Onheil Manor. Lysbeth takes in the tableau in front of her. Blankets of white linen hide what appears to be a jumble of furniture. Her eyes land on the many iron sconces festooned onto the wooden walls of the grand room. She is a lover of details, and her curiosity is always searching for the hidden clues. The wall sconces are perfectly aligned as if someone had done the exact measurements. She peers at the wall with a judgmental squint.

This was done for the beauty of the look, by an incorrigible aesthete, because no one sane would kindle that many lights in an all-wood house.

In their rusted condition, the sconces appear out of place, as if they belong to an ancient place, way back in time. She glances at the floor. The wooden planks are buffed smooth and flat with a fresh earth color that could only have come from decades of many feet walking over it. Lysbeth finally snaps out of her reverie. She turns to the woman in black, but the lady has vanished. She is not there.

“Madame?”

Lysbeth spins around and calls again.

“Are you there, madame?”

But no one answers.

“Anyone?”

There is a whitewashed door on the far opposite end of the hall. The grand room suddenly feels much bigger than a moment ago; as if a cornfield came to stretch itself wide open inside the belly of the manor. Lysbeth hears a gust of wind blow, but none of the windows are open. Her eyes jump to each windowpane just to be sure. The temperature drops to a chill. She pulls her black bear fur coat closer to her body. Her love for this fur coat borders on obsession. It has kept her alive during many winter seasons when Arctic winds and heavy snow killed full grown men for free. It had been too big for her as a child. But her woman’s body now fits the coat to perfection. Her old memories start to play in her mind’s eye. Lysbeth remembers the man who saved her life. The coat was a birthday present from Vincenzo di Parma. To secure it for Lysbeth, Vincenzo bartered with an Indian fur trader from the Poconos. In return, he gave the fellow a Spanish rapier sword. Vincenzo took a paternal liking to the young African girl who served him his rum. Her bird-thin wrists and alarming clavicles touched his jaded heart. Saint Vincenzo. The Venetian was a talented criminal and a boastful buccaneer. He robbed and raided Spanish ships up and down the Caribbean waters. When he met Lysbeth, he was convalescing in New Sweden, where no single soul along the banks of the Delaware River had prior knowledge of his crimes. Vincenzo became a regular at De Geer’s Huis the year Lysbeth arrived from New Netherland as a 13-year-old orphan. The conditions of her guardianship meant five years of indentured service under Marianne de Geer. It meant hard work as a tavern waitress, six days a week.

***

Vincenzo often became philosophical after several rounds of rum. He would huddle close to Lysbeth and tell her, “No Spaniard is a victim, my dear child. Everything I partook, they had stolen first. I would rob them 100 times over and sleep like a babe in me mama’s arms.”

Vincenzo’s gracious gift is keeping Lysbeth warm as she stands in this majestic manor where the air has turned ice cold without warning. Lysbeth referees an internal debate with herself.

Shall I go to that white door and knock on it? Or must I leave well enough alone? Santo António, have mercy.

Lysbeth has questions for the old woman. Pointing and disappearing like that was weird, if not rude. But in the end, her African common sense prevails. Lysbeth takes a deep breath and starts up the staircase.

***

It is a beautiful staircase; an expensive-looking creation of carved mahogany with a lustrous sheen. Someone must have polished it earlier that morning with wax and oil. Lysbeth wonders how a staircase fit for a king could have found its way to the backwoods of Sleepy Hollow. Onheil Manor is a miniature palace in comparison to what passes for architecture in the Upper Hudson Valley. Most of the farmhouses, cottages, log cabins, and barns in Sleepy Hollow, and its surrounding settlements, have a primitive simplicity. They are crudely-built by the Dutch settlers with hand-forged nails, reed-thatched roofs, and hand-raven oak clapboards. Only three houses in Sleepy Hollow look sturdy with an aura of wealth and refinement. The first belongs to Pieter van Garrett, the richest farmer in the hamlet. Madame Hardenbroeck, Lysbeth’s landlady, owns the other manor. Her fur merchant husband died and made her dowager-rich with a six-year-old son to spoil. Commandant Johannes Montagne, the retired military chief of Fort Orange, lives in a fine house on a hill. The other settlers live between squalor and pinched dignity.

Onheil Manor. Lysbeth walks up the stairs, step by step, passing beautiful black silhouette portraits of different women. Some look short, others are tall, some young, some old, some stout, others slim, some hunched over, others standing straight. The wall collage is clearly the work of a passionate collector. An uneasy feeling comes over Lysbeth. It is the same dread from earlier this afternoon. A time warp engulfs Lysbeth and, through an aerial image, she sees herself look upon Onheil Manor for first time. She is astride Tam-Tam, her beloved horse. They enter the clearing in the forest. The building’s singular majesty in the open air looks wrong. Its smoke-gray timber-frame exterior is just as intimidating as a Crusader’s castle. Lysbeth sees that Onheil Manor has four storeys by the look of the sparse row of windows on its façade. The manor’s two-sided gambrel roof juts out in odd, but symmetrical angles. After Lysbeth descends from her horse, she stands still and survey the cleared, circular land surrounding the building. It is high afternoon, but a late autumn fog has painted the landscape a sooty blue-black color. A flock of crows glide in the sky, and the soundtrack of their haunting cries linger long after they disappear. The golden yellow, mint green, and russet tinted foliage of September already said goodbye to their magical beauty. The end of October is now the beginning of the ugly season. It brings shorter days, darker nights, frozen fields, and sickly livestock. Lysbeth does not see any evidence of daily living at Onheil Manor. She sees no vegetable gardens, no sheep pens, no wells for water, no barn, no oxen, no parked wagons, no horses tied to hitching posts, no chicken coops, no flour mill, no milk cows, no chopped piles of firewood, no enslaved Africans toiling about the place––only a majestic manor in a cleared circle.

Good. I rather see none of my color than broke-back slaves. In Sleepy Hollow, Lysbeth sees many broke-back Africans. In the Dutch village, she stands alone among the sold. At least in New York, the small community of unslaved Africans give a counterpoint to subjugation. Those under bondage and whip can see that their present condition is not natural, nor ordained by God. There is an alternative life path. It stokes their righteous anger and makes them hungry to snatch back their freedom. The enslaved Africans in Sleepy Hollow seem resigned to their prisons, but for their fake, plastered smiles. They nod too eagerly, and quickly, when their enslaver utters an errand or a command. Lysbeth sees the quick frown when their tormentor turns away. Lysbeth sees their looks of confusion, whenever she walked past. She is one of them, but she is not one of them. Dina, Abigail, and Sue, the three enslaved women who churn the butter in the cellar of Hardenbroeck Manor, never look her in the eye when she greets them “Goedemorgen” and “Goedenavond.”

Why do they not look at me? What have I done to offend them? These thoughts prick at her heart like a stinging wasp. Old scars crack open with blood. A motherless child is a rain-soaked chicken little, shivering for warmth, but the hens have scatter themselves to pick at earthworms in the dirt.

All the Africans in New York acknowledge each other’s presence with a nod or a perceptible smile. But the rules in Sleepy Hollow are somehow different. Lysbeth spoke once with Phyllis and that was it. Old Moses is the only one who doffs his hat at Lysbeth whenever they cross paths. The little ones have not yet lost their joy, either. She sometimes see them play and splash each other by the Pocantico River. Cocoa-brown cherubs clothed in dirty rags and doused with free joy and no adult understanding of evil.

***

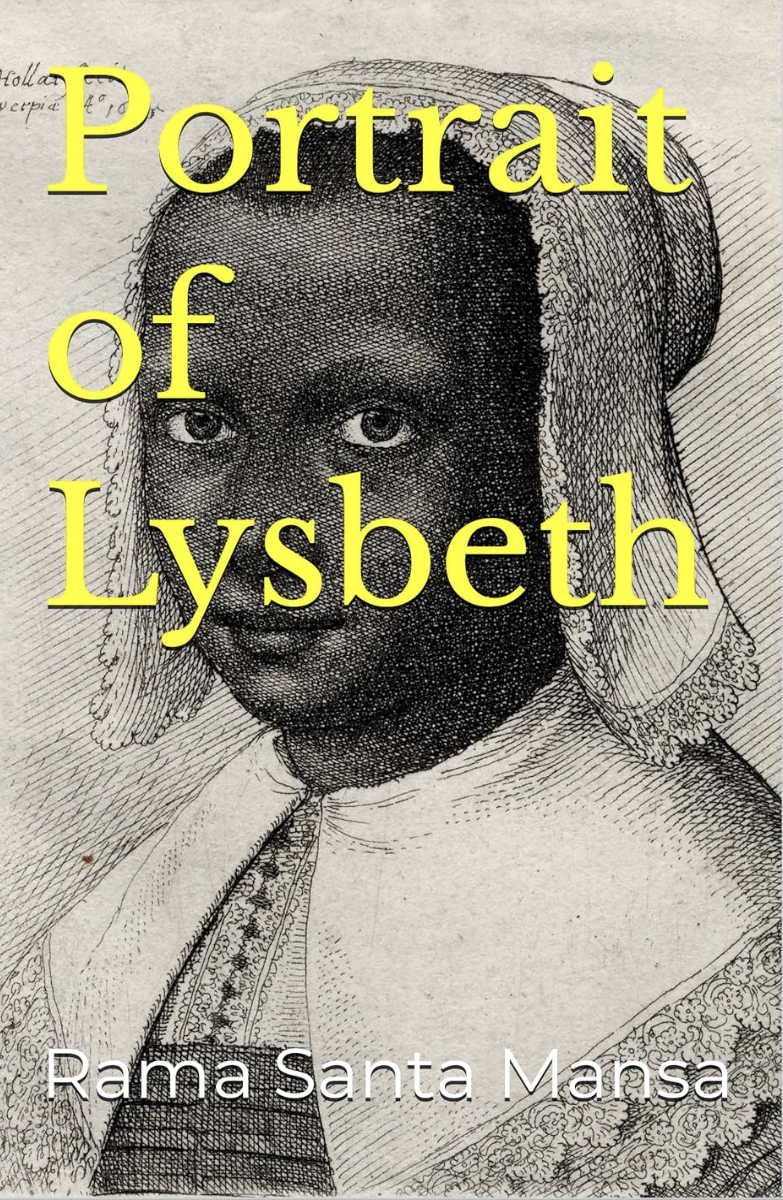

Buy Portrait of Lysbeth here: Amazon | Google Play

Excerpt from PORTRAIT OF LYSBETH published by Lingeer Press. Copyright © 2024 by Rama Santa Mansa.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions