The Sultan had to have lost all desire for life itself. A man who marries a woman, sleeps with her, strangles her the following morning, and repeats this everyday for three years has certainly lost some vital sense of self and connection to life. This is the man for whom, like some comic book wonder woman, Scheherazade left her father’s house. She wanted to save the Sultan not because she loved him—who could love such a villain—she wanted to save him from himself because in saving him she hoped to save herself and the kingdom, for what is a kingdom without its women?

Going into the whole thing, Scheherazade knew one thing: a man could love your body and still destroy it. She did not have the luxury that many of us do—the way we can serve up our bodies or parts of our bodies on a platter to get a man to do things. Her pretty face and stunning body were no use to the Sultan. He did not desire women. If at all he needed them, it was the way one needed trash…in the garbage.

What saved Scheherazade? Why did mad and murderous Shahryār not kill her? We know she told him stories. But why stories? Scheherazade could have danced for him, sang for him, read for him.

What saved Scheherazade? Why did mad and murderous Shahryār not kill her? We know she told him stories. But why stories? Scheherazade could have danced for him, sang for him, read for him.

First of all, stories shape the way we think by teaching us how and what to desire. A storyteller is essentially someone who manages desire by modulating the listener’s expectations with the promise of some kind of fulfillment at some future time. Stories cannot live on desires that destroy its object. Loving a story means wanting to hold on to its hold on you for as long as the storyteller decides. By telling Shahryār these stories, she taught him one thing: captivation. She taught him the simple but necessary pleasure of being enchanted, of letting oneself to be held captive by something beautiful, and never wanting to let go. She gave him the joy of waking up to a living story and not to the body of a dead girl.

For 1001 nights, she told these stories—lots of them. One story in the collection could spawn an infinite number of stories. She used all sorts of devices and tricks to endlessly string stories together. She held Shahryār captive in a mesh of unfinished stories, making him slave to endings that never came or those that even when they came left him unfulfilled and hankering for more.

Shahryār became addicted to her stories, and as with all highs, the highs had to keep getting higher. I love how she ends each story with the promise (or plea) that the next one will be more wonderful, surprising, and diverting than the last. As I flip the pages from one story to the next, egged on by this promise, I often fear for her. Will she make good on the promise?

All this for a man she did not even love and who fell in love with her stories before falling in love with her.

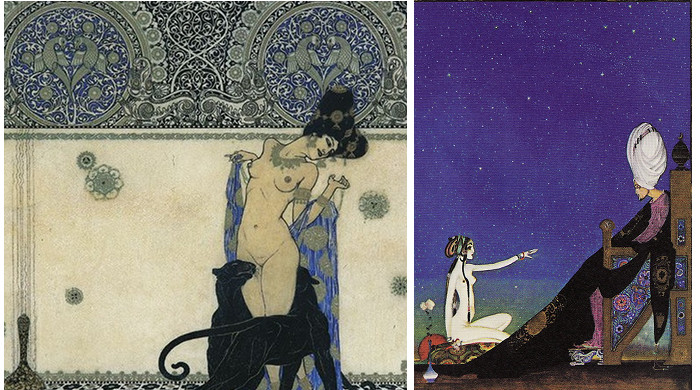

First Image: t. van gieson

Second Image: Rimsky-Korsakov’s Scheherazade

Third Image: The Blue Sultana by Léon Bakst

Episode 39: The Life and Death Importance of a Good Cliffhanger - A Case for Classics October 21, 2020 20:12

[…] The Arabian Nights: A Story Called Desire. […]