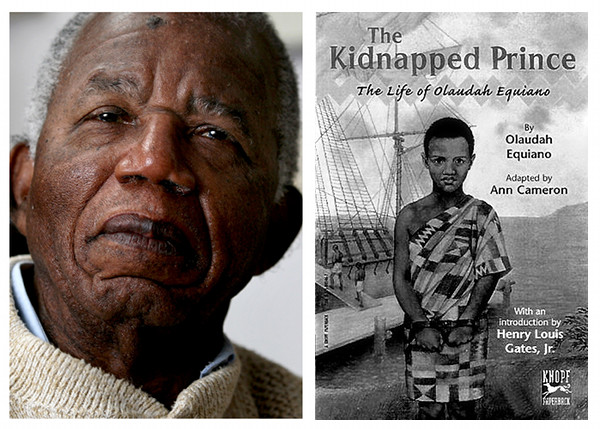

“[PBS Television] came to me and said, What would the village have done the day they discovered that the boy (Equiano) was missing? — Chinua Achebe

In the late 90s, Achebe tried to imagine the African experience of loss and slavery. As part of a show, PBS asked him to reflect on how an African family or village might have mourned the loss of a loved one who had fallen victim to slave raiders. I find his comments interesting. You may not know this, but Achebe happens to be the right person person to ask such a question. He has distinguished himself as the kind of thinker who believes in the political and ethical significance of confronting the past no matter how dark it may be. If you’ve paid close attention to the controversies surrounding the publication of his recent book on the Biafra War, you’ll realize that the question: “What would the village have done the day they discovered that the boy (Equiano) was missing?” –is a question that Achebe would take very seriously. Here is what he says:

“[PBS Television] came to me and said, What would the village have done the day they discovered that the boy (Equiano) was missing? So I said, Well, I am not really sure, but certainly there is a dirge that my people sing when a young person dies suddenly. Members of his (or her) age group (traditionally) would enact a ritual of looking for him (or her!). The idea is that this cannot be true, this person cannot be dead. He…is playing a joke. It’s play. It cannot be true, it cannot be serious, and so we will find him. Perhaps he has gone into the stream to fetch water, perhaps he’s gone to the market, perhaps he’s gone to the farm, or whatever, but he’ll be back. He’s just playing with us. So they go around the village calling for him. And the refrain, the word, the sound, that occurs again and again nzomalizo, which is just a made-up word, but the kernel of it is zo, which means hide. And when you put mali on it, it is like joining playing to hiding, like a children’s game. So they sing this song, calling on the person to come out of hiding. And so I speculated that they (Equiano’s age-mates) may have done that back then, for him. You don’t sing this song for old people whose time is up. They have fulfilled their time. You don’t do it for babies; babies don’t have age-mates who can go around the village singing. It’s for young adults. That’s the song I sang. But then … I had written a poem with this idea for an age-mate of mine who had been killed in the Biafran war, Christopher Okigbo, who was a very fine poet-in my mind, perhaps, the finest poet of our generation; and I had written a poem in Igbo for him, using this idea; and it was that poem (for Christopher Okigbo) that was, in fact, the origin of the poem that I then transferred to Equiano. Instead of naming Christopher Okigbo [on the television program], I used this same dirge for Equiano because it seemed appropriate. So, that is the background, [laughing] a longish background.”

But is Achebe right? Is losing a child to death the same thing as losing a child to slavery? Is a dead child the same as a stolen child? Are both kinds of pain equivalent? So would both forms of loss be mourned similarly? I may be wrong, but slavery is not death. It’s more bizarre than death. How does a parent, a wife, family live with that type of loss? I really don’t know, and I have a feeling that Achebe is having difficulty imagining what sort of loss slavery is. At least, Achebe is honest about the fact that he doesn’t have the answer. Do you?

The excerpt is from:

THE EPIC IMAGINATION: A Conversation with Chinua Achebe

R. Victoria Arana

Annandale-on-Hudson

October 31, 1998

Post image via

Feature image via

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions