A while back, David Evans and I had a Twitter conversation. Somewhere along the line I recommended Chaka, a historical novel by Thomas Mofolo. Evans read it and wrote the review posted below.

Evans, a World Bank economist, is the most avid reader you’d ever meet. He is a fan of African novels and writes a blog where he says smart things them.

Really loving David’s review. It’s both fun to read and clever!

Enjoy!

****************

When the first page of a novel warns, “Before we plunge into our story, we should describe how the nations were settled in the beginning,” my heart sinks. How long before I’ll get to the action? In the case of Thomas Mofolo‘s Chaka, not long. Within 25 pages, there’s a forbidden love affair, a battle over kingship, a young boy killing a lion, a magical medicine to guarantee victory in battle, and — worth the 25-page wait — a giant snake that emerges from a river, wraps itself around a bather, and proclaims a prophesy of Chaka’s future. Later in the novel, we see cannibalism, matricide, consultations with the dead, and treachery. We also see a super hot king: “Even on the battlefield his men, when wounded and about to die, would request the king, as their last wish, to disrobe so that they might admire his body for the last time, and thus die in peace; and he would, indeed, do as they asked.”

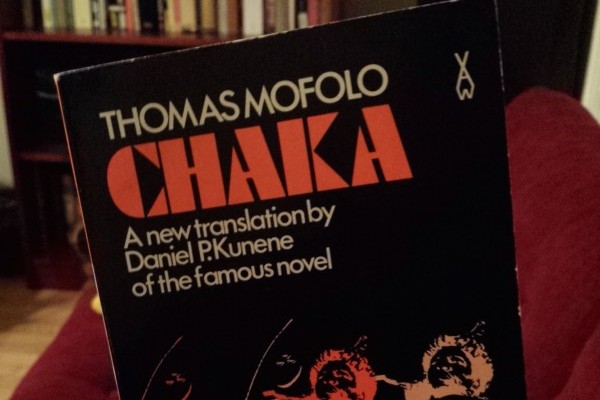

In this early example of Lesotho’s literature, written in Sesotho in 1910, published in 1925, and translated to English in 1931, Mofolo weaves a fantastical tale, based loosely on the life of the great Zulu king Chaka (or Shaka), who lived from 1787 to 1828. I read a later translation, by Daniel Kunene in 1981. While the language of the book took me a bit of work to get through, it wasn’t for lack of action. Chaka has an insatiable thirst for power. Mofolo shows the origin and the price of that thirst. Here’s what I learned from Chaka.

Ten Life Lessons from Chaka

1. If you don’t like to share, there’s always gossip: “Gossip is not like bread, so no one withholds it from another.”

2. How to get people to believe you’re a prophet: At one point, Chaka is missing, and while most agree that he is gone forever, “one of the diviners affirmed with an oath…that Chaka was alive.” When Chaka appears people speak of the doctor, “So-and-so could never be wrong!” As Kaushik Basu put it, “To be known as an expert, keep making extreme forecasts. By the laws of probability you’ll be right once. Then don’t let anyone forget it.”

3. Just do it: “When he [Chaka] saw that no one was going [to capture the dangerous madman], he got up and went.”

4. Take the high road. Wait a while after someone dies before making a grab for the kingship. A patron tells Chaka: “Don’t be in a hurry, you are still going to stay another six months here with me, so that you may not profane your father’s death by contesting the kingship by war so shortly after his death, with his corpse still warm in the grave.”

5. The bad sensei in the Karate Kid was right when he taught “We do not train to be merciful here. Mercy is for the weak.” Or, as Chaka is taught, “Mercy devours its owner.”

6. Cattle bring peace: “A head of cattle is a great uniter of people.”

7. Confirmation bias applies to the divine origin of kings: When Chaka’s messengers claim that Chaka is sent from God, “their statements were easily believed, because those thoughts were already there in the hearts of the people.”

8. Think now so you don’t regret later: “It is necessary that a person should understand what he is doing while there is still time, so that he should not afterwards regret when regret is of no further use.”

9. If you want to be king, you need stick-to-itiveness: “A king ought not to be fickle and change his mind from one day to another.”

10. Finally, you may in fact be able to take it with you (depending on what “it” is): “Everything a person does in this world the sun takes with it when it sets and carries it to that great land of the living who you regard as dead; and all these things will wait for him there, growing and increasing like cows which calve repeatedly.” (Note the cows reference, bringing us back to #6.)

Visit David’s blog Read African Writers and follow him on twitter @tukopamoja.

David Evans Reviews Chaka by Thomas Mofolo | Books LIVE September 02, 2015 07:56

[…] Complete review in Brittle Paper […]