The Road to the Country by Chigozie Obioma is prescient in the context of all the wars taking place today. It was hard not to think of Gaza, Sudan, and Ukraine as I encountered Obioma’s depiction of the devastation of Eastern Nigeria. While the book is about the Biafra War in Nigeria, which took place between 1967 to 1969, it speaks to our contemporary moment. It reminds us that wars are awful things that break communities in half, leaving wounds, both psychological and physical, that need healing.

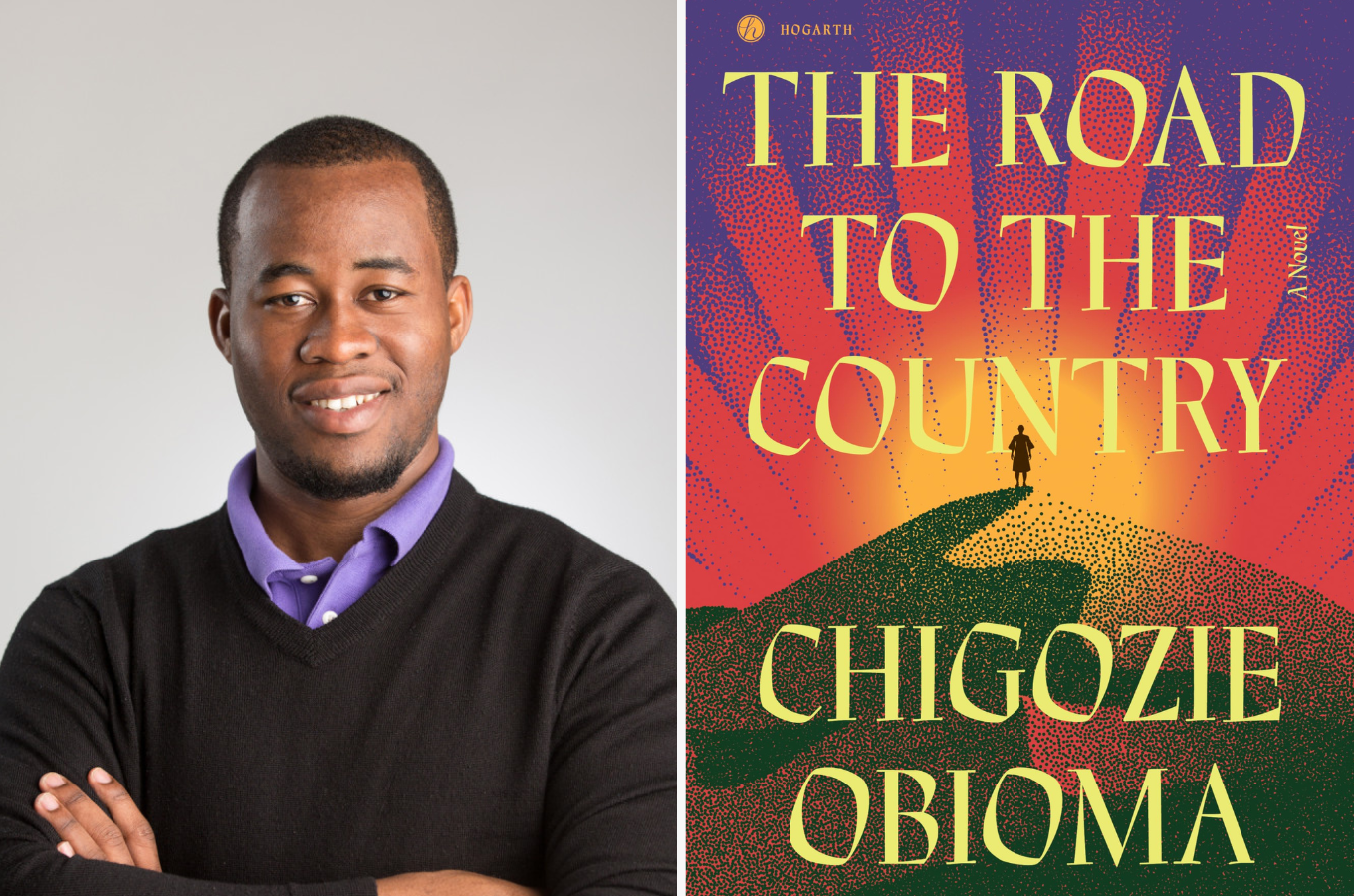

The Road to the Country is Obioma’s third book. His other two novels, The Fishermen and An Orchestra of Minorities, were both shortlisted for the Booker Prize, a huge feat in the intensely competitive world of literary fiction. The novel tells the story of Kunle, an Igbo-Yoruba man from the western Nigerian city of Akure, who sets off to eastern Nigeria to search for his missing brother but ends up being recruited into the Biafran Army. Kunle is a student at the University of Lagos, leading a sad and droll life. As a young boy, in a brief moment of inattention, Kunle’s younger brother was hit by a vehicle and became disabled. Kunle has never been able to forgive himself for the incident. He is emotionally scarred and withdrawn. Despite his parents reassuring him that the accident was not his fault, Kunle can’t let go of the guilt he feels. Perhaps this generally detached view of life is the reason why Kunle isn’t aware that a full-blown war is raging in the eastern region of the country. Everything feels distant and quiet in Akure. But this changes when his brother runs away to the east with a young Igbo woman. Driven by a sense of duty and the hope of finally atoning for what he sees as his misstep, Kunle decides to go after them. His journey to find his brother leads him right into the heart of a war-torn region, where he is forced to becomes a Biafran soldier.

Kunle has all the allure of a dark, brooding, troubled man. But as a character, he is unavailable at first. He is so in his head that we don’t get a sense of what he truly cares about outside of the traumatic experience. But the war does something to him. It opens him up, softens some of the shell. And Kunle becomes our guide through the carnage. But Kunle is not the only guide. There is a seer, an Ifa diviner living in the 1940s, who is also telling Kunle’s story as a set of visions. The novel flits back and forth between Kunle’s life as the narrator depicts it in the moment and the Seer’s account of Kunle’s life in what he refers to as “a yet uncreated time.”

The Biafra War narrative is a well-established genre at this point, with over three decades of both fiction and non-fiction writing by a cast of renowned authors, from Buchi Emechata and Elechi Amadi, to Ken Saro-Wiwa and Wole Soyinka. In the past decade or so, Chimamanda Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun, Chinelo Okparanta’s Under the Udala Tree, Uwem Akpan’s New York, My Village, and Chinua Achebe’s nonfiction title There Was a Country have captured the complexities of the war and its aftermaths for a new generation of readers. Akpan’s book particularly opened new areas of inquiry by addressing the question of minority communities who suffered extreme violence at the hands of both the Nigerian and Biafran armies. Obioma brings yet another lens through which to understand the war by centering the space of combat. He features details about artillery, logistics, army command structures, and the politics of foreign mercenaries. Of the new generation of Biafra fiction, Obioma’s novel stands out in the way it captures trench battle scenes. In a sense, then, The Road to the Country is closer to something like All Quiet on the Western Front than Adichie’s Half of a Yellow Sun in the ways that it focuses on the moment-to-moment experiences of soldiers in the war front.

Obioma writes about the violence of war with a wide-ranging sensorial textures. I can still hear the sound of rain, beating on helmets, amidst the deafening blasts of “106mm recoilless rifles and high-grade mortars.” Eight men are killed instantly. I see where “blood pools in the grooves and flows down the [trench] line.” I see that “Kunle’s shoes are soaked, and [that] he smells of blood and mud.” At the end of his first experience in battle, Kunle recognizes an acquaintance who has been wounded, and describes a heartbreaking scene:

The man lies there, shrapnel lodged in his neck, the left side of his uniform soaked with dark arterial blood. He is blinking, thick blood coursing through his neck like the mealy saliva of a stricken beast. The wounded man struggles to speak as he is carried onto the bed of a lorry loaded with the bodies of a dozen dead or wounded men. As the lorry drives away, rocking as it encounters the ruts in the road, the bodies of the dead or wounded men, propped in seated positions against the sides of the lorry, bounce against the metal railing, and the seated men seems to sway as if engaged in a quiet dance. Kunle, turning, finds that he has begun to weep.

Reading this scene, I feel almost intrusive, like I stepped into a moment of raw emotion that seems too personal to witness. But capturing that moment of vulnerability is important. It is easy to forget that even though wars are large-scale conflicts, they affect individuals. This is what makes The Road to the Country an aching read—it takes you to places that heroic narratives of war or depictions of war as impersonal mass murder do not. It shows the human cost of war in a personal and visceral way.

In the edited collection War in African Literature Today, Ernest Emenyonu speaks of “the role of the writer as a historical witness.” The Road to the Country bears witness to how the Biafra War continues to outlive its official end. Some characters in the novel, on both the Biafra and Nigeria sides, including foreign mercenaries, are actually not fictional; they are real individuals still living today. [See the list here.] This inclusion of real-life figures blurs the line between historical fiction and non-fiction in a way that makes the story poignant. The novel also bears witness to the harshness of the human condition while demonstrating how love can take us much farther than cruelty. It never lets us forget that Kunle is ultimately in search of a brother he loves. The friendships, sacrifices, camaraderie, and bonds he forms with fellow soldiers leave Kunle a changed man. At the end of the day, love is what makes the world of this novel go around. It felt good to witness that.

***

Buy The Road to the Country by Chigozie Obioma: Amazon

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions