Lonyaka, lomhlabathi womile; asazi sophelelaphi thina. Bazali khwelani kuleyantaba, liyothethela amadlozi

– Lovemore Majaivana, “Litshisile Lonyaka”

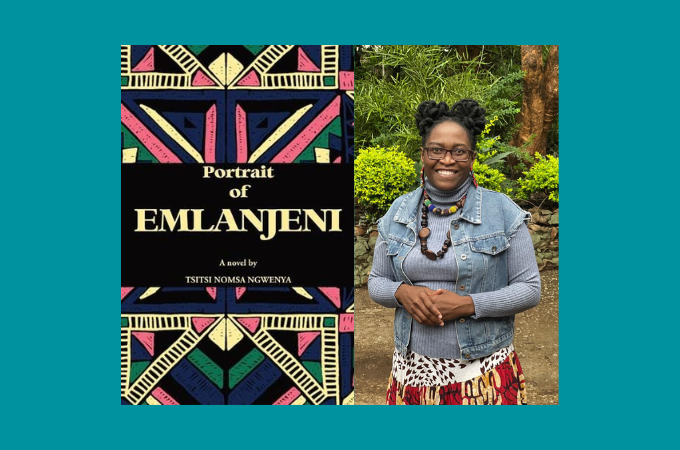

Tsitsi Nomsa Ngwenya’s debut novel, Portrait of Emlanjeni, is named after its vastly diverting setting: Emlanjeni Village in Zimbabwe’s Matebeleland South Province. A fistful of readers agree that the village itself is a, if not the, leading character in Ngwenya’s book. According to literary critic, Vuso Mhlanga, Ngwenya carefully presents “the breathtaking environs of Matobo (a heritage district where the fictional Emlanjeni is located) as a rich and key character to this novel just like in Cry the Beloved Country or Waiting for the Rain.” Ngwenya and her editor, Dr. Tanaka Chidora, agree that making the village a character was a deliberate undertaking.

The magic strong enough to transform the village into an anthromorphous entity is its community ties. Emlanjeni disarms us with its innocent charms, away from the rot and rote of city and diaspora. Its children may carry on dangerous crime and default on self-care in neighboring South Africa, but “their characters are miraculously revived the moment they come back to Emlanjeni.” The strong sense of community Emlanjeni impresses on its prodigals makes good times in the village “a fluttering fancy like the heaven preached by Christians.”

There is a lot going for the rendering of Emlanjeni village as a living character. Just as Thomas Hardy’s small-town idylls use some shaping from his architectural background, town planner Ngwenya is an old hand at conjuring place. Homely vistas spread out as Emlanjeni falls back on its “ancient” customs – too many African laws and values merit this colonial timestamp because they lately count for fame rather than force, in the era of the modern state – to find justice that does not always seem to be at home in its lawyerly halls.

But there are bills to be paid for heaven on earth. A dark mass of silence. The many personifications that give character to Emlanjeni Village are that of a place learning to live with death. From here, we are one step from spinning the anthromorphous rendering of the village on its head. In the new form, the (alternative) main character of the novel, a little girl named Khethiwe Sibanda, herself embodies Emlanjeni Village. I note, in a previous discussion of Zimbabwean novelist, Andrew Chatora: “In the Persian classic, Sorraya in a Coma (1985), the comatose main character, a little girl, waited on by a cynically detached diaspora is a figure of the country Iran.” This formula potentially applies to our little Khethiwe in Portrait of Emlanjeni. Raped by her father, the man she is named after, denied time of day before the halls of justice, but determined and learning to live, Khethiwe is the embodiment of Emlanjeni Village, and of her Ndebele people, as they navigate the institutional treacheries of identity and memory. I cannot think what literature people call this device, in both its willed and contingent performances. We will provisionally, if lazily, conspire to call it psychomimetics in this place.

Silence as an Emancipatory Response to Erasure

A dark mass of silence overcasts the community heaven Emlanjeni aspires to. Historical atrocities and disease epidemics are not mentioned by name. Vans pull up with bodies of people who die from “the disease.” “The villagers do not say its name…” Memorializing the victims of massacres carried out by a parallel unit of the Zimbabwean army under government instructions in Matebeleland between 1983 and 1987, Ngwenya says of the survivors:

These feelings are the people’s well-kept secret. They do not show them to strangers. They say nothing to them about the men, women and children who were swallowed by a moment in the country’s history, a moment that is spoken of in hushed tones. When they travel with strangers in buses or malayitsha’s vans, they look at Bhalagwe Hill, shake their heads, mumble something, shedding a tear or two before they look at their hands or laps. The harrowing memories are always there even if most of the elders who witnessed the horrendous events are gone.

The statement comes up in the course of a generalized description of a bus trip from Bulawayo, the capital of Matebeland, to Emlanjeni Village. There is a growing body of literature on the massacres, infamously described as “a moment of madness” by then Zimbabwean president Robert Mugabe. Novuyo Rosa Tshuma, NoViolet Bulawayo and Christopher Mlalazi are among the more recent writers to write on Zimbabwe’s “original sin,” whereby an estimated 20 000 people, mostly civilians, were killed on government instructions.

Hard upon this elegy to silence is a reproach to treacherous historians. The silent witnesses are favored over career-minded writers as faithful guardians of memory:

Memory has legs. Even when the treacherous pens of dubious historians deceptively omit facts, memory creeps in the underbrush of people’s minds, whispering, sighing, popping its head on the surfaces of their amnesia.

We find here a conundrum where silence faithfully captures what words are aimed at erasing. Or, perhaps, the author is only comparing the silence of the writers with the silence of the witnesses. For the writer of erasure, it may be that words are willed deception. In Percival Everett’s Erasure (2001), newly adapted into the movie, American Fiction (2023), the novel within a novel is a parody of stuck-up verbiage pretending to ghetto authenticity. For the silent witness, words could already be inadequate to the problem of memory. Sightings of history from the bus window are immediately complicated, in the following chapter, by the rape of Khethiwe – if the singular tragedy the girl suffers at the hands of her father can be taken to symbolize the loss Emlanjeni village and its neighbors now lives with following the state-sanctioned massacres.

The violence of rape is internalized by the survivor’s self-probing of their presumed participation in it. Hormonal reflexes in the moment of violation, and the possible fact of a pregnancy, means the memory of rape may never be a clearly categorized “him vs me,” but a memory that coincides with internalized violence, distorted complicity and self-hate. In the case of little Khethiwe, the evil is existentially twisted by the fact of the criminal being her father. It is not just the question of memory, then, forking into fear and loathing but also that of identity. Is a man who rapes his daughter still her father? Does he not unfather himself through a taboo that is, by nature, an inhumanity? And the filial rape survivor? Is she not to ask with hysteric Juliet, “Why am I that name?” What about the state that massacres its citizens?

The default attitude to civic disquiet – at least from the emancipatory angle – is to speak up. Stanley Nyamfukudza’s essay, “To Skin a Skunk: Some observations on Zimbabwe’s intellectual development,” disapprovingly historicizes a feature of Zimbabwean politics, idiomatized in the title, whereby few people “detach themselves from the larger group to talk over a matter, which […] may not be politic to discuss in public.” Regarding the matter at hand, there has been no shortage of public discourse. Only, the motives of the speakers have been, sometimes, put to question. The subject of the massacres might, indeed, be messier than the usual dichotomy between speaking up and broaching the uncomfortable. Living in Bulawayo, the capital of Matebeland, I have read articles cautioning eminent meddlers from neighboring regions against dyeing their indigo a deeper hue than the bereaved, and especially not to reduce an unresolved national tragedy into an election platform. Back in Harare, two friends who could not have been born at the time of the atrocities have intimated same.

For residents of Ngwenya’s Emlanjeni, silence is mourning. In the embrace of silence, memory is a psychic charge that words can only contaminate. But writing silence is a slippery gesture, perhaps, even a Derridian conundrum. It is an unusual thing to suggest but perhaps true that the writer is performing silence as an emancipatory gesture. In a video interview, Ngwenya’s interlocutor and editor, Dr Chidora, approvingly contrasts her from post-2000 writerly contemporaries whom, he says, have failed to divorce themselves from politics. “When I read Emlanjeni, even in the background politics was not there. It was as if you abstracted that village from this concrete reality of Zimbabwe.” Perhaps, off willed abstinence from the Mugabe-ism and NGO-schism of the Zimbabwe discourse, Ngwenya creates an idyllic parallel universe with Emlanjeni. She explains a motive she had for the novel in the interview with Dr Chidora:

I wanted to remind them (urbanites or, maybe, political elites) to say, “Look! Life is not all about you and your politics in this country. There are other things that are happening in this country which don’t have anything to do with politics.” Like the village of Emlanjeni… they live their life like they lived back then, without any interference or pollution – I will call it pollution. You will never hear of a meeting, like a donor’s meeting, in Emlanjeni Village. People manage their affairs.

Rare is a novelist who can release words from themselves to their pure potentiality. We faced with a focused silence (for what has been removed from it) that, with Jacques Lacan’s purloined letter, nevertheless arrives at its destination. This is something of what Ngwenya achieves with Portrait of Emlanjeni.

A Memo to Womankind

At its core, Portrait of Emlanjeni is a novel about learning to live. We have suggested that Khethiwe could be the embodiment of her village, not least for her resilience and love of life. We find in her, the unbreakable spirit of a people to whom everything has really happened. Her struggle is paralleled by that of her friend Zanele, who falls pregnant to a ne’er-do-well in high school, raises her head, gets some help and finds herself beyond the ostracism she initially faces. The novelist is invested in these precarious lives and sees something of herself in them. Per Ngwenya:

I have been knocked down so many times but I always ignite and rise; I rise to rewrite the game and the rules with a smile. My female characters are like me, I am in Khethiwe, Zanele, Nonceba and others. Those women who do not settle for what they do not deserve. They know their worth. One more suggestion, to make it more of autocriticism than autobiography. Would you consider saying, ‘Because of purpose in my soul, I am an old soul. I feel like a force of nature, I have been knocked down so many times but I always ignite and rise, I rise to rewrite the game and the rules with a smile. My female characters are like me, I am in Khethiwe, Zanele, Nonceba and others. Those are women who do not settle for what they do not deserve. They know their worth. Nobody can easily break them, the world should rise to meet them or get out of their way.

The Soil Fights Back – Customary Justice vs State Justice

If we consider – let’s say, beneath the vastly diverting vistas of Ngwen.ya’s conjuring of place – the observation that “Emlanjeni village is, itself, the main character,” we find that a village is its soil. And, of course, a village is also its people. In the situation under consideration, this difference means nothing. “Those of the soil,” for example, is an idiom we use to refer to the ancestors. It is also a, less common but not unheard of, reference to the disempowered. Again, a difference that means nothing in our current situation. In Emlanjeni village, a wobbly balance of life is worked out in which a people live by the customs of its ancestors; the weak enjoy sacredness of place while the living and the fallen mutually wait on each other. When state sanctioned-justice fails, it is the soil that fights back!

Portrait of Emlanjeni is, in some important ways, a comparative study of the African customary justice system versus the European law as adopted by the modern African state. The novelist takes up two cases that seem to work differently in the African (village) court and in the European (or modern African) court. In both instances, the soil fights as its ways of fighting back. At the denouement of the first scenario, we gasp with delayed gratification at the exacting of poetic justice. In the second instance, it might seem as though the soil’s kind of justice is prosaic this time, fixed like the paper justice of the modern halls.

Let us look at the basic outlines of both cases. The first case – largely the one that drives the story of the novel – concerns the rape of Khethiwe. Looking out for the unfortunate girl, the village cleaves religiously to the old understanding that a child is everyone’s child. Two police officers arrive in Emlanjeni to find Sibanda, the rapist-father, tied to a tree but, of course, warns the villager to “leave him alone until he had been proven guilty.” At the courts, the moral verdict of the village women who travel together to look out for their girl is inadmissible. Evidence is all.

Sibanda’s rape of his child, while his lastborn daughter looks on, is something of a family secret going back to his own father and, therefore, to his sisters. A crime against both nature and culture, to revisit Claude Levi Strauss’s incest teaser. Not so much a crime against the law, perhaps, because it is committed with attention to detail. Having wrapped the law around his little finger, Sibanda thinks to fortify himself against nature (or, is it culture?) with witching rituals. In a poetic turn of justice, the rapist-father makes a nocturnal misstep, gets caught in an act of witchcraft, having haplessly targeted the village head for taking up his daughter’s cause against him. He is tied to a tree – again! – “naked to the bone.” Shame or no shame, Sibanda is really bound to leave the village this time. He has been retried in the court of nature, as it were, with the tree symbolically coming back from the first incident. The soil has fought back.

It’s the soil’s second revenge that gives off touches of prosaic justice. In fact, the soil’s business in the matter is rationalized from a scripture reading of Cain and Abel, although the appeasement of the fallen is also an age-old custom in the village. In this second case study, Ncube provocatively trespasses his neighbor, Dube’s, compound, and misses him with an axe, falling on the rod in Dube’s hand in the course of a second attack. On the strength of witness testimonies, Dube is dully cleared by the courts. Ncube died on his own sword, per adage, full stop! But this does not stop an endless line of Dube’s family members, immediate or extended, from dying or catching madness at the hands of, yes, the soil.

Dube is fined a cow at the chief’s court to escape spiritual retribution for the accidental murder but argues that the High Court cleared him. “This court thing deceived him but his family is perishing,” counters one sympathizer. “He should just go and pay compensation. In the Bible, Abel’s blood cried to God against his brother Cain who had killed him. Spiritually, killing cannot be excused,” says another. When an evil wind comes to seek the audience of a family, there is simply no beating it back. But it may be deferred. So, Dube visits Sibanda, the rapist-father, for self-protection rituals. The justice of the soil is blind. As much as state law’s regime of evidence gets it right this time, the soil wants nothing less than the balance of life. Alas, the community’s old laws play ceremonial fiddle to the inherited Western justice system! I deal with this colonial impotence at length in a previous review of the novel.

Totem and Taboo – A Dark Pastoral

Emlanjeni by bus, dry soil and acacia, prime the reader for sightings of hunger, death and silence. The remains of colonial patriarch Cecil John Rhodes, nicknamed Umlamlankunzi, look down the sacred mountain while children of the soil, victims of a massacre, are scattered in the mine dump. Silence presides over the ceremony of death. From a dry place “cleaned by nature’s maids” as it were, the Bhalagwe Mine dump issues “silent drumbeats” that evade nature’s obstructions to find their way into the hearts of Emlanjeni villagers. One burial is an unnatural totem, erstwhile godfather of the country, while the other burial is a taboo, best left unsaid.

The hill itself looks tormented. It seems to be yearning for forgiveness, for relief, for freedom. Its folds contain a dark history, a burden that a simple hill cannot carry alone. Yet sometimes it seems to be blaming the irresponsive, incurious, insensitive dump lying at its feet.

Of contemporary tragedies people would rather not talk about in the novel, it is almost as if violent death during police chases and death from the disease are an accepted feature of the village economy. Those who are most exposed are the enterprising youths responsible for giving the village the little life left in it… by leaving it! As if the only life still available to the village is to be accessed by those who are prepared to pass through death. Ultimately, Emlanjeni Village is a testament of learning to live. The survivor, Khethiwe, stands for a people that has chosen itself over its misfortunes.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions