I’m interested in Coetzee above all as a South African writer – yes, still. To many people, including Coetzee himself, this has been far from the ideal way into his work. The reasons for this are familiar, at this point even rote: writers from Africa, perhaps especially from South Africa in the decades when Coetzee began his career, tend to be held to a higher standard of political engagement and social representativeness than writers from elsewhere. Many of the most ethically charged places in Coetzee’s work dramatize this predicament in direct and oblique ways. The most famous of these is probably the scene in Disgrace when David Lurie refuses to apologize for his affair with a student in the terms demanded of him – a curt nod to South Africa’s Truth and Reconciliation Commission. Like many of you, I suspect, I was once utterly enamored with that Coetzee: the one who, pinned to the wall, waxed tender about dogs, who insisted on writing out answers rather than speak extempore in interviews. I have on many occasions joined in the critical indictment of how writers from Africa are read in and by the so-called West, and celebrated abstract or indirect ways of engaging with African realities.

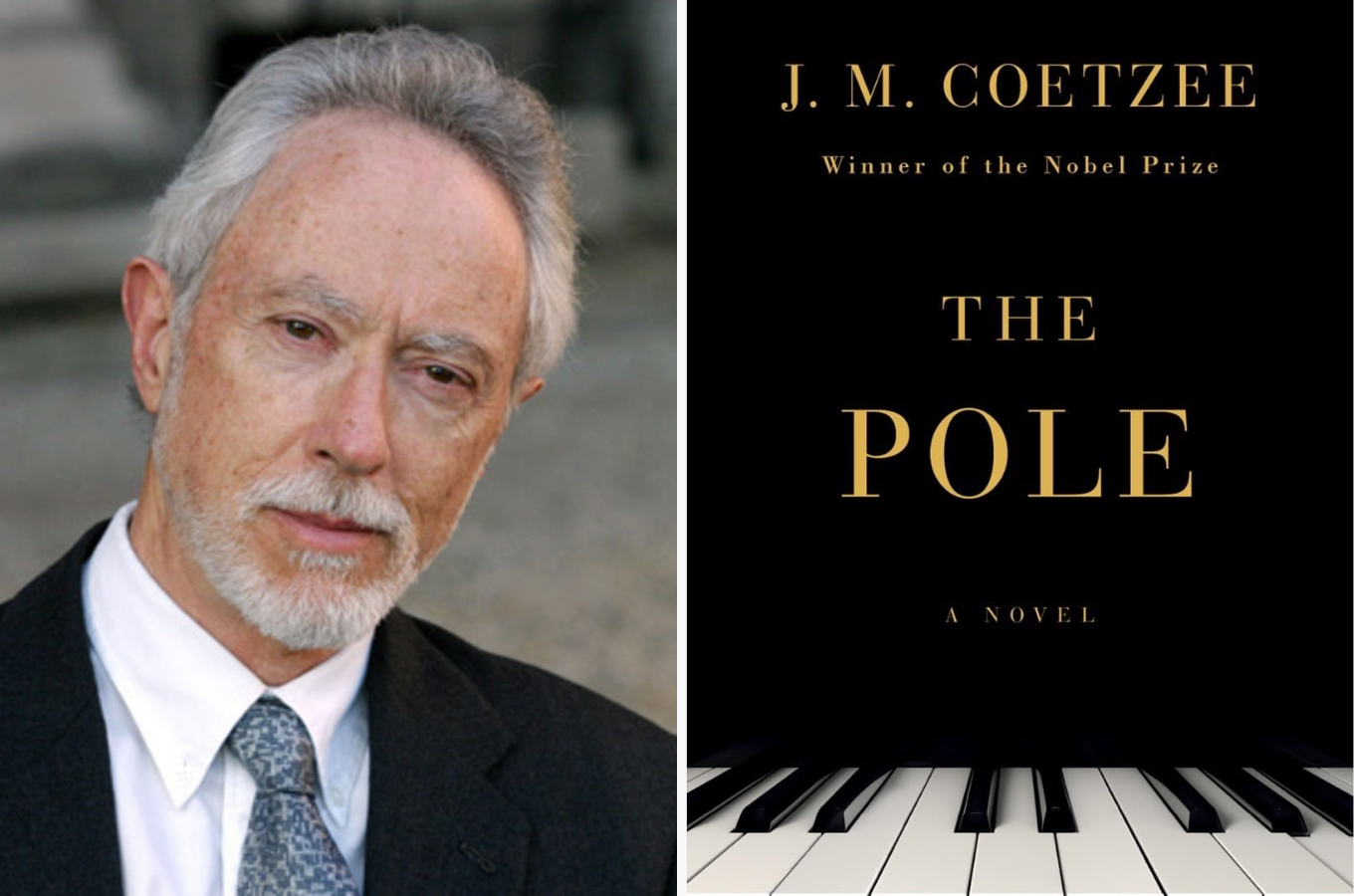

Unfortunately, The Pole left me more than anything with a clearer understanding of what Coetzee has turned away from, which is, in a word, place. All the other hallmarks of his style are still there, to the extent that reading this latest felt to me a bit like an elevated version of MadLibs. Bits and pieces of other books and eras kept popping up: the title character’s fixation on Dante and Beatrice made me flash back to David Lurie’s unwritten opera about Byron and Teresa; ruminations on Polishness (and briefly, Russianness) recalled through-lines about national character in Diary of a Bad Year, as did the cryptic section numbering; the lackluster old-man sex felt “sourced” from half a dozen Coetzean predecessors. There are, I’m sure, dozens of academic essays waiting in the wings on Coetzee’s meta-self-criticism via Beatriz’s description of Wittold’s musical style and its parallel with his expressions of eros, one of Coetzee’s favorite words. Recalling his self-assessment via alter ego in Summertime – “Too cool, too neat,” with “the control of the elements too tight” – we might see Coetzee’s almost, sort-of projection of himself onto a Polish pianist as a final come-down from the Dostoevskian Coetzee of yore. I am well aware that this distillation of elements is often a defining trait of writers’ “late style,” and I can imagine teaching The Pole alongside, say, McEwan’s On Chesil Beach or Barnes’ The Sense of an Ending. Hell, we might as well throw in Elizabeth Finch.

I would be happy just to go with this synchronic positioning of “the late Coetzee,” which is not the same as saying that I find it interesting, if I didn’t miss what he’s jettisoned so much. The philosophical and libidinal themes that run through the whole of his output feel easy to me, in their performance of “difficulty,” without the stakes that place once anchored them to, even when “place” was presented as a straight jacket. The Coetzee scenes that have stuck with me over the years are muddied by South Africa, quite literally: Michael K burrowing into his pumpkin patch; the Coetzee of Boyhood letting his black childhood playmate take the blame for a mess he’d made, knowing how brutal the punishment would be; Mrs. Curren driving recklessly into a township conflagration in Age of Iron. Obviously, Coetzee has always written meta-fiction, and he’s always used allegory to baffle an unchecked hunger for visceral response. For better or worse, the spare obscurity of The Pole has been his calling card for a long time. But at his best, even in his post-South African years, he has also excelled at showing what it is to try to do philosophy at the limits of its capacity to facilitate anything like a good life. That, for me, is (was) the sweet spot of Coetzee’s oeuvre: the point where abstraction gives the lie to itself and yet somehow feels more essential for it. The Pole, no doubt by design, has nothing of the genius loci that makes that possible. It is Coetzee as shtick.

***

Buy The Pole by J.M. Coetzee: Amazon

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions