Chapter Nine

The night was warm, and the mosquitoes unobtrusive, their presence announced only when they pricked the bare legs and arms of a patron at Shigudu’s. Around Zanya, customers buried their heads in steaming bowls of pepper soup, and he caught a glimpse of their faces when they needed to wash down the ganda or cool their tongues with a swig of beer. Zanya and his laborers did not eat, though they occupied two of the seven tables and congregated under the light bulbs hung across the bar’s tin roof.

Victor Uwaifo’s voice came from a radio somewhere above their heads, singing in tune with the twang of his guitar. Two women arched their backs as they pounded yam, their chests heaving with each rise of their arms, pounding in tune with the song, while Shigudu’s son grilled moist flanks of grasscutter, fanning smoke that blew in his direction.

Shigudu stopped at their tables to see what the laborers wanted to eat and drink.

“With which money?” Betabwi said.

Shigudu said, “No money? And all of you are here?”

The rumblings of his men’s stomachs reached Zanya. He placated Shigudu by ordering beers for the men and a mineral for himself.

They had come to Shigudu’s since their first building project, and though the laborers felt the tightness of their pockets now, they came for the atmosphere and the ritualistic aspect. Zanya drank his Coke and listened as his laborers argued about the Igbo returnees coming back to reclaim their homes and businesses in Rabata and attempting to reenter their roles in universities and the military. It was too early to know how they would reintegrate into Rabata and other cities and towns in Nigeria. The war had bred animosity and distrust.

“Biafrans made a good attempt at this war, o. They should be treated with respect when they return,” Kago said. “War is war, but their efforts should be rewarded—”

“Who said we would not respect them?” Betabwi said, as if he were the head of a university determining which person to employ.

“He’s not saying we won’t,” Zanya said in Kago’s defense. “Three years was long for those soldiers to fight, for them to have resisted federal troops. Chubz will tell you.”

His friend Chubz worked for Glories and Blessings Ladies Provisions Store and had yet to be convinced about the Christian practices of the mission. He was the only person most people in Rabata knew who had fought in the war, so they called him General. He had come home with a pinned shirtsleeve flapping against his side like a folded pillowcase where his left arm used to be. “Shrapnel in Okikra,” he said when people asked. Chubz had the somber and dignified expression of a soldier, and one could picture him with the hard helmet and military uniform, shouldering an AK-47. Chubz was fond of saying he had gone in whole and returned seven-eighths. He would say he counted himself lucky to have only severed his left limb, and the townspeople would know he was thinking of the misfortune that befell his comrade in the explosion of a bridge connecting Obot Akara and Umuahia. I saw the whole thing with my koro-koro eyes, Chubz would say. Chubz had told Zanya that the military training he received in Accra had been preparation for peaceful times, not war. As a result, they had not had enough trained men in the Federal army to quell the regional rebellion.

One of the laborers said, “Ojukwu was lying to this country. Tricking all of us. He was collecting his weapons for war while people were laughing at him.”

“Like the Reverend,” Betabwi said, taking a swig of beer.

The men laughed and one agreed, “Yes. Like Reverend.”

A laborer said, “You go compare Reverend Jim with Ojukwu?”

“Liars, the both of them.” Betabwi looked around at the other men and licked his lip, gearing up for a rant. “Reverend get money and him no wan pay us.”

“Monkey dey work, baboon dey chop,” one of the men called, and the others laughed, and a couple of them said it was true.

Zanya had thought his laborers’ silence these past three weeks meant they had accepted the situation. They had made progress on the church. They had raised wooden scaffolds to build the walls. A church member felled a tree on his farmland, and they had sawed the wood and transported it to the construction site. He and Betabwi had hauled the timber from the pickup one afternoon, while the sun, a brutal force, piloted its rays on their perspiring foreheads and backs, and sawdust specks blew into their eyes.

Perhaps the laborers desired more, like him. Maybe new trades or training for different skills when construction projects were unavailable. The church could help the laborers in other ways. He reached for the pen and notebook in his trousers.

“You and this-your notebook,” Betabwi said, scoffing. “What does it say? You dey write: Make Reverend give wages to dem laborers?”

Zanya laughed with the men and put the notebook away. “Betabwi, we suppose work. Even if money dey small.”

Kago said, “I no for complain if dem dey pay us better money na, but dis money, e no do.”

“Kago,” one of the laborers said, “since the first day, you’ve been siding with Reverend Jim. Anything Reverend wan do, I go see Kago there first. No be so?”

“I’ve changed,” Kago said. “I’ve changed. I’m seeing things now.”

Another man, one week on the job, spoke up. “Ehn, Zanya, make you go talk to dem for us, na,” he said. “That’s why you be oga. See as you tell me make I come join in this work and I agree. Na you wey we dey look, o.”

“You that have just come,” Zanya said, “see you asking for more money.”

The laborers chuckled, and the man was briefly embarrassed. He conceded, “No problem. I no stay for here long, but I dey see how things dey work for here.”

One of the women who was pounding yam earlier came and collected their empty bottles from the table. As she strutted off, Betabwi swiveled in his chair, and his lips curled in lascivious pleasure, appreciating the bounce of her bottom.

A laborer next to him said, “Betabwi, you wan fourth wife? Wetin you dey look, na?”

“Man get eye,” Betabwi said. “I just dey admire dey work of God.”

“Reverend talk say make we remove our eye, o,” someone said. “If eye go cause sin.”

Betabwi laughed, “Ehn, make God come knack me for eye!” He turned back to Zanya. “You go talk to Reverend about this money matter? See how I dey work with this my body. If you don’t do something, Zanya, this church will never be built.”

“Wetin you dey talk?” Zanya looked around at the other laborers. Some stared at their half-drunk bottles and rolled the bottle caps in their palms. A couple gave him defiant looks and leaned against their chairs, arms folded. “You’ll stop building the church?” Zanya said, catching the drop of Coke that almost trickled down his chin. “Is that what you’re saying?”

“Make you tell Reverend,” Betabwi said, staring at him, “and he go do am.”

“I dey hear you,” Zanya said.

“Fiya Boy,” Betabwi said, raising his bottle. “Na God wey save you from de fiya wey dey your village. Na you fit handle dey Reverend.”

“Fiya Boy!” another man called.

“Fiya Boy!” the men shouted in unison and clinked their bottles to Zanya. Women carried more pounded yam, egusi soup, and pepper soup to the surrounding tables. Music flowed down from the speakers as the laborers’ chant rose into the night.

Fiya Boy. The words echoed like a taunt in Zanya’s ears as he sipped the dark, sweet liquid and eased himself into the shadows of men.

***

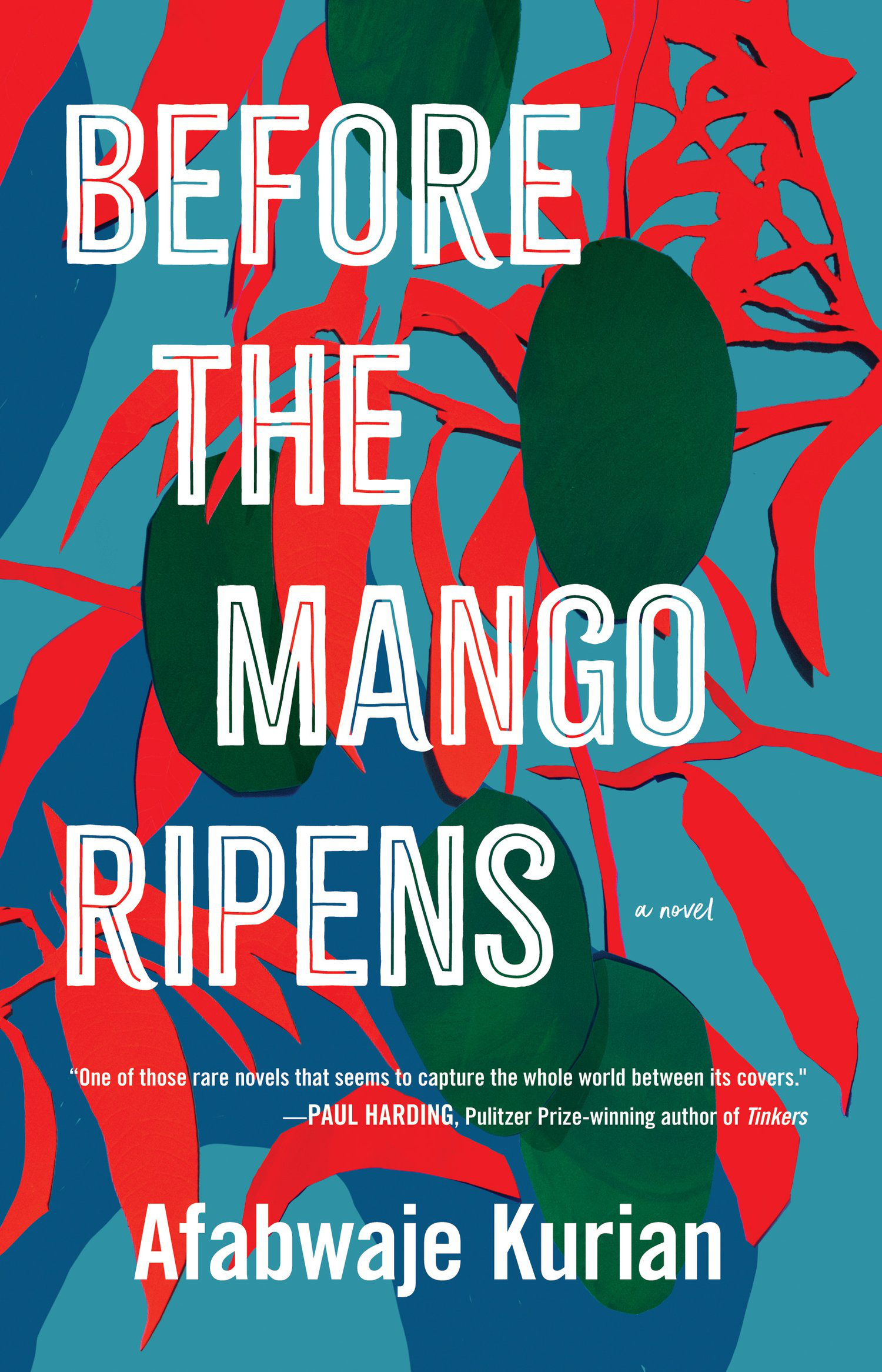

Preorder Before the Mango Ripens here: Amazon

Excerpt from BEFORE THE MANGO RIPENS published by Dzanc Books. Copyright © 2024 by Afabwaje Kurian.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions