He came late to pick me up at JFK airport, my father. In 2005, after the terror of 9/11, parents were pretty scared to let their children fly by themselves under the care of the airline – except Mama, of course! I had been on two connecting flights from Bulawayo, first at O. R. Tambo in Jo’burg, where I’d wandered off and the plane had almost left me, and then at Gatwick in London, where the British Airways stewardess in whose care I’d been put dumped me in a room full of candy, where I did what any sensible eleven-year-old would do and stuffed myself silly, crunching through M&Ms and Oreos and Cadbury chocolates and Belgian creams like a Pac-Man on steroids.

And then we were gliding over New York City, and I felt the thrill of being an astral thing. I tried to make out the Big Dipper or the Little Dipper in the early morning darkness as we descended into JFK, but the stars were outdone by the skyglow of man-made constellations winking up at us like cyborg kin from the cosmos below.

The next moment, I was on solid ground, my sneakers squeaking across dull parquet floors, blinking back tears under the blunt lights of the airport, my father nowhere to be seen. I must have felt the abysmal terror of being without him even then, unable to locate his face. It was a wondrous thing, that face, a solid, pecan vista on which I could trace my own button nose, with its fleshy alae, and plump lips that, when he smiled, revealed, just as my own did, a constellation of pearly teeth dipping into a galaxy of wine-dark gums.

I looked up at the dour-faced airport officer in whose care I’d been put, and then bent over and vomited a sludge of candy right onto his polished shoes.

He leapt back, his lips upended in dismay. “Why, you lil n- ”

And then, there he was, ambling down the airport corridor in black jeans and a tan leather jacket, the gold rims of his oval specs catching the light. I fluttered my eyes at him. I had not expected to feel so shy. He seemed impossibly tall, his gangly legs launching him in lofty strides. I remained standing beside the angry officer, next to a dark curio store with feather headdresses and wooden Indian dolls pressed against the glass, watching first his face and then his approaching feet.

“Hello, missy,” he said in English.

Hello, missy.

I smiled through my tears. We had always used English together, he and I.

He gave my cheek a gentle tug. And then he frowned. “What’s the matter?”

The officer, who had quietened down, began to speak real fast and aggressive again, gesticulating at me and then at the gooey mess at his feet. My father, too, began to speak, his voice rising to a dangerous pitch as he yelled, “She’s just a child, a child!”

I beamed, basking in his celestial warmth. He turned to walk away, and I followed him, slipping my hand in his. Together we were swept up by the sea of airport strangers, the surly officer rapidly fading into an insignificant spec.

It was the first time it was just the two of us, together like that. I could not remember when he had last visited home. We wrote each other often; he had started writing me letters from the time I could read and write, sharing stories from his childhood, which sounded like fables, for I could not imagine him, this colossal, hopelessly cosmopolitan man, now a professor of astronomy, as a half-naked rascal once-upon-a-time slinking away from the evening fire in his father’s homestead to crouch behind the cattle kraal and study the night sky.

There he would remain for hours, the garlicky scent of aloe vera filling his nostrils, the cicadas a resounding orchestra, somewhere in that blue-blackness the click-click of the bats, and above all this, a glittery panorama stretching in all directions, kissing the heavens and the earth, with the umThala, the Milky Way, arching across the sky like the patch of hair left on an infant’s head after the rest has been rubbed off.

Here, his sentences would become loopy and self-indulgent. I would read in one long exhalation, gasping for breath, about the marvel of isiLimela, the Digging Stars, Pleiades, the first of which winked in the eastern night sky in September, hot-blue fireflies heralding the spring rains. My father would track them, crouching with his lanky, eight-year-old body held taut, trembling, emitting a sigh when he was finally able to pin-point a shimmering light one night, and then two the next, and then four, and so on, until six, sometimes seven glow-worms hovered overhead, webbing the obsidian sky with their blue, gossamer light.

Then he got a scholarship to attend the village school run by the Catholic missionaries and stopped rising with the Digging Stars to latch a pair of oxen to the plough, catching the last of them disappearing in the western skies as he and his siblings trudged barefoot across the crumbly soil headed for the fields, the star so crisp and hot-blue he would instinctively stretch out a gangly arm as though to pluck it. Instead, he began to rise to the regiments of an alarm clock, a red, plastic, screeching thing gifted him by Father Pius.

Years later, as an adult, while trudging through a snowstorm in downtown Manhattan, or just after one of his lectures to a stuffy room full of ambivalent freshmen, or entombed in the gloomy subway, he would look about, dazed, as though he expected to find himself out in the Sahara bush under the infinite expanse of a bespangled night sky. He would jerk up, startled to find himself where he was, a smothering weight crushing his chest. Once, he whispered, “What am I doing here?” and a scraggly homeless man yelled back, “Why don’t you go back to Africa!” This rejoinder was so unexpected, so strangely percipient, that he burst out laughing. The homeless man, too, began to laugh. They laughed together, like that, for a good, long minute.

I did not know what to make of this. I was too young for nostalgia. Why did he share these stories with me? He must have known I would not understand them. I would frown and frown at his perplexing letters, flattered by his adult attention, my head throbbing not with the dawn of understanding but a foggy migraine.

Now, stumbling to keep up with his long strides as we made our way through that monstrosity of an airport, I felt stiff. There was a clumsiness to our bodies. He kept yanking my small hand encased in his large, sweaty palm, lurching me forward, straining to look behind us, ahead of us, all around us, his eyes flitting from side to side. Finally, he hailed a cab.

“How was your flight?” he said, easing me into the backseat.

“It was nice,” I said, my voice hiccupping as the cab lurched forward.

“You didn’t get lost?” He looked out the window, scouting the crowds etched in oblique shadows by the dawn light.

“Hmm-hmm.”

“Tired?” He looked over his shoulder out the window at the back.

“Hmm-hmm.”

We were quiet for a while as the cab nosed out of JFK. We spent a good thirty minutes in that chaotic airport jam, my father tense beside me, squinting out the windows. Then the cab eased onto the freeway and his body loosened, and the air lightened between us.

“Your mother has been calling and calling,” he said, ruffling my braids. “She thought they would forget you in London.”

I chuckled.

***

Read full excerpt here: Google Books

Buy here: Amazon

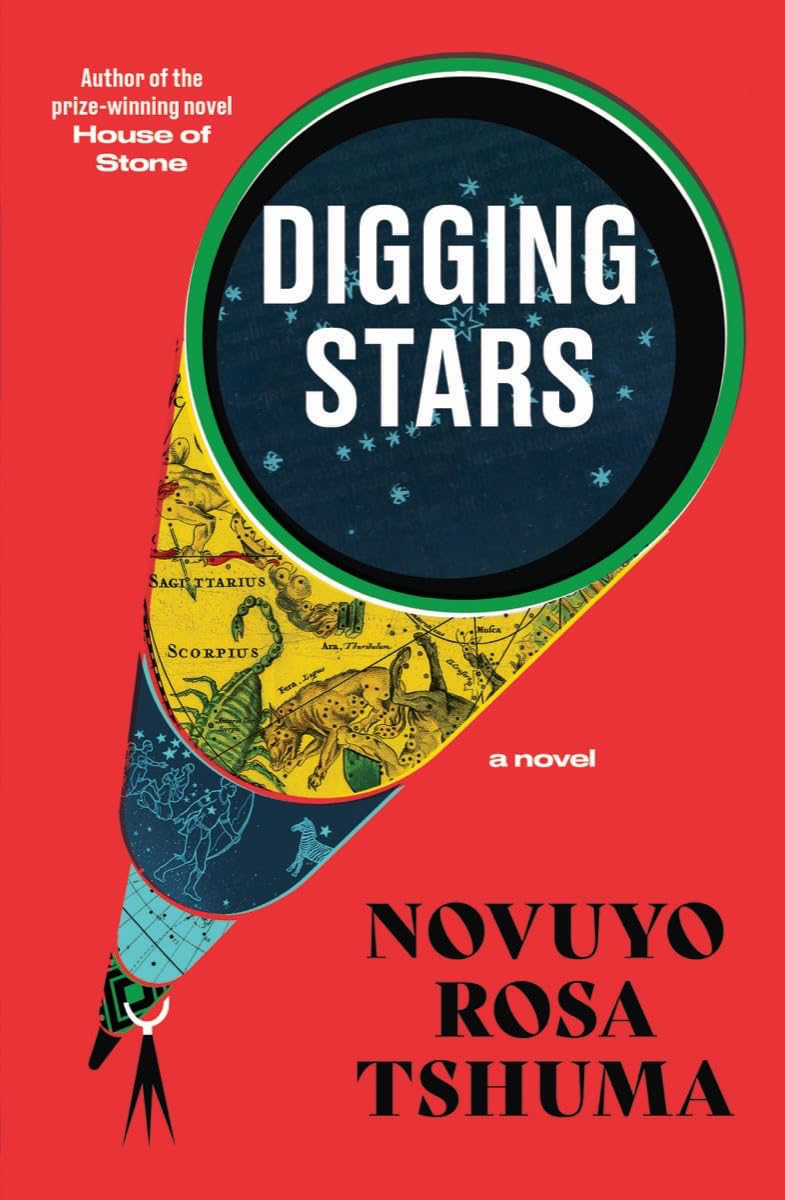

Excerpt from DIGGING STARS published by W. W. Norton & Company. Copyright © 2023 by Novuyo Rosa Tshuma.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions