“It means a lot, not just for me but every person who has ever believed, to every writer who is struggling and working hard to tell a story, and to the publishers who take risks on our works because they have faith. I am honoured to have shared the podium with these two amazing writers and I hope this will make other writers aspire to the best of their abilities.” — Adam Ibrahim Abubakar on winning the Nigerian Prize for Literature.

Every month, I receive at least one request to help edit a manuscript or provide a blurb for one. I also get asked to review books, movies or music CDs.

Running a PR agency, supervising a website, sabinews.com and now, keeping a full time job at ntel, means that time is no longer my friend.

But when you love literature and writing and books and music and movies, you have to make time because those are jealous mistresses.

Sometime in May 2015, Adam Abubakar Ibrahim sent me an email asking me to read his manuscript and provide a blurb. The title was Season of Crimson Blossoms

Dear TK,

Hope you and the family are doing great and that Lagos, crazy as it is, is treating you well too.

I hope you will find the time to blurb my novel manuscript as we discussed when we met. It is titled Season of Crimson Blossoms and is centered around the relationship between a 52-year-old widow and a 26 year-old political thug in a conservative Muslim community. (The MS is attached)…

A pdf copy was attached.

First thing I usually do is ask for a proof copy or a printed copy of the MS. I am a 45 year old man and reading online or off a tablet is not my default mode even though I own a kindle.

But this time all I asked was: “How much time do I have khalifa?” because I have always admired Abubakar’s writing and found him dependable. We also shared other connections — University of Jos, Civitella Ranieri, literary journalism and a love of literature.

One slow Sunday afternoon in June, seven days before my birthday, I got into bed with my kindle where I had downloaded the MS and began to read. What caught my attention first was the proverb: “No matter how far up a stone is thrown, it will certainly fall back to earth” and then I met the 52 year Hajiya Binta Zubairu.

“Hajiya Binta Zubairu was finally born at fifty-two when a dark-lipped rogue with short, spiky hair, like a field of miniscule anthills, scaled her fence and landed, boots and all, in the puddle that was her heart.

She had woken up that morning assailed by the pungent smell of roaches and sensed that something inauspicious was about to happen. It was the same feeling she had had that day, long ago, when her father had stormed in to announce that she was going to be married off to a stranger. Or the day that stranger, Zubairu, her husband for many years, had been so brazenly consumed by communal ire when he was set upon by a mob of intoxicated zealots. Or the day her first son Yaro, who had the docile face and demure disposition of her mother, was shot dead by the police. Or even the day Hureira, her intemperate daughter, had come back home crying that she had been divorced by her good-for-nothing husband.”

I kept reading even when the crick in my neck became painful and when my kindle battery ran down.

I was fascinated because I grew up in the North, first Kano and then Jos, but I was discovering something new about the North in Abubakar’s book. There was lust and passion but above all a clear-eyed exposition of what it means to be human and a woman and middle aged in Northern Nigeria riven not just by religion but by religious crises.

It was a deliciously saucy story, one that I knew would not end well but which, like a car crash on a busy highway, compels you not to look away. A sample:

“Two nights later, when he was tossing and turning on the bed next to her, she knew he would nudge her with his knee and she would have to throw her legs open. He would lift her wrapper, spit into her crotch and mount her. His callous fingers would dig into the mounds on her chest and he would bite his lower lip to prevent any moan escaping. She would count slowly under her breath, her eyes closed, of course. And somewhere between sixty and seventy – always between sixty and seventy – he would grunt, empty himself and roll off her until he was ready to go again. Zubairu was a practical man and fancied their intimacy as an exercise in conjugal frugality. It was something to be dispensed with promptly, without silly ceremonies.

She wanted it to be different. She had always wanted it to be different. And so when he nudged her that night, instead of rolling on to her back and throwing her legs apart, she rolled into him and reached for his groin. He instinctively moaned when she caressed his hardness and they both feared their first son, lying on a mattress across the room, would stir.

‘What the hell are you doing?’ The words, half-barked, half-whispered, struck her decidedly like a blow. He pinned her down and, without further rituals, lifted her wrapper. She turned her face to the wall and started counting. The tears slipped down the side of her shut eyes before she got to twenty.”

And it was different many years later when she finally makes love to another man, a younger man.

“She reached out for the wrap of suya he had bought. He had arrived at the hotel ahead of her and booked the room. But when she came, her hunger – their hunger, had been of a different sort. She had barely waited for him to close the door when she covered his lips with hers, pushing him against the panel.

Overcoming his initial surprise, he had responded with fervour, his hands reaching down to lift her dress over her head. Their tongues intertwined, their bodies entangled, their hands feeling each other’s bodies—as if to be sure that in the period of their forced abstinence they hadn’t changed— they moved to the bed. Because she wanted to, fought for it even, he let her sit astride him and ride him, her moans reaching up to the ceiling.”

Reading further, beyond the quotidian domestic routines and incipient passion, the aimless young men and bloody orgies, I heard echoes of Soyinka — “Some maniac hacked at the wall with a machete, the angry sound of metal on concrete and his hate-filled scream jarred Fa’iza’s nerves.”

As well as Gabriel Garcia Marquez in his use of prolepsis, “She had woken up that morning assailed by the pungent smell of roaches and sensed that something inauspicious was about to happen” a common trope in works of magical realism.

And so I finished the manuscript that same Sunday, all 384 pages of it and then I sent him an email:

“Best MS, sorry, book I have read in years.”

And then I sent him the blurb:

Abubakar Adam Ibrahim’ s Season of Crimson Blossoms opens as a slow paced story about a widow apparently going through a mid-life crisis then spirals into something dark and dangerous. This is a career and generation defining novel, one that captures the angst and dysfunction that is contemporary Nigerian history.

Binta’s story is Nigeria’s story all at once; a smogarsboard of pain and death told with a steady voice and sure hand. Abubakar betrays now and again his sentiments, but the story rises above it all to capture the story of a generation through the canvas of one woman’s life with all the fault lines in bold relief. This is a brave and important novel which shocks and excites in equal measure with its echoes of Marquez, Soyinka and Ben Okri. — Toni Kan, poet and novelist.

Why have I written this? First, I did not want to write a review having provided a blurb but to address the caption. Many years ago, on an online list serve I belonged to, a poet whose work I had refused to edit because I found it badly written had taken umbrage and accused me of editing and providing blurbs for ‘useless’ books. I am happy to have read and provided a blurb for Abubakar Adam Ibrahim’s ‘useless; book, Season of Crimson Blossoms.

Meanwhile, as I write this now, I wonder, was Abubakar Adam Ibrahim assailed by the pungent smell of roaches when he woke up today? I doubt it. It must have been a smell more pleasing to the nose because today something auspicious has happened. His ‘useless’ book has won Africa’s biggest literary prize.

Congrats fellow Civitellan and Josite.

**********

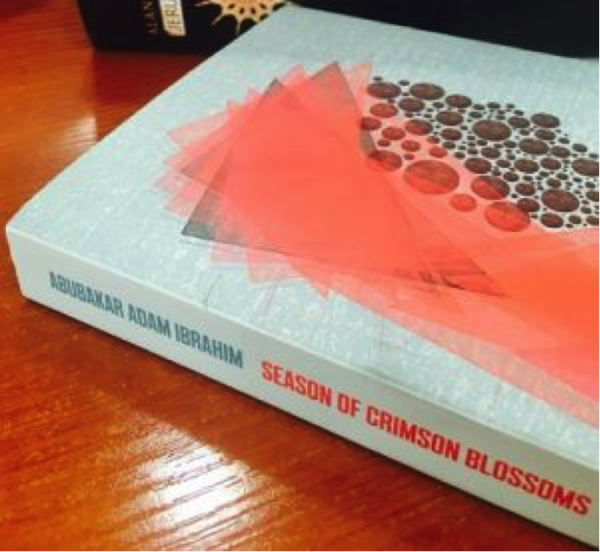

Image courtesy Abdulkareem Baba Aminu.

About the Author:

Toni Kan is a writer, editor, public relations senior management executive, and teacher. He is author of the collection of short stories, Nights of a Creaking Bed, noted for exploring themes on African sexuality, and published by Cassava Republic (Nigerian publishers of writers such as Teju Cole). He was the winner of the NDDC/Ken Saro Wiwa literature prize, awarded by the Association of Nigerian Authors (ANA), in 2009.

Toni Kan is a writer, editor, public relations senior management executive, and teacher. He is author of the collection of short stories, Nights of a Creaking Bed, noted for exploring themes on African sexuality, and published by Cassava Republic (Nigerian publishers of writers such as Teju Cole). He was the winner of the NDDC/Ken Saro Wiwa literature prize, awarded by the Association of Nigerian Authors (ANA), in 2009.

非漂 [Fēi Piāo] October 2016 Newsbriefs – Bruce Humes March 01, 2020 06:38

[…] Ibrahim, wins the 2016 Nigeria Prize for Literature, worth US$100,000. Writes author and critic Toni Kan: I was fascinated because I grew up in the North, first Kano and then Jos, but I was discovering […]