I owe whatever I’ve become to the tree from which I fell.

I owe whatever I’ve become to the tree from which I fell.

My parents, Umelobi and Edith Ihekweazu, played an inextricable role in shaping my interests and character as I grew up. Their courtship began at the University of Hamburg, Germany amid protests against the devastating impact of the Nigerian civil war. The era of social activism at the time must have been partly fuelled by the vivid images of the war on television, which highlighted incredible hardships inflicted by the conflict on civilian populations. It was the first major conflict that played out so vividly on TV screens around the world.

Being Nigerian, my father was part of the protests on campus for obvious reasons, but my German mother’s motivation, I suspect, was driven by the pain of being a post-war child herself. She was born in 1941, at the beginning of the Second World War, and the circumstances of her childhood were far from the prosperity that is found in Germany today. My parents fell in love and married shortly after the war ended, setting up home in Hamburg, where my sister, Ada, and I were born.

We relocated to Nigeria when I was about 3 years old, mainly because my parents wanted to help with post-war rebuilding. The post-war period in South-eastern Nigeria was serene and calm, but it was also a period of scarcity and lack. Nonetheless, they both found work at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka (UNN). My mother started as a lecturer in the Department of Foreign Languages, while my father was one of 3 doctors at the university hospital. Our home was a standard bungalow on campus, but what set it apart was that every room had a bookshelf adorned with a rich variety of books. My mother, an ardent reader by virtue of work and leisure, instilled the love for reading in my sister and me from an early age. My childhood in the small university town of Nsukka was a truly unique experience. Subsequently, our family expanded with the birth of my brother, Edozie.

As a young boy, I was fortunate to be surrounded by some of the brightest minds in Nigeria. On many occasions, my parents would host social gatherings with their colleagues and friends from the university community. Our sparsely furnished sitting room often accommodated the likes of Chinua Achebe, Emmanuel Obiechina, Anya O. Anya, Obiora Udechukwu, the Dikes, the Mmaduewesis, and other famous Nigerian writers and academics. To me, they were regular people, but I was always fascinated by their animated conversations about Africa’s progress and challenges. I would sit at the dining table, pretending to be reading while soaking in their conversations. I heard names like Nyerere, Nkrumah and Lumumba with very little understanding of their place in history. I knew that my mother, was fascinated by the work of Frantz Fanon, but I was too young to understand why. The fusion of ideas and opinions resulting from eavesdropping on the musings of great minds sowed seeds of intellectual curiosity that would accompany me for a lifetime. I realised the importance and joy of engaging in meaningful conversations, of exchanging ideas from a place of humility and deepened awareness. These experiences would shape my thinking and influence my approach to problem-solving for years to come.

Our family’s campus home was a hub of activity. We would often wake to the shrill cry of an ambulance picking my father to oversee an emergency at the university medical centre where he worked. Home was more or less a subsidiary outpatient clinic as he would receive patients there beyond work hours—mostly colleagues and their children. In fact, a small storage room in our house was converted into a mini pharmacy stocked with medicines. My father’s dedication to the community was remarkable, and he was highly respected for it.

There was a palpable sense of pride and warmth in being the child of the university doctor. People would give us lifts on the way home or recognise me as nwa doc—child of the doctor. Seeing my father with a stethoscope around his neck as he headed to work defined my childhood. The respect and recognition my father garnered from the community inspired me to be like him, to study medicine and become a doctor. I wanted to impact people’s lives the way he did.

My mother was a trailblazer in her own field, breaking barriers and becoming the first female professor at the University of Nigeria, Nsukka. She was a woman of remarkable persistence and unwavering dedication, and her tireless efforts in the face of challenging circumstances left a lasting impression on my siblings and me. Besides her work, she was deeply involved in the Children’s Centre Library as well as the University Women’s Association. She encouraged us to read widely and explore our interests, fostering a deep sense of curiosity and love for learning (there wasn’t much else to do other than read and play anyway; we didn’t have a functioning television at home for most of my childhood). Her typewriter could be heard every evening echoing through the stillness of the night as she typed her manuscripts.

In 1983, at the age of 12, I was accepted into the Federal Government College, Enugu (FGCE)—my first time away from family. Boarding school life was tough, especially during the first year; I had more sad than happy days. While I enjoyed attending classes and expanding my knowledge, the hours between the end of lessons and supper were particularly difficult. The older boys in the dormitories would often take advantage of younger students like me, forcing us to run endless errands such as fetching water for their baths, buying bread at the tuck shop, or doing their laundry. If we were found in the hostels on afternoons, it meant a never-ending stream of errands and chores. I spent many afternoons with my classmates, wandering the sports fields in exhausted boredom to pass time and steer clear of the older boys. Today, I’m grateful for the friendships that were built from this challenging situation. They sustained me through boarding school and thereafter.

In 1989, I sat for the national exams that would determine which university I would attend and was pleased to gain admission into the University of Nigeria to study medicine. This was the culmination of years of hard work and dedication, and I was determined to make the most of this opportunity to learn and grow. My first year at medical school was a time of exploration and fun. Instead of burying myself in textbooks, I found myself basking in the campus social scene, enjoying every moment of it. I occasionally had access to my parent’s vehicle, given that we lived on campus, and I relished the social capital it afforded me.

During the summer vacation before my second year, I travelled to Germany to be with my mother who was on a research trip. While I stayed behind in Germany to spend more time with my grandmother, my mother headed back home to Nigeria. On her way to Nsukka, she was involved in a head-on collision with a trailer that was overtaking a vehicle.

She didn’t survive the accident.

***

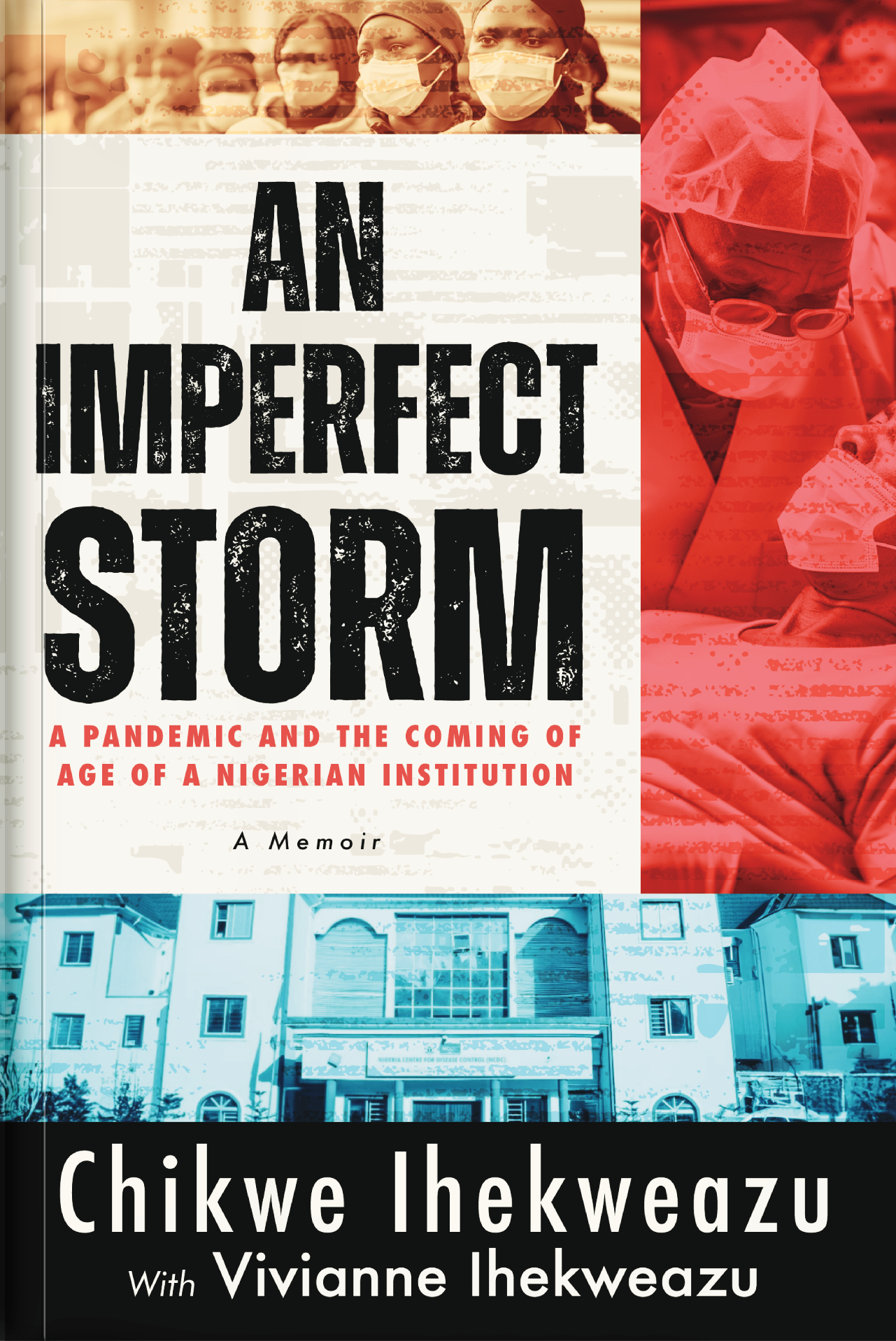

Buy An Imperfect Storm here.

Excerpt from AN IMPERFECT STORM published by Masobe Books. Copyright © 2024 by Chikwe Ihekweazu and Vivianne Ihekweazu.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions