As a literary scholar, I spend so much time trying to understand, explain, and analyze literature, always looking at it through these big, overarching frameworks and trends. But poetry? Poetry is where I retreat. It’s my joy as a reader, not a scholar. It’s where I’m okay with not understanding an entire poem, where I’m fine if all that speaks to me is a word, a phrase, a sound, or even just an inflection. Poetry is the one kind of writing I’m grateful for, even when I don’t understand a single word. So, I read Mary Alice Daniel’s Mass For Shut-Ins in my usual way—just letting myself feel it.

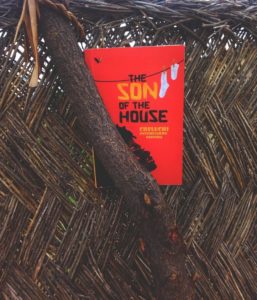

Daniel is a Nigerian writer. This is her debut collection, which was published in 2023. The poems touch on a range of issues: racism, misogyny, gender-based violence, climate disaster, colonialism, slavery, even Zambia’s 1964 space program. But what struck me most was how she uses religious, ritualistic, astrological, and astronomical images to question what’s wrong with the way we treat the earth and certain lives. In her poetry, someone’s casting a spell, looking up at the stars, thinking about the moon, wondering about serial killers, pondering what demons do in their downtime, asking if a girl’s name is proof of being loved, wondering what the dead would say if they could finally speak, gesturing toward the supernatural, evoking the violence of slavery, talking about trees, reflecting on death.

For reasons I can’t entirely explain, I was really drawn to the poem “Wolfmoon.” Astronomy fascinates me, but what’s even more intriguing is the culture of myth-making that various traditions have built on top of astronomy. Today, the obsession with space is at an all-time high, possibly, the poem suggests, because we hope to discover a new earth. The poem references the somewhat whimsical effort in the 1960s by Edward Festus Mukuka Nkoloso, a Zambian science teacher and nationalist, who wanted to send the first African astronauts—referred to as “Afronauts”—to the moon and Mars. In the poem, Daniel references the Afronauts in relation to the phenomenon of moondogs—those “fake moons” that appear when extra bright moonlight hits ice crystals in the clouds. At the heart of the poem is the idea that we keep coming up with all kinds of “eccentric space programs,” perhaps hoping they’ll solve the problem of a dying planet. But there are no secrets in space that can save us, just as the extra moons in a moondog are a trick of the eye, just as Nkoloso’s catapult will not send “a space girl + her pet” to Mars. We need to fix what we already have; we need a better world here and now, not a new, eccentric one out in outer space. As the opening lines say, “We don’t need more types of moon / We just need a better moon / one that gives more room.”

Another thing I realized when I allowed myself to experience Daniel’s poetry without trying to dissect every line or pin down every meaning is that Daniel has an uncannily beautiful sense of rhythm in her work. You know a poem has a beat when you find yourself reading parts out loud without even realizing it. That’s because you can feel the call and response, the way the words and phonemes touch each other, inviting you to respond with your voice, to speak out what’s on the page. Some say that oral cultures understand the magic in voice, that voice comes from the body, that it is meaning that resides in us—the breathy, fleshy language of possession. So I’d start reading Mass for Shut-in, and before I knew it, I’d be voicing the words. I don’t know why but some poetry resist their written form. They reach beyond the page, where they are held down by print on paper so they can move your soul.

Mass For Shut-Ins is a collection that speaks to you with everything: the typographical layout, images that touch something deep and personal, questions that bring up feelings about all the big stuff like death and the human condition but also rhythms that make you want to speak the poem in your truth.

Buy Mass for Shut-ins by Mary-Alice Daniel: Amazon

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions