Introduction

Afrofuturism and Africanfuturism: Same Difference?

With the release of the film Black Panther (2018), Afrofuturism became a buzzword in the United States. The movie features the fictional African country of Wakanda, a nation replete with technological innovation in which Blacks thrived and had never been subjected to European colonization. The film is conceptually and visually remarkable. Its African-themed setting, otherworldly design, and superhuman characters suggest that the label Afrofuturism was all but self explanatory for mainstream theatergoers. The first time much of the American public had ever heard the term was in relation to the film and suddenly it seemed as if it was everywhere. Those who are familiar with the etymology of Afrofuturism, however, know that it is a decades-old international academic area of inquiry with wide-ranging social, methodological, and economic implications.

The term Afrofuturism was coined by American author and cultural critic Mark Dery in his 1993 seminal essay on science fiction literature, “Black to the Future,” which included an interview with African American writers Samuel R. Delany, Greg Tate, and Tricia Rose. Dery wondered why there weren’t more African American science fiction authors, since this genre’s frequent inclusion of unfamiliar species and encounters with foreigners would likely resonate with a population that, itself, had long been viewed and treated as “other” by much of White America. Similarly, because science fiction was considered a lesser category in the hierarchy of Western literature, it made it an especially fitting form of expression. In Dery’s mind, African American writers were uniquely suited to craft narratives about the future that reflected a Black point of view. This aspect would distinguish their stories from those produced by White male writers, who not only dominated the field of science fiction but also tended to feature White male characters.

In an attempt to name a subgenre of science fiction writing, Dery tentatively defined Afrofuturism as speculative fiction that displayed the following traits: “treats African-American themes and addresses African-American concerns in the context of 20th century technoculture—and, more generally, African-American signification that appropriates images of technology and a prosthetically enhanced future.” By the time Black Panther was released twenty-five years later, studies and discussions of Afrofuturism had grown to encompass African American production from different disciplines and time periods. Scholars had also broadened their geographic scope to identify examples deriving from multiple sites across the diaspora, as well as from the African continent.

While many intellectuals in the United States now include African speculative expression in their examinations of a wider body of Afrofuturism, a growing number of Africans and Africanists have voiced concerns about this approach. They do not take issue with the concept of Afrofuturism in the US context but rather with extending the Afrofuturist label to African creative work without distinction. Some Africans and Africanists have pointed out that this tendency glosses over cultural, environmental, and racial factors relevant to the African work; fails to take into account that Afrofuturism centers the Western imagination and gaze; and frames its discourse on US-originated and US-oriented terminology. In light of what they believe are Afrofuturism’s limitations, Africans and Africanists have emphasized a need for dedicated consideration and analysis of African production. This publication is an introductory study of Africanfuturism—a body of African speculative expression that is distinguishable from, albeit unquestionably related to, Afrofuturism with its roots in the United States.

The Development of Discourse on Afrofuturism in the United States and its Expanding Scope

Soon after Dery’s essay was published, academics from a variety of fields began to investigate and discern what might be considered Afrofuturist production, as well as expound on Afrofuturism’s meaning. In 1998, while still a doctoral student at New York University, sociologist Alondra Nelson started the AfroFuturism listserv (www.Afrofuturism.net) to explore futurist themes and technological innovation in Black cultural production. In 2000 she authored the article “AfroFuturism: Past-Future Vision” for the (then print) magazine Colorlines, in which she asserted, “AfroFuturism has emerged as a term of convenience to describe the analysis, criticism, and cultural production that addresses the intersections between race and technology. Neither a mantra nor a movement, AfroFuturism is a critical perspective that opens up inquiry into the many overlaps between technoculture and black diasporic histories.”

Some of the topics discussed on the listserv were developed into academic essays that appeared in a special issue on Afrofuturism of the journal Social Text (2002), organized by Nelson. In the issue’s introduction, she states that Afrofuturism “can be broadly defined as ‘African American voices’ with ‘other stories to tell about culture, technology and things to come.’” Nelson’s essays for Colorlines and Social Text constitute some of the earliest examples of an individual offering their own interpretation of Afrofuturism in a more formalized and permanent scholarly format.

A few additional articulations give a sense of how other academics have approached Afrofuturism. American-studies scholar Ruth Mayer explored diasporic creatives’ use of Middle Passage imagery and the contemporary experiences of displacement and migration within and beyond the genre of science fiction in her article “‘Africa as an Alien Future’: The Middle Passage, Afrofuturism, and Postcolonial Waterworlds” (2000). In her essay, Mayer loosely defines Afrofuturism as “an artistic and theoretical movement which has become a vital part of contemporary black diasporic (pop) culture.” In her article “An Afrofuturist Reading of Ralph Ellison’s Invisible Man” (2005), literary science fiction specialist Lisa Yaszek identifies Afrofuturism as an “international aesthetic movement concerned with the relations of science, technology, and race [that] appropriates the narrative techniques of science fiction to put a black face on the future.” Art historian Jared Richardson explores Black women artists’ utilization of the abject Black female body in his article “Attack of the Boogeywoman: Visualizing Black Women’s Grotesquerie in Afrofuturism” (2012). According to Richardson, “Afrofuturism offers a racialized science fiction that reimagines black temporality vis-àvis technology, galactic elsewheres, disjunctive time, and speculative narratives stemming from either utopic or antithetical visions.”6 Lastly, in her book Afrofuturism: The World of Black Sci-Fi and Fantasy Culture (2013) author and filmmaker Ytasha Womack states, “Both an artistic aesthetic and a framework for critical theory, Afrofuturism combines elements of science fiction, historical fiction, speculative fiction, fantasy, Afrocentricity, and magic realism with non-Western beliefs.”

These examples demonstrate how the American scholarly community has continued to reinforce and expand Dery’s concept of Afrofuturism in the years since he coined the term. As such, there is no definitive definition, and the term remains open to interpretation. However, intellectuals are generally in agreement on two points: first, that 1993 can be understood as the origin date for the term though not the beginning of Afrofuturist expression itself; and second, although Dery should be given credit for coining the word, African American creatives should also be recognized as progenitors of what would later be called Afrofuturism.

The scope of Western scholarly explorations of Afrofuturism has also been flexible, growing from exclusively African American works to those by African creatives active within and outside the United States by the early twenty-first century. This development was part of the investigation of a “second wave” of Afrofuturist expression that followed the “first wave” of the decades 1960s–80s and which included such works as the music of Sun Ra and Parliament Funkadelic, the writing of Octavia E. Butler and Samuel R. Delany, and the films Space Is the Place and Brother from Another Planet. Illustrations of Nigerian-born and United States–based artist Fatimah Tuggar’s digital photomontages from the mid to late 1990s, for example, appeared in Nelson’s Afrofuturist issue of Social Text. Yaszek (2013) identified a strain of “Global Afrofuturism” that had started to develop in the 1980s outside the United States. Those creatives, like their American colleagues, published with Western magazines and presses, and participated in networks of exchange and collaboration with online venues. Authors Bill Campbell and Edward Austin Hall included science fiction–themed stories by Africana writers in their edited volume Mothership: Tales from Afrofuturism and Beyond (2013). That same year, Naima J. Keith and Zoé Whitley curated the international, interdisciplinary exhibition The Shadows Took Shape at the Studio Museum in Harlem, which included African production. In their 2016 edited volume, communications studies and Afrofuturism expert Reynaldo Anderson and Africana studies scholar Charles E. Jones articulated a shift in emphasis from the West to a more Pan-African scope of production as a defining characteristic of “Afrofuturism 2.0.” Across disciplines, Americans were including African creative expression in their Western-originated and Westernorganized Afrofuturist projects.

***

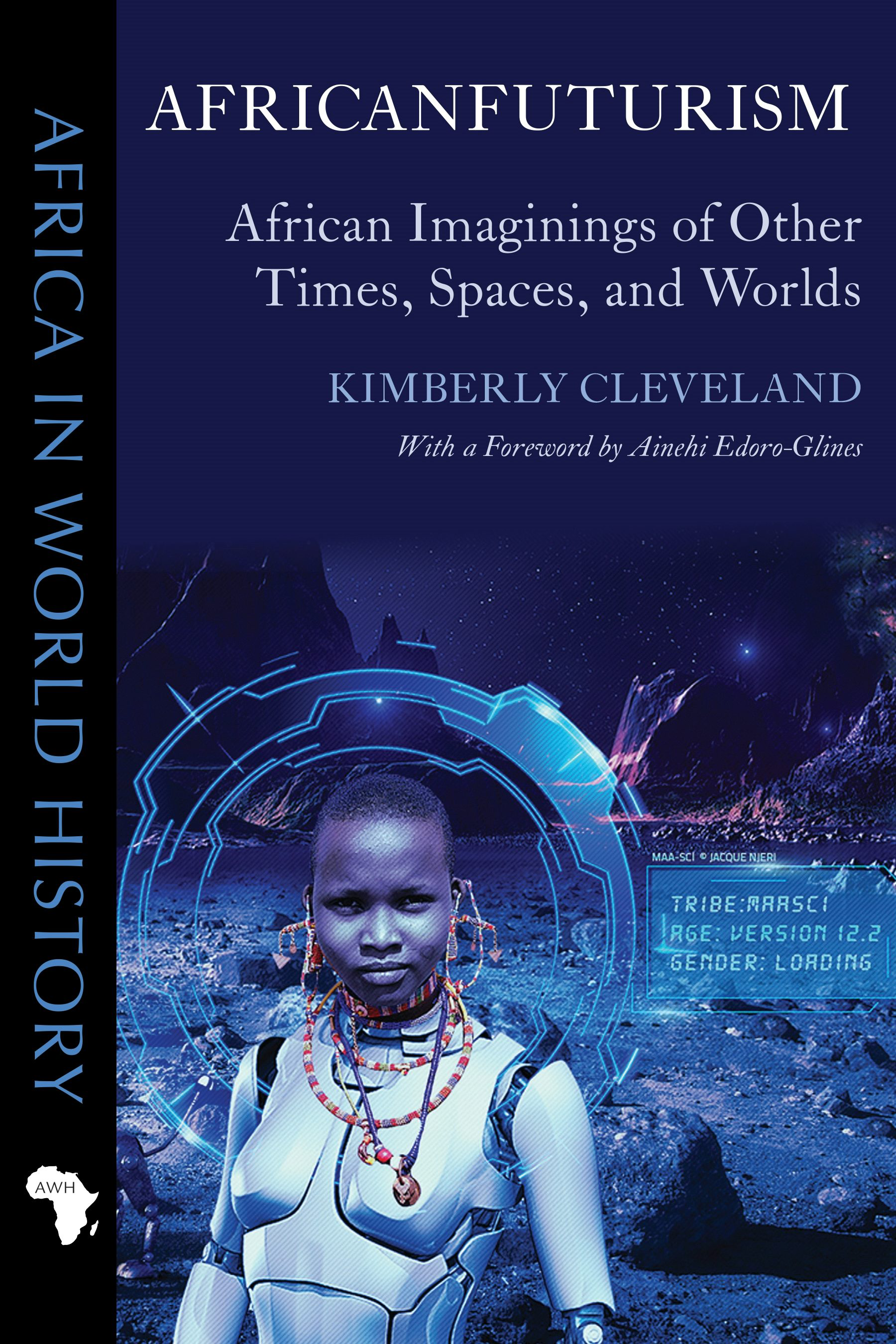

Buy Africanfuturism here: Ohio University Press

Excerpt from AFRICANFUTURISM: AFRICAN IMAGININGS OF OTHER TIMES, SPACES, AND WORLDS published by Ohio University Press. Copyright © 2024 by Kimberly Cleveland.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions