“And so our mothers and grandmothers have, more often than not anonymously, handed on the creative spark, the seed of the flower they themselves never hoped to see; or like a sealed letter they could not plainly read. Guided by my heritage of a love of beauty and a respect for strength—in search of my mother’s garden, I found my own.”

— Alice Walker

For a while now I have been grasping at the truth that I come from a lineage of powerful women, women who have, as Alice Walker describes, “dreamed dreams that no one knew-not even themselves.”

But what happens when dreams once deferred now frolic towards fruition, propelled to come to life, shape-shifting, connecting dots across generations? My grandmothers’ hopes, my mother’s dreams, and my own beliefs weave a tapestry beneath our feet. A harvest of dreams that offers us a new story of who we are, bending us towards our power and strength. The dots that once seemed hidden are now connecting, outlining a new narrative that declares, I AM a multi-generational storyteller. This is the legacy of my mother’s pain.

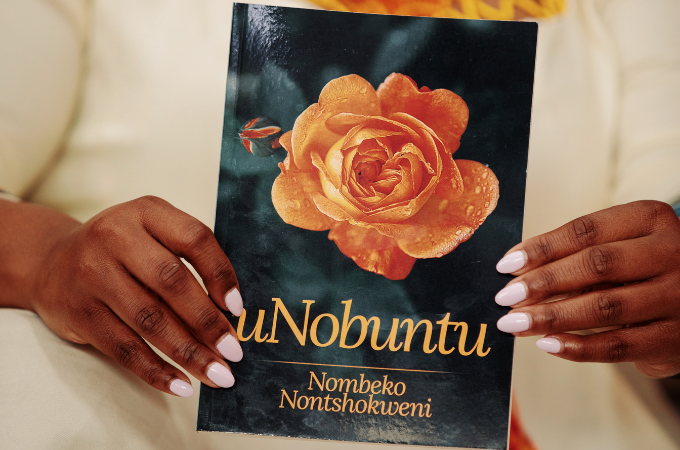

Mama was only twenty-one when she lost her first child, uNobuntu. At the crack of dawn, the news arrived at her door, announcing that her exquisite beauty, the purest product of her love, had been “borrowed” as an “offering to the heavens.” The sun set early on my young parents’ lives on May 29, 1983. Newly married, they were “unprepared for the intensity of sorrow” that was now theirs to live with. Mama turned to the pen — to write, to weep, to grieve, to heal — and this pain became the birthing place of her first book, uNobuntu.

It would take forty years for this sacred work to be published. Between raising four children and caring for the family, all single-handedly, her manuscript gathered dust. All throughout changing houses, careers, and finding the right schools for her kids, she carried her manuscript as though it were her fifth child. In 2022, the uNobuntu documentary captures the emotional moment that Mama finally holds her newly published book for the first time, adorned with a fitting cover of green – for her pursuit of growth – with an orange rose – the long-lasting memory she has of her little girl in an orange onesie.

A portrait of the quintessential, post-millennial South African family, a devoted daughter helps her mother fulfil her life-long dream of publishing a treasured 40-year-old manuscript. This story of hope, and triumph, goes against the backdrop of prevailing stereotypes about the culture of literacy in Africa. Instead, it lifts a contextual, hidden narrative about black women “writing their story anyway,” and shaping the intellectual traditions of their lineage.

We had the immense privilege of showcasing this work at NBO Litfest. We spent a grueling amount of time translating Mama’s isiXhosa anthology into English so her Kenyan audience could experience the pulse of her story on the page. The room was full, the lights dimmed, old and young Kenyans sat still as their own grief gnawed in light of my mother’s story. At the end, hand after hand rose to ask a question. This screening called to that untrammelled space where the inner voice grows free to speak. In my mother’s story, the souls of old and young had something to say, all chanting, “heal me.” Even slight echoes of Rumi could be heard in the plea for light to enter through the wound

One audience member spoke of losing her father, grieving in silence because she now had to take care of her mom, who was her father’s primary caregiver. Her mother was finding a new identity and she had not yet found the space for her own tears. Another young man, who described the uNobuntu experience as “deep therapy,” asked how to turn the tide of time so his mother’s passing would unite his family rather than divide and erode them as it had done. Another festival volunteer acknowledged that gathered in that room, her grief ripened into tears as she wept for her grandmother.

Boundless was our balm of healing at Eastlands Library, bottomless the extent of rapture and pain. For a moment, the space expanded enough for each of us to admit how unsure we all were of how to heal. We could track with our fingers, outlining the sores in our souls to finally tell what the pandemic had done to us, the losses in income, identities, and loved ones. In those sacred moments on stage moments, I watched my mother, a reservoir of love, open her heart wide and pull from her center to offer back rubs, big hugs, lines from her beautiful book, and wisdoms that had come through the years, reminding all in the room that “there is a time to mourn and a time to heal.”

The organizers of NBO Litfest found the book and documentary so compelling that they selected it as a catalyst for their “Missing Bits” project. This segment of Book Bunk records audio narratives of Kenyan communities. Those marginalized stories that seldom make it into books and libraries, so a wider array of stories would shape the archive. The public was invited to record their stories responding to the question: “Have you or anyone you know suffered the loss of a loved one, job, health, identity, relationship, security, pet, or any other significant aspect of your life?”

uNobuntu, the book and documentary, entered Kenya’s door just as her people knocked. The story was ripe for its time carrying a profound responsibility to comfort those who were broken hearted. To inspire those whose hopes had become deferred. Mama’s life and story felt the ushering of peace and promise, dripping her book, leaping from the documentary straight into the hearts of mothers who had alike lost their own, but their grief was trapped in silence. uNobuntu was like oil in those empty fractures that silently hide in our souls, unattended, hidden. She fell like blossoms calling each of us to remember that our heartbreaks are universal. That our healing is collective, and that our stories, when told authentically, are each other’s balms.

uNobuntu the English Translation is now available to pre-order to be released on Womens Day as a reminder to us all that “In search of our mother’s gardens, we find our own.”

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions