, the whoever you’ve written about – would say the most terrible things about that book because they found one mistake. If ordinary people find one mistake, you’re in a terrible situation. If scholars find one mistake in your book, they turn it into a PhD. So you have to continue thinking about all this.

The other thing obviously is the ownership is quite important. Now I am a Somali. It’s possible that I may not have lived in Somalia for close to 50 years. I continue writing about it. Why? Because I know that even if I make a mistake, my mistake would be an honest mistake and even if I make a mistake, a Somali in his or her right senses would not say, “This person doesn’t know Somali.” They could probably say “This person doesn’t have the anthropology of that particular thing.” You know in 2011 a kilo of sugar didn’t cost $5, it cost $2. Somebody could argue about that but when I write about sugar and the cost of sugar I would not identify how much. I could say the sugar was cheap or sugar was expensive. That way, you can avoid somebody attacking you anthropologically and saying this.

One of the other reasons is Somalia is an open field. There aren’t many writers, hiding in trees, doing all kinds of other things and therefore that’s what I do. Somalis also because they like certain books and they hate certain books and they tell me why they hate certain books. Somalis don’t like you to talk about sex. They do it all the time, but they don’t like you to talk about it.

Farah’s interview reveals a lot more interesting secrets about his life and career. We highly recommend you watch the 1-hour long interview if you have some downtime.

Check it out below:

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions