You know those little circles when a bobber drops in the lake? They’re small at first then they move out further and further, getting so big and I never knew where exactly they went. All the way to the shores, perhaps.

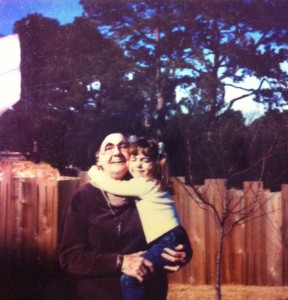

My Nana liked to fish. She used a bobber now and then hunting for bream or catfish, maybe, but she preferred bass fishing. And she had

the shiniest fanciest lures you’ve ever seen. Nearly as ostentatious as the braided gold necklaces and jeweled costume brooches she liked to wear. The lures where big and silvery with red bug eyes and so many claw hooks hanging from front to back. Dang! It hurts to get one in your finger. Their bellies sawed in half so they wiggle when you pull on the line. I like the way it feels when they fly and flop in the water. But I never was any good at catching fish. Nana was. Even well into her nineties she could cast just so the bait would land next to the huge fallen branch by the shoreline without getting caught hardly ever. And she’d reel it in slow, but not too slow. With the same effortless deliberation that she dealt cards. Of course she wasn’t so patient if they weren’t biting. If I was having luck she’d poach my spot. And if she saw some schooling across the lake, she’d power up that trolling motor before I had a chance to finish reeling in my last cast. A real fisherwoman. An Alabama-accented fisherwoman who wore visors, “sunshades” and lipstick. A real shark at bridge, too.

Born in 1899, Mary Susan Caton was smack in the middle of eleven children. She always said she grew up “waitin’ on the older ones and tendin’ to the younger ones.” She told me all the stories, late at night, laying in my wrought iron bed. I’d say, tell me about the “olden days,” Nana, and she would. My own personal Laura Ingalls Wilder. She told me about the time a tornado came and tore down the one-room schoolhouse in her home town of Andalusia, Alabama. She told me what it was like to ride in a buggy, and about the Christmas her brother caught on fire because they all got new flannel pajamas and he stood too close to the hearth. Or about the time she cropped her hair and her husband was so mad he made her leave her hat on inside despite the heat. When we stayed at her cabin in Crockett, TX, she’d wake up singing, banging pots and pans too early so as not to let you sleep in, “Wake up Jacob, mornin’s a breaking, peas in the pot and hoe cakes a bakin.”

She’d cook the bacon in a Pyrex in the oven. Nobody likes it that way, all soft, but it was easy and you could make a lot at once. Did the same thing to fry eggs. I was well into my twenties before I realize that most people don’t baste their eggs in bacon grease. And my how she loved her coffee. When she said it, it sounded like “cahwfeh.” “Sugah, woudja fetch me some cahwfeh?”

She nearly died from her second bout with Colon cancer when she was 101. After outliving both her children, her husband and friends, I think she had come to believe it was her god-given duty to keep on living, whether she liked it or not. Insisting on having the surgery, she fell into a coma after the cancer was removed. Wouldn’t wake up for days, looked so dead laying in the ICU. My Momma kept telling the nurses, just give her some coffee. Put it to her lips. It’ll wake her up, she loves her coffee. They finally did it and sure enough. She lived two more years.

Died on Good Friday, 2002. She had lived in three centuries. A fact she was most proud of, although her mind was pretty gone there at the end and she liked to tell people that she was 137 years old.

Mary Caton Lingold studies literature at Duke University, Durham, NC.

Photo Credit: Mary Caton Lingold

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions