Each day brings us closer to July 4th when the 17th winner of the Caine Prize for African Writing will be unveiled.

You’ve either read the shortlisted stories or read the reviews we posted right here on Brittle Paper. You have a sense of what the stories are about. You know whether you like them or not. You have your favorites, who you’d like to win, and so on. Well, it’s now time to shift focus from the stories to the brilliant minds that concocted them.

We knew this time would come, so while you were getting acquainted with the stories, we were busy interviewing each of the shortlisted authors. We wanted you to see a side of these writers that you didn’t get from reading their stories. Here is the second interview in the series of five. We would like to thank Nairobi-based writer Akati Khasiani for fielding the questions.

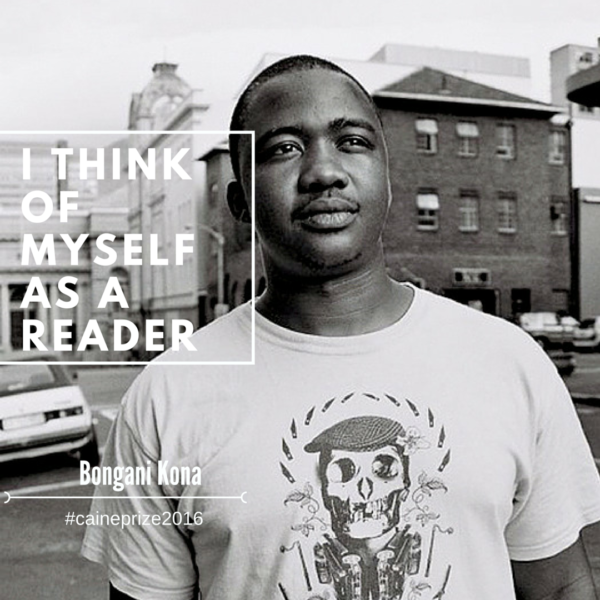

Bongani Kona is a Zimbabwean writer. His shortlisted work is a story titled “At Your Requiem.” Bongani is currently in a creative writing Masters program at the University of Cape Town.

“At Your Requiem” was reviewed by Aaron Bady who praised the unusual logic of storytelling at the heart of the narrative. [read here if you missed it]

Enjoy reading!

***

Congrats on making the Caine Prize shortlist. How is being shortlisted significant for you?

Thank you. It’s an incredible honour, and I’m really grateful. I think the thing most aspiring writers need, and I count myself as one, is encouragement. That’s the most significant thing for me—the encouragement to keep trying.

The prize is awarded for outstanding “African writing.” We are curious about what ‘African writing’ means to you? Let’s be the first to agree with you that it is an old and tired question. But we are hoping that you’ll humour us and take it as a chance to reflect on the modifier “African” and, perhaps, its place within your work and your sense of yourself as a writer.

To be honest I don’t how well I’ll be able to answer that question or if I’ll ever be able to answer it. I think of myself as a reader and when I was in school the phrase ‘African writing’ almost always referred to fiction in English from south of the Sahara. Never non-fiction or any of the other forms of writing. So I’m keenly aware of the gaps in my own reading, and it’s from that position that I’m trying to answer that question for myself.

What’s most important to you in the crafting process? The theme/subject/topic of the story or the form/experimentation/aesthetics of storytelling?

There’s a line from a short story by Lorrie Moore, which goes something like “I don’t have talent I have willingness.” I really like that because I’m a beginner when it comes to writing fiction. I’ve written stories, which it will be impossible to read without wincing. It’s not very good for my ego, but that’s part of the process of learning, of figuring things out. So the most important thing for me is willingness.

This year’s stories all featured characters dealing with pain in some way, whether a personal trauma or a form of societal or generational suffering. How would you account for this emphasis on suffering—given the criticism that African writing only gets consumed by a global audience when it deals with negative tropes?

I can’t speak for other people’s intentions. I can only speak about my own. I worked on “At your Requiem” for a South African short story competition in 2014, and I really didn’t think about the audience at all. I had never written a short story before, and the thing that was most important to me at the time was getting to the end. I knew if I did that, whatever the outcome, I would learn something—characterization, dialogue, setting and all of that fiction 101 stuff.

“At your Requiem” is a very heavy story, and it ends on a very dark note. What led you to conceive of this story?

The things I write almost always grow out of things I’ve read, and the spark for the story came from a poem with the same title. I don’t remember who wrote the poem, but I found it in an old copy of New Contrast, a South African literary journal. I was really moved by it, and everything else followed from there.

There is that saying—“hurt people hurt people.” Every villain in your story has a tormentor. The chain of pain and suffering in the story is left unbroken. Is there any hope for redemption?

I read somewhere online that sometimes circumstances are stronger that we are. I think that’s the case with Abraham, but for Christopher, although he may not see it that way, there’s the possibility of a different ending to his story.

There is a detached quality to Christopher’s narration. It remains very calm when retelling emotional events. Would you say your inner journalist came out in this story?

I’m not sure, perhaps, but I wasn’t conscious of it. I was trying to mimic the detached tone of a depressed person.

Does your work as a journalist influence your creative writing, or vice versa?

One of the things journalism give you is an ear for dialogue. Even if you’re writing a book review, you know instinctively which parts to pull out. I’ve found that to be useful in subsequent attempts at writing fiction. Another thing about journalism is that you have to be curious about how other people live, and that’s also really useful.

Finally, what was your favorite of the other stories?

The last time I gambled on a horse it came stone last, so I’m not trying to jinx anyone. And like I said, I’m a reader. I think all the stories are amazing. I’m just really glad I’m not contractually obliged to pick one.

Thanks to Kona for taking the time out to respond to these questions. We wish him all the best!

Click here to read more of the #caineprize2016 interviews and here to read the reviews.

***********

About the Interviewer:

Akati Khasiani is a city-bred, country-loving, Kenyan writer, doctor and soon-to-be economist with opinions and a tendency to daydream. Her work was featured in the Jalada 01 anthology.

Akati Khasiani is a city-bred, country-loving, Kenyan writer, doctor and soon-to-be economist with opinions and a tendency to daydream. Her work was featured in the Jalada 01 anthology.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions