Jungle Jim is a bimonthly pulp fiction magazine based in Cape Town.

In the universe of African fiction, Jungle Jim lives on the other side of that world where people like Teju Cole and Adichie write “high” literary things that are printed, promoted, and sold expensively by big publishing houses. In this must-read interview, Jenna Bass (content editor) and Hannes Bernard (design editor) tell us how their brilliant mix of cheap paper, lurid stories, and sensational cover art is creating an innovative outlet for emerging African writers and their bizarre stories about African life and cities.

This is one hell of an interview. Illuminating and hard-hitting.

One of the most powerful moments in the interview is when both editors reflect on what it means to be white and South African and an artist.

It’s also certainly refreshing to hear industry people like Jenna and Hannes say categorically that print publishing is far from being dead or dying. You just need to know how to work the system to thrive or stay profitable.

Much love and thanks to my colleague Matthew Omelsky for asking such great questions.

Enjoy!

Matthew Omelsky: Let’s begin with the form of the pulp magazine in Africa. It seems that Jungle Jim has traces of other pop publications, like the mid-century Onitsha market pamphlets, Chimurenga, and Kwani? Do you think of JJ as part of a cohort of magazines from across the continent? What literary niche have you intended JJ to fill?

Hannes Bernard: When we started Jungle Jim, we looked into the tradition of pulp publishing in both South Africa and the wider continent, and the Onitsha market literature was definitely one of our influences. There is a distinct difference between the traditional legacy of formal ‘pulp fiction’ magazines or popular fiction, and the other magazines mentioned (Chimurenga, Kwani?), although these are presumably also influenced by the legacy of pop fiction in Africa to varying degrees. In South Africa, Afrikaans language pulp fiction, in the form of Fotoboekies (photo-comic-books) as well as other forms of international pulp were a hugely popular source of entertainment (South Africa only began limited TV broadcasts in 1976), and though pulp for black South African audiences was also prevalent, Apartheid tended to keep these markets distinct and separate. The thing that stuck with us is how often Africa (the entire continent it seems) was used to a generic placeholder for the native, exotic, adventurous and generally reinforced colonial stereotypes about Africa and Africans—something we wanted to challenge with Jungle Jim.

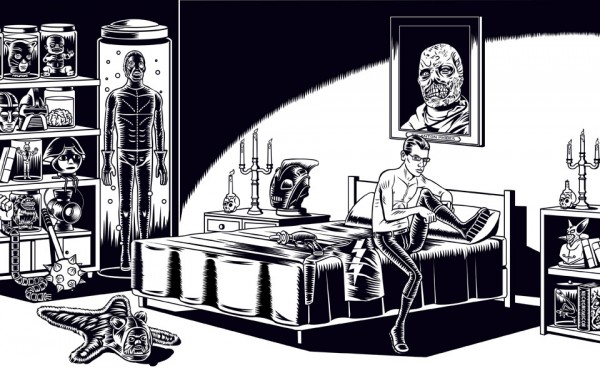

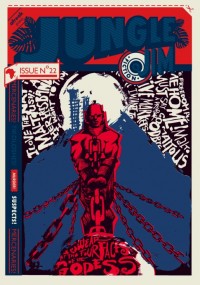

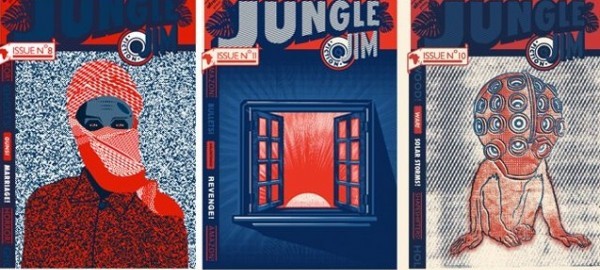

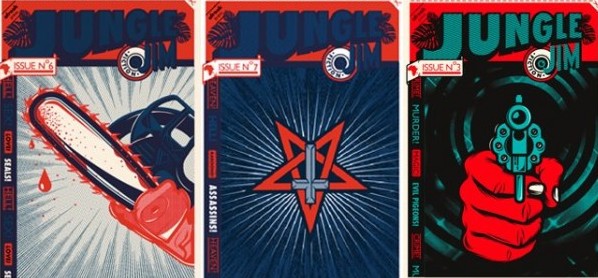

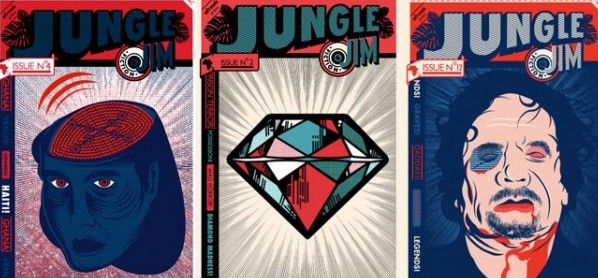

Omelsky: The design of the magazine is distinctive. How do you understand the relationship between the text and the magazine’s scattered, often haunting, black and white images? Do you think of the cover art and design as a kind of reworking of the early 20th century pulp magazine aesthetic?

Hannes Bernard: Yes and No. The design of Jungle Jim is based on an honest pulp-production strategy more than anything else—producing the most impact for the least amount of money. For us the single most important aspect of creating the magazine was the ability to continue frequent production (twice a month) while having literally zero budget (other than the spare change in our pockets at the end of each month).

Starting with the absolute cheapest production method we could find, we designed a format that would deliver as much colour, impact and tactile value as possible.

This is a classic pulp design strategy, and we believe one of its greatest appeals—giving readers a tactile, visual and engaging experience far more valuable than the cover price.

The current format allows us to produce 4 stories per issues (along with a 3-colour cover and back cover, two 3-colour illustrations and four 1-colour illustrations) while still selling for a profit at $1.50US per issue. This economy, in both dramatic storytelling and visual design, is inherent to pulp publishing, but it also allows us to extend our imagery beyond the existing canons of traditional, Africa-themed pulp fiction. We are often asked if Jungle Jim is engaging with some sentimental or nostalgic aesthetic, but the truth is that most of our collaborators are contemporary African illustrators whose work (if produced in a different format/technique) would have no reference to pulp aesthetics per se. So it seems the limited/economic production techniques renders Jungle Jim invariably retro, whether intentionally or not.

Omelsky: Many of the stories throughout the issues of Jungle Jim have elements of what might be called “African noir” fiction. Detective stories, murders, corpses, criminal organizations. Could you speak some on the noir elements in Jungle Jim, and more broadly, to the seemingly newfound place of the detective story in contemporary Africa?

Hannes Bernard: While Jungle Jim deals in a wide range of genres (horror, romance, noir, sci-fi, fantasy, true-life and variations thereof) we find African noir particularly fresh and inventive. One of the most frequent debates we have regarding submissions is whether a story can really be called ‘pulp’ or genre-fiction. While we limit ourselves to these genres, we’ve also allowed a lot of leeway in how we interpret such classifications. We were never interested in recreating the ‘big’ detective stories, or classic narratives of international pulp from the 1950’s, 1960’s etc., but rather aimed at creating a space for contemporary genre-ish narratives from African authors. What is extremely exciting about this expanding field is the conflict of (for example) extreme violence or crime in the pulp tradition, but originating from places in Africa where extreme violence and crime are daily realities. This inversion in the agency of Africa as not merely a passive location or placeholder for danger, adventure and crime is at the core what we love about Jungle Jim’s noir contributors. The conflict between dramatic, visual storytelling and the African context creates an engrossing experience beyond the essential escapism inherent to popular and entertaining forms of fiction, and Noir stories seem extremely adept at dealing with these conflicts. We have also just been lucky in receiving so many well-written and engaging African noirs.

Jenna Bass: It’s also good to note the distinction between the detective/crime genre and the sub-genre of noir—though of course there is much overlap. But noir in particular is characterized by a nihilism, a cynicism, ambivalence, and critical social eye which is exceptionally interesting in an African context, with its perceptions, both home-grown and imported, of negativity, political uncertainty and impending doom.

Omelsky: Another key element of noir fiction is the labyrinthine city, which constantly surfaces in Jungle Jim. So many of the stories are set in bustling cities like Johannesburg, Lagos, and Accra. In a way, many of the stories almost seem to map out the informal spaces of the African city – slums, squatter camps, townships, locations outside the formal rule of law. Do you envision JJ as a certain kind of chronicle of the modern African metropolis?

Hannes Bernard: Yes! For both Jenna and myself Jungle Jim is a way to expand our own experiences of the wider continent. It’s unfortunate that although Africa is such an incredibly broad and diverse place, our cultures remain (for many reasons: historical, political, economic, linguistic) largely insular. We simply do not know enough about each other! We are as much a victim of the ‘generic Africa’, ‘heart of darkness’ legacy as everyone else. What is extremely exciting about reading stories set in Lagos or Accra or any other metropolis is that we can also immediately relate to these chaotic scenes (despite the unique characteristics of each city) as we share those common experiences to some degree. (Though Cape Town is certainly a tranquil fishing village in comparison to Lagos!) Even on a local level, in South Africa, where we are still dealing with massively segregated communities, these narratives give us access to some common urban geography.

Omelsky: Many of the contributions to Jungle Jim could be categorized as science fiction, including the terrific issue devoted to South African SF. Why do you think South Africa has had so much more of a footing in SF than the rest of Africa?

Hannes Bass: I’m not sure if its possible to state things so explicitly, simply because we do not know all that much about Sci-Fi in the rest of Africa. We have been surprised (on more than a couple of occasions) by the quality of Sci-Fi from different parts of the continent. During the heyday of pulp, there were many sci-fi stories coming out of places like Egypt for example. (We keep a catalogue of traditional pulp cover on our website and Facebook page, and try to find as many non-Western examples as possible).

That being said, the local publishing scene in South Africa does seem to be more developed in some ways, and this has led to the establishment of wider niche or genre markets locally (in many genres, sci-fi included).

Another major (and often overlooked) aspect has been the major impact of Neil Blomkamp’s films (District 9, and now Elysium), which introduced novel sci-fi narratives that combine extremely vernacular cultural aesthetics and South African history and characters, to a worldwide audience.

This realisation—that Africa can produce high quality, original, engaging and internationally popular sci-fi that can compete with Hollywood’s best—has made many people aware of this untapped resource.

Jenna Bass: It also depends on whether one is talking Science Fiction or Speculative Fiction—again, a much-debated boundary. It seems to us that speculative fiction and fantasy have a strong tradition elsewhere on the continent—especially in the immensely rich literary scene in Nigeria. But science fiction does perhaps have a bigger community in South Africa (to my knowledge at least), perhaps due to our ingrained ties and aspirations to American and British culture, to which we are, to some extent, still beholden, depending on where you’re looking. What could rather be said is that South African SF/Fantasy communities are maybe more tied down by specific genre tropes, so our genre writing is more recognizable as such—perhaps unfortunately. Having said that, there appears to be a great Science fiction following in Egypt—and we recently published an extract from a highly successful Sci-Fi novel by Ahmed Khalid Towfik titled Utopia

Omelsky: There have been some fantastic South African SF writers, the majority of whom are, and historically have been, white. Could you perhaps reflect on possible linkages between what it means to be white in South Africa and on the continent and the genre of science fiction?

Hannes Bernard: Wow, I’m not sure…. I think we can agree that there is a historic link between whiteness and the ability to publish (or at least access to publishing platforms) in South Africa, as a result of Apartheid and its legacies. Simply put, generations before us placed vast resources in developing cultural spaces for white South African voices, while black publishing was often left to fend for itself (with great success by some, such as DRUM magazine). As I mentioned before there were also many black pulp-fiction publications back in the day, but those tended to be of the ‘made-for-black-Africans’ variety, with white producers largely in control.

This is a really tough question to answer, since so many aspects of contemporary culture in SA are still cast within the ranks of specific race/cultural groups. Even whiteness in South Africa is not a homogenous class (specifically since we have both English, i.e. British colonial influence, and Afrikaans, ie. Dutch colonial influences). Maybe we should just clarify our positions? Jenna is an English speaking South Africa, and I am Afrikaans, and in some ways we still need to speak from our own experiences, as frustrating as that is. What I can say is that there has been a massive change in the identity of young Afrikaans South Africans, especially in Cape Town, and especially those working in so-called creative fields. While we grew up in the last years of Apartheid, for many of us our teenage years (naturally angst-ridden) were compounded with a kind of identity schism.

Overnight the rules of citizenship changed (or at least what citizenship meant), and the aspects of European enlightenment that fueled so much Afrikaans Apartheid rhetoric came crashing down, and suddenly we saw ourselves as the offspring of racists, bigots or worse. This was particularly difficult for those young Afrikaans writers, artists, creators etc. who not only faced further alienation from the majority of the country (as previously entitled White masters), but also from within our largely conservative communities, who often still espoused Apartheid sentiments or at least mentalities.

I think this alienation (from both a wider national identity, as well as close communities), especially during such formative years, is a strong driving force for imaginative (i.e. Alternative) realities. I guess this can be considered purely as a need for some form of escapism, but in the case of South Africa I think there are other aspects and archetypes in sci-fi conventions that we can relate to on a local level—overarching, hegemonic power-structures, universalist good vs. evil, the fight for individual liberation against a bigger, organized, overlord etc. Many people still suppose that sci-fi is somehow out of place in Africa, and I think this is largely because Africa is not generally seen as a place of technological advances, which is of course nonsense. While I’m hesitant to attribute any concrete links here between whiteness and sci-fi writing (other than the historic advantages of being white in SA), I think we’re simply approaching a time of new possibilities for writers in South Africa, black or white, and we are less inclined to reinforce the notion that somehow engaging sci-fi (or any other genre for that matter) has to be constructed according to Western standards… but again, I’m saying this as a white, Afrikaans South Africa.

Jenna Bass: I would refer back to the possibility that South African Sci-Fi, especially by white writers, is often simply just more recognizable as Sci-Fi. It comes from writers who have long been immersed in the genre and niche, and have a frequently American or British infused perspective thereon. There is still a lot of respect for the conventions, which is maybe in some ways less prevalent among writers elsewhere on the continent. But this is I’m sure a gross generalization, and we have fine Sci-Fi writers who are definitely creating new takes on the genre.

Omelsky: By way of conclusion, what role does Jungle Jim and other popular lit magazines play in shaping this idea of “genre fiction” in contemporary Africa? Why is it important for small publications to help carve out emerging African genres like crime fiction and science fiction?

Hannes Bernard: Some of this is touched on in the previous questions, but for us its really about proclaiming the possibilities that exist right now for publishing the things you want to consume yourself. When Jenna and I started Jungle Jim, we (as in the global collective of writers, publishers, designers etc.) were already entertaining the idea that physical publishing (especially something like pulp) is dead or dying. So starting a niche, printed magazine seemed somehow counterintuitive to the times. Of course it turns out that people are not necessarily reading less, but rather that people are reading differently. The convergence of many technologies (internet, riso printing, international banking etc.) made the barrier of entry for something like Jungle Jim extremely low. I’ve always seen this as the panacea for this print-is-dead mentality. Doing something like Jungle Jim even 5 years ago would have been a lot more challenging, and 10 years ago it would have been a vastly more difficult endeavor for even the bigger publishing houses.

In many ways those bigger publishing companies are still in a challenging position, since their revenue models are reliant on either outdated strategies, or are limited to publishing only one certain kind of thing, and everything outside of those fiscal/market constraints implies big risk.

Even in the spheres of online publishing (ebooks, essentially), its more difficult for these publishers since they now have to compete with an audience who read far more, but from a multitude of sources through an infinite number of genres, styles etc.—everything from comments on a news article, to Harry Potter fan fiction forums. I see these forms of divergent media consumption as far more closely modeled on the tradition of reading as popular entertainment (as apposed to the more narrow and formalized classes imposed by big publishing, i.e. the high literature novel, the holiday trash fiction, the travel book, the non-fiction resources, etc. etc. etc.).

Ultimately I think there is a far bigger audience for popular, entertaining fiction than most of us will concede, since we are so used to seeing the singular format—a book (or the occasional literary journal which invariably attracts a particular class of reader.) Historically we have been very reliant on larger establishments to produce our fiction, and this is something that is luckily changing very rapidly, and is of great importance in Africa. In many ways our so-called lack of development is our biggest asset. In many parts of this continent the cultural sphere is not yet dominated by western media interests. This, coupled with the low barrier of entry into publishing today, can enable many people to start producing, collaborating and distributing their own entertainment. We have the possibilities today to define Africa the way we want to, and we can do it at almost at no cost!

Images from Jungle Jim Facebook Page

**********************************

Matthew Omelsky is a graduate student in English at Duke University, where he works on African novels, science fiction, and experimental film. Read Matt’s review of AfroSF HERE.

Matthew Omelsky is a graduate student in English at Duke University, where he works on African novels, science fiction, and experimental film. Read Matt’s review of AfroSF HERE.

Issue 22 of Jungle Jim is out. Order HERE.

Academia and the Advance of African Science Fiction | omenana March 10, 2015 06:20

[…] Omelsky, M. (2013b) ‘Chronicling the African Metropolis: Q & A with ‘Jungle Jim’, South African genre magazine’. http://brittlepaper.com/2013/10/chronicling-african-metropolis-qa-jungle-jim-south-african-pulp-fict… […]