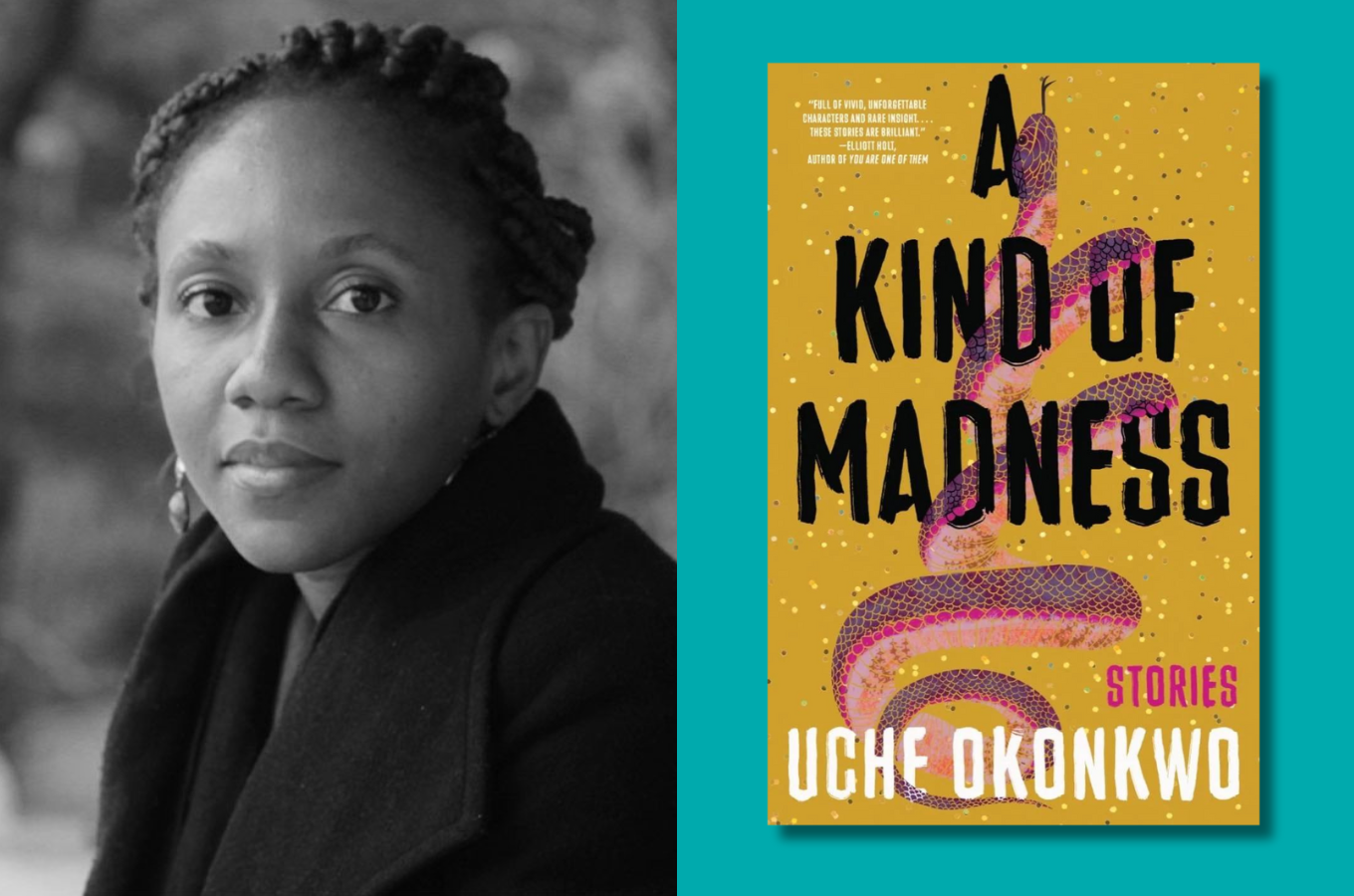

There are books you pick up and wish for two things to happen simultaneously: get to the last page and revel in the satisfaction of knowing how it ends, but also somehow stay reading without arriving at the final full stop. Uche Okonkwo’s A Kind of Madness, a collection of short stories out from Tin House on April 16, 2024, has that effect.

Set in Okonkwo’s home country of Nigeria, the 10 stories in A Kind of Madness explore an overarching theme of madness, real and metaphorical. The reader is still served with a wide range of stories about fraught family relationships, social class, womanhood, mental illness, and more. And yet, in striving to overcome the various challenges of their lives, the characters in A Kind of Madness are pushed, pulled, and tested in their ultimate pursuit of sanity and balance.

Throughout the book, Okonkwo’s signature style of humor, and cinematic detail come alive. There is also a deliberateness in the use of language, a lightness of tone, and a deep psychological engagement with the characters and their life’s struggles.

In “The Girl Who Lied,” the reader is introduced to 11-year-old Kemi who becomes an overnight celebrity in her new school for her crowd-rousing stories. However, beneath Kemi’s rib-cracking tales, is a deeply lonely, and troubled girl craving attention and affection she can’t get from her well-off family. The reader, like Kemi’s best friend, is at once hooked by her ability to make quick connections and challenge the intelligence of her teachers without fear of punishment. However, once the lights go off in the dormitory, once the crowd has disappeared to their bunk beds, Kemi is just a little, lonely girl, stripped of her masks of survival:

I wish I could make them disappear, these girls who kept pecking at her, looking to be entertained…watching her in those moments, I imagined a puppy performing for its owner for a treat. Kemi didn’t just want their attention, she seemed to need it, like it was the only thing keeping her from falling into a dark hole.

In “Burning,” the last story in the collection, Okonkwo ups the ante in how we write about mental health. The reader meets Adanna, a girl forced to become the adult in the home when her mother becomes manic-depressive. Adanna learns to read her mother’s face for signs of outbursts or the occasional sweetness; and when her mother drags Adanna from one healer and pastor to another, the girl must make sense of the insistent claim that she, and not her mother, is mad.

In terms of language, the Nigerianness of daily life, and how the characters speak, underscore a truly authentic voice. As a Ugandan, Okonkwo’s stories read very familiar to my lived experiences, and yet they are fresh and gripping. For instance, “Long Hair” reminded me of the many times teachers ripped through our hair with scissors if we forgot to keep it under an inch long. Our kinky hair was written off as naturally unkempt and unsightly. We watched with envy and admiration as the few non-Ugandan students in our schools pranced about with long, straight hair. In “Long Hair” however, Okonkwo makes the protagonist Nigerian, a move I thought was brilliant in debunking the myth that African hair is only one type of texture. Regardless, Jennifer’s mid-back-long hair and fair skin make her the object of jealousy, and she doesn’t help matters by indulging her school-mates’ curiosities:

She didn’t have any friends—until the day she loosened her hair, which she’d been wearing plaited all-back, for the first time. It was during siesta on a Saturday, and everyone was supposed to be on their beds reading or sleeping or crying quietly from homesickness. But the girls gathered around Jennifer that afternoon, even the dorm prefect, who should have sent them back to their beds. They were all saying how pretty she was….People asked her all the time, Jennifer, are you mixed? Jennifer, is your mother from London or America? Jennifer liked it when the girls asked her these silly questions; you could tell she was the proud type. We had all seen her parents, who were fair like her but were Igbo, not white. Still, she would laugh and say yes to everything: Yes, I am mixed. Yes, my mother is related to the queen of England.

Reading A Kind of Madness, I was reminded of Jennifer Nansubuga Makumbi’s storytelling – the humor, the sharp rendering of issues, and how she stays close to the ways of life and language of her Ugandan characters, something Okonkwo does similarly effectively.

Makumbi had plenty of praise for Okonkwo’s book, writing in part: “Okonkwo casts a critical eye on family and friendships, the ineptness of parents, how the West encroaches on everyday life in Nigeria, the contradictions of chicken as a named entity and chicken in a pepper soup pot. While each story is a world on its own, the collection is at once hilarious and heartbreaking.”

I have known Okonkwo for close to two years, having met her at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln where she’s pursuing a PhD in English (Creative Writing). Having read some of her stories in workshops, I thought I was familiar with her writing style. However, reading A Kind of Madness and its full range of stories in one place demonstrated the extent of her mastery of the short story form. In person, Okonkwo is a person of few, gentle words. Yet, A Kind of Madness demonstrates a skillful audibility of her words – words that grip, haunt, and humor.

***

Buy A Kind of Madness by Uche Okonkwo: Amazon

Bakare May 13, 2024 09:06

Reading a review written by you, is a delight to be enjoyed! I just want to write my own set of reviews and hopefully lead on