Do you ever wonder what the first generation of African writers think of African writers of today? Do the Soyinkas of the world care for the Adichies of the world? Can the Things Fall Apart generation see anything good in the Blackass generation?

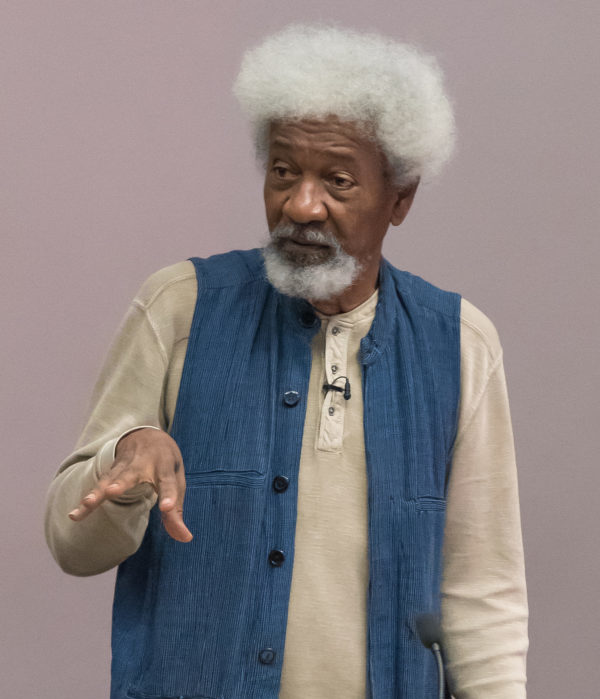

While we can’t speak for that whole generation of writers, we do know what Soyinka thinks. And if anyone’s opinion of our literary moment should matter, it is Soyinka’s. He has been through over half a century of African literary history. He is both an eyewitness to and active participant in the major milestones that catapulted African literary community to global influence. He was there during the optimism and creative abundance of the 1960s, the decline of the ’70s, the drought of the ’80s, and the slow re-emergence of the early 2000s. He is here today and, yes, he is a keen observer of what he calls the “younger generation.”

So what does Soyinka think of contemporary African writers? Soyinka approves. He told this to a room full of Oxford students a few days ago. He said that “the younger generation” had made African literature “robust.”

During the seminar—which was featured on The Guardian—he opened about about his sense of where his generation stood in relation to the present. He admitted that writers from his generation had become “a little bit tired.” “I think our production gets thinner and thinner,” he remarked. They aren’t producing as much as they once did. One could add that they are also becoming less relevant. There is a new generation of readers who still don’t quite know how to relate to Soyinka’s generation and the things they wrote. In a sense, their influence is waning. But Soyinka isn’t worried. Why? Because African literature is in good hands. “It doesn’t worry any of us,” he says, “because the body of literature that is coming out [is] varied and liberated.”

It’s nice to see Soyinka celebrating the diversity and openness that define contemporary African writing. African writers are more open today to trying out new and unconventional things. In 2013, Lauren Beukes, a South African novelist, pens a brilliant novel consisting entirely of American characters. That same year, Adichie writes a novel about hair, and it grips the imagination of the world. The following year, Nnedi Okorafor stuns the world with a story about aliens landing in Lagos while Igoni Barrett scandalizes the world with a Lagosian rewrite of Kafka’s Metamorphosis. The flowering of poetry in the last couple of years has been quite remarkable to observe. Safia Elhillo, Warsan Shire, Gbenga Adesina, and host of young poets are out there reinventing African poetry for the millennial reader.

Soyinka attributes all this to a new sense of creative freedom. Writers today are not troubled by what he calls “ideological spasms.” They are not married to political agendas. They are not interested in shrinking the African world to political frameworks. They are more concerned about pushing the boundaries on storytelling and poetic creation and inspiring us, the readers, to imagine Africa differently. That’s why, referring to our generation, Soyinka said, “this next generation has been freeing itself and the result is really marvelous, very varied—the women in particular.”

Soyinka’s shout out to African women writers is also worth noting. In 2011, Soyinka made a similar comment in a video interview. He said point blank that African women writers of today are outperforming their male counterparts. He is right. We won’t even attempt to make a roll call of this army of women essentially shaping contemporary African literature. The list is literally endless. It’s great that Soyinka acknowledges it. But we still need to do more to celebrate this dominance of women in the African literary landscape.

There you have it. Soyinka’s loves and is impressed by authors we love and read! He could easily have played the part of the sour old man who dismisses the young as clueless. But he didn’t. And that’s something to hold on to.

**********

Post image by Jodie C via Flickr.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions