But Ngozika wished the man could stop so that everybody would have a chance to try to hear her heart crumble as the rain continued to water her husband’s grave. She was not known for this, for this sentimentality, but here she was.

This bus, when it galloped again, brought to mind the last scene in Ernest Hemingway’s novel, The Sun Also Rises. The book might not have been her favourite novel, but Ernest Hemingway was by far her favorite. The Sun Also Rises happened to be the book she was reading when the Nigerian-Biafran war began, and now she, like the protagonist in the novel, Jake, was in a vehicle.

If the couple behind her were inclined to literature, Western literature, she would say, “Isn’t it pretty to think so?” to bring an air of elite cheerfulness into this suffocating vehicle and see if they could forget their plight, but the man and his wife were clearly illiterate like most Biafrans and Nigerians. She closed her eyes, and that memorable question (“Isn’t it pretty to think so?”) echoed against the walls of her mind. It interested her that the speaker, Jake, referred to the idea that he and Brett, the object of his attraction, could have had “a damned good time together.”

She had felt sorry for Jake when she had closed the book, and now, to her surprise in this situation of hopelessness, her heart went to the author. What could have pushed the great man of letters to take his own life? She wished she could take her own life, but who would care for her kids? Who would give them the education they craved? She had no formal education, but she could read big books, including encyclopaedias and dictionaries. Virtually all the women she knew could not read or write. Her gratitude would always go to her grandfather who taught her in her childhood. The old man did not fly overseas, but he had worked with the Pink people in Onitsha and in Lagos. It was a publishing company that printed newspapers and magazines. But the old man had transitioned, his son had transitioned, and she, the wife, would soon transition if this war continued.

Her son, sitting on the other side of his sister, seemed to read her thoughts, her dark thoughts. “Stop thinking about death.”

“Oh God,” she said and tore off some strands of hair. They fell off her hands like odd black petals.

Staring out the window, Ngozika squinted into the rainy darkness until her worst fears became visible in the distance. The driver stepped on the brake with ominous suddenness, and the men on the bus asked him, in panicky tones, to reverse and take the road by his left side. With squealing tyres, the bus turned, rumbling off-road, crushing tins and bottles and singing praises for God. The melodious voice of Celestine Ukwu had retreated, and the air reeked of soured foods and rotten things.

When they appeared on the tarred road, she glanced to the side to see if her children were dozing. Udoka held Emeka, and the boy, as always, was looking out the window with an expression of stoic heroism.

“The fire burnt the barn?” Emeka asked to split the clumsy silence that sat around them like tattered things.

“Everything!” Ngozika recalled with a start the black smoke coming from her kitchen. Hopefully, the fire would run out of fuel and sputter to die. Glancing out the window, Ngozika leaned forward in her seat. The sky was grey in parts but mostly creamy and whitish, like smoke. Black birds circled the sky, and some dived into the green grasses and the dust-coated trees flying by as the car galloped.

“Everything?” Emeka asked.

Ngozika sighed, then searched her son’s face. He was so thin and tall, but she was not tall. She had the body of a woman who fed four times a day, even though she could not remember the last time she ate twice. Her gown, lemon and torn, was what she wore the day her husband died. He had bought it for her, which made it even more special. But she was not interested in romantic sentimentality now. She would have liked to change her clothing and her children’s, which were worse. Theirs were black rags, and their faces, like their hands, were shriveled as if they belonged to old people. But theirs were not the worst; many children of Biafra already had swollen bellies, and hopefully Emeka and Udoka would be saved in her village.

Ngozika glanced at her son who was staring at her with curiosity and said, “You heard me right. Everything.”

“You sound like you’re angry with me,” he said, ignoring the prying eyes of other passengers. “I am not the Nigerian soldiers that set it on fire, am I? Why are you angry with me?”

Black smoke seeped into the bus through the broken windows, and she waited for the winds to blow them away before she said, “I am angry with everything God created. Everything.”

“It’s all right, Mama,” he said, coughing with a few people on the bus. “It’s all right.”

The journey became less depressing when a black-coated and white-haired man rose from the first row of seats and asked everybody to close their eyes for prayers. “We need to hand this journey into the capable hands of our Lord Jesus Christ,” he said and coughed. “Many of us are corpses down there. I mean, from where we came. Many of us are corpses, but we are alive on this bus, running away from danger and to safety. God is with us. God is still with us. Let us pray for consistent grace and worship his infinite kindness and grace. Amen?”

“Amen!” the passengers chorused, and Ngozika looked round to see their faces. Most of these Christians, Ngozika observed, were women: young women, married women, bandaged women, pregnant women, and women with little children. Very few men responded. But she was not in the mood to ponder or speculate the reason or reasons why broken women, these broken women, were keener on God than men, these equally broken men.

Ngozika imagined her husband decomposing in the grave near his house, and a cold thing sank in her heart. She closed her eyes and visualized him sitting next to her on the bus.

Nnaemaka? she asked in a delighted tone, a stone rolling off her heart. Nnaemaka?

He put his hand on her shoulder and said, in English: Yes, darling. It is me. And I have missed you.

You have changed. Your beard, your eyes, your skin.

What happened to them? he asked, rubbing his unkempt beard and staring at his shrivelled hands.

God, you have changed. Nobody was feeding you? Are you hungry?

Her husband laughed, a short ghostly laugh. Then he said: We don’t eat food over there.

Our children cry every day. They miss you. They need you. Look. See them, Emeka and Udoka.

I will be with them when their own time comes. This is your moment.

Ngozika leaned into him to cuddle, but something—what was it?—restrained her. She said: When will you come back to stay with us? To stay with us forever?

Until you learn to control your anger, he joked.

But she did not laugh. She only mumbled: Okay. Okay.

I am sorry if my joke was insensitive, he said, running his hand through her hastily combed hair. Where are you going to? Where is the bus going to?

I am going to my village with our children, she answered.

Until the war is over? he asked.

She moved closer to him to see if he wore his favorite Tony Montana perfume, and he did. She usually sniffed him when they were close like this and he smelled nice, but now she only frowned and said: The war will never be over.

***

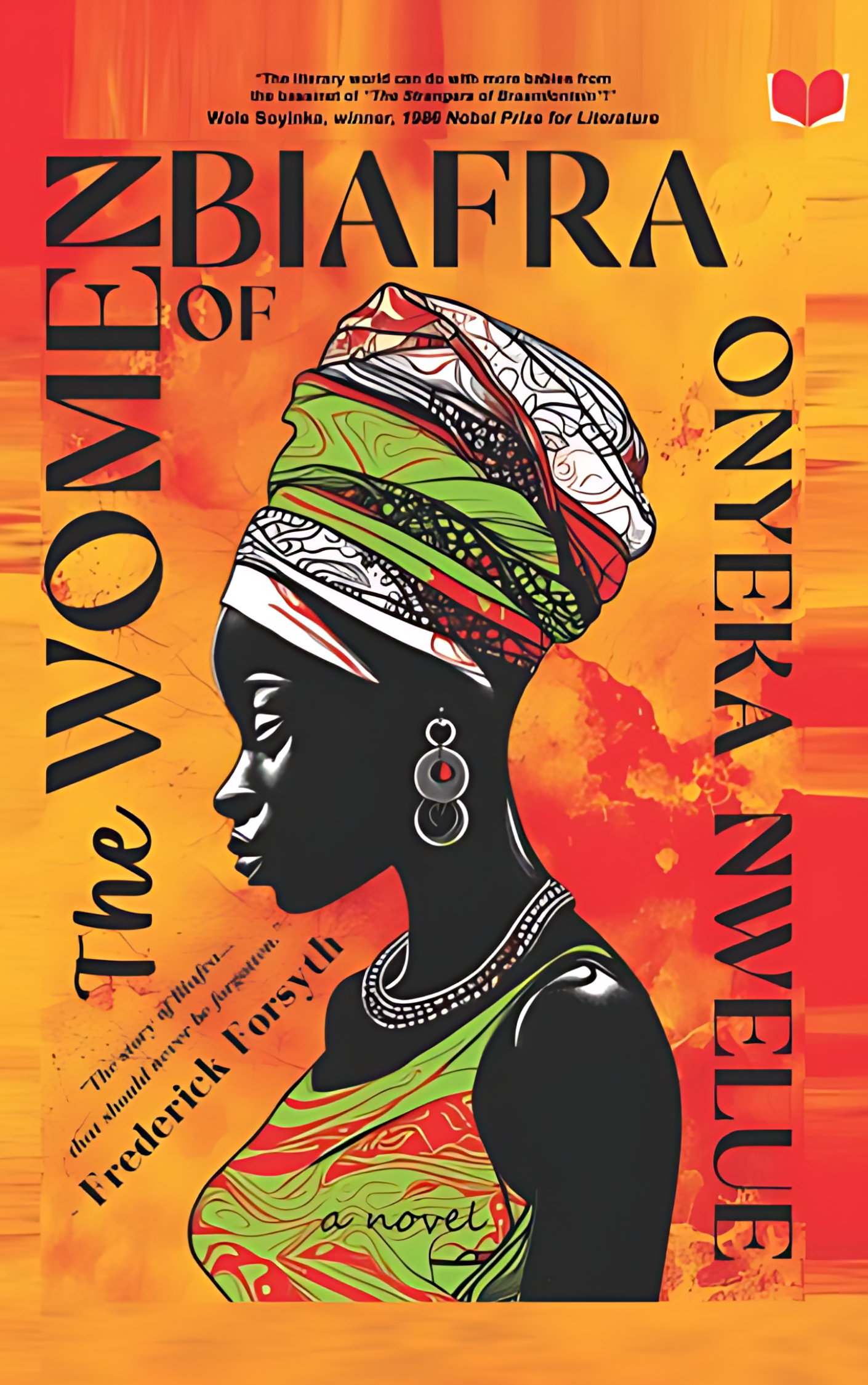

Order The Women of Biafra here: Amazon

Excerpt from THE WOMEN OF BIAFRA published by Abibiman Publishing. Copyright © 2024 by Onyeka Nwelue.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions