“The Light Conspired to Gift Her Images”

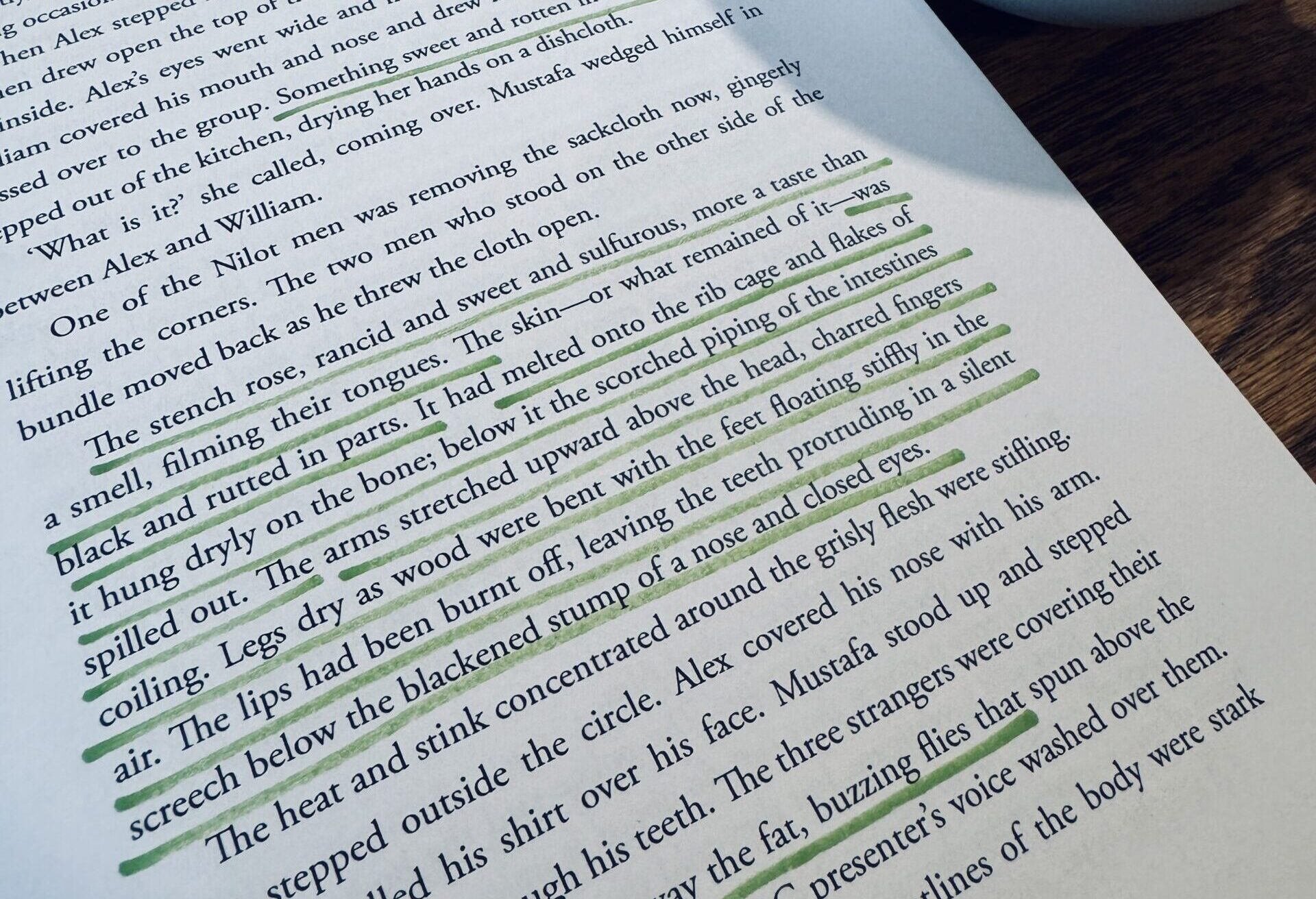

Page 59, Ghost Season

Ghost Season by Fatin Abbas takes you to Saraaya, a fictional town rich with crude oil, located at the border of Sudan and South Sudan. Abbas was born in Khartoum. She experienced the upheaval of the 1989 coup that forced her family to move to New York City. But, her ties to Sudan remained strong, and she drew from these experiences, particularly her time in the town of Abyei, in crafting the world of Saraaya, a place of quiet mystery and tension.

What stayed with me as I read the book is the way Abbas can turn stories into powerful images. This has to do with her way with words, a special gift she has with describing things (see more below). But I think the visual character of her storytelling also comes with how Abbas sometimes structures what the reader sees with the lens of a camera, a quirk that makes the world of the novel both strange and familiar. It’s like looking at a scenery captured in a photograph and imagining that you’ve been there before. It may also just be because my favorite character in the story is Deena, a Sudanese American filmmaker, who always has a camera and is constantly taking videos of Saraaya and its people.

The novel opens with visual and sensory intensity. Three Nilot men arrive at an NGO compound with a burnt corpse and ask Alex, an American geographer, to help transport the body. Abbas’ description of the moment is a chaotic mix of sensory experiences. What you see, smell, and hear throws you into the scene without warning. You feel so many things before you can step back to take in the whole moment. The scene is dark and macabre, but it is also a bold way to invite a reader into a fictional world. Though the unidentifiable body recedes to the background, it repeatedly resurfaces and raises questions about where to bury it, reminding us of the town’s divided Christian and Muslim communities, and the broader tensions between North and South Sudan.

The characters go about their lives amidst rising tensions. Alex, who is mentioned earlier, is creating a map of the area for an NGO often referred to simply as “the organization.” There is Deena. William is a Nilot translator, who is also working as a fixer of sorts for Alex and the organization. There is Mustafa, a teenager who does housekeeping and Layla, the cook, the love interest of William. All these characters navigate their own roles within the rising tensions in the town. In spite of their ethnic, religious, racial, and class differences, they live out the complexities of their identities and, in the process, figure out the bonds they must forge to survive the coming turmoil.

What really stuck with me is how Deena’s work as a photographer captures Abbas’ world-building. I found myself looking forward to the descriptive passages. Abbas’s descriptions go beyond the usual—they create vivid, standalone images that feel almost tangible. This is likely because Deena’s photographer’s eye shapes the story. At times, reading the novel is like scrolling through an Instagram feed of striking scenes and landscapes. Typically, descriptions serve as placeholders between character-driven moments, but in this work, they make the story. Through Deena’s lens, everything looks memorable, no matter how fleeting, mundane, dark, gory, or lifeless. Even when her camera fails to capture the full depth of a scene, the narrator still manages to describe the flatness in a striking way.

Light conspired to gift her images. She framed the cattle in front of her: collage of flicking tails and rear ends and horns and mottled fur, sunlight streaming down in dusty ribbons, patterns of color and light, cow markings and spots of moving shadow. The slow shifting of the cattle as they tore at grass gave the picture an undulating quality, light and dust and color altering from one moment to the next. The animals moved against the fray of the land and the deep orange sky, a hundred crescents in silhouette. With her index finger she reached for the filter switch, the picture flickering lighter and lighter. The adjustment aperture, the steadiness of the device in her hand, framing and panning, came to her without forethought. ..

There is this moment when Deena thinks about her work as a photographer in comparison to Alex’s work as geographer: “How could she explain this feeling, this flow…What she was interested in was a gesture, a quality of light, and the motion of a herd of cattle—things that eluded measurement.” She’d trained to become a painter, but that didn’t interest her. She went to film school but had no interest pursuing studio filmmaking.

What captivated her was capturing seemingly “meaningless scenes” of people, animals, and places. She’d amassed random bits and pieces of footage and was desperate to weave them into a “picture of the town,” but she doesn’t realize, at least not initially, that her power as a photographer—and perhaps Abbas’s power as a writer—lies not in creating a complete portrait of the town, but in capturing those elusive moments that can’t be measured or mapped.

In the end, Ghost Season is about a town grappling with its place amid powerful local and global forces. But it’s also about finding beauty in the unmeasurable, mystery in the everyday, and exploring the tension between what can be captured and what remains elusive.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions