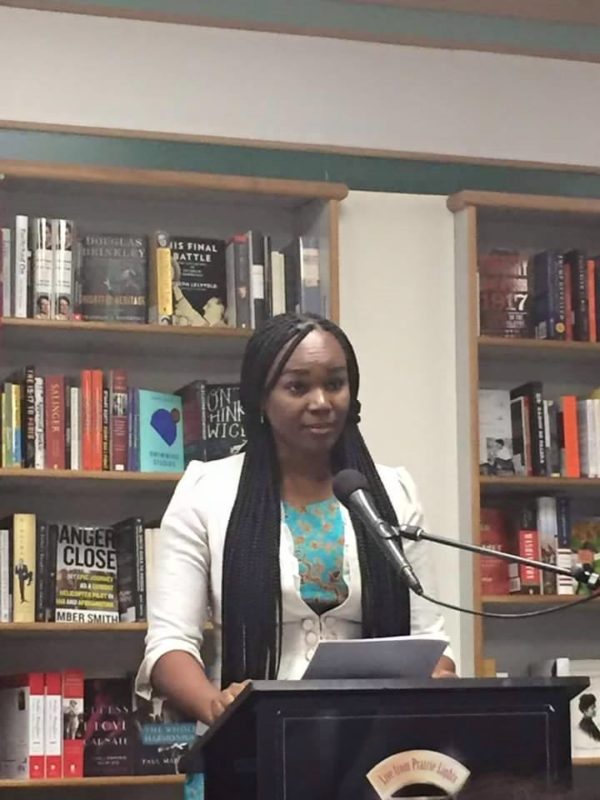

Ukamaka Olisakwe is the author of Eyes of a Goddess, her debut novel published in 2012 by Piraeus Books, Massachusetts. Her stories have appeared in various online journalist and blogs including Saraba, Sentinel Nigeria, Short Story Day Africa, Naija Stories, and featured in many other local and international platforms like the New York Times and the BBC. She was selected, in 2014, as one of Sub-Saharan Africa’s 39 most prominent writers under the age of 40.

In this interview, granted while she was on two writing/residency programs in Iowa and Pittsburgh in the United States, we discuss her work, her outlook, her future plans, and experience living, for a few months, in the United States. She has since returned home. Enjoy

***

How would you describe your 2016 in terms of your writing career?

I think 2016 has been a great year. I had the opportunity of meeting and interacting with writers from 30 different countries. I will always remember this year. It was a kind of rebirth. 2016 shed light on what I should bring more to my stories.

You’ve had quite a busy couple of weeks in the US? Tell me about what brought you here.

I was selected to be part of the University of Iowa International Writers Program. The 10-week Fall Residency gave us space to write, to exchange ideas and also the opportunity to see different cities and what makes each one distinctly different from the other.

So we spent the best part of this period in the university town of Iowa, and then traveled to places like Chicago, New Orleans, Washington and New York.

What is the experience like as a first time visitor?

It is very different from the America I watched on TV; living here, I understood what it means to be black. At home, we judged people mostly by their names which tells their ethnic group, and their religion. And not the color of their skin.

So, my first few weeks in the United States was quite a challenging one. I learned what it means to be a black woman, especially in the midwest. I learned what loneliness feels like. There was also the tremendous cultural differences I struggled to deal with. But things got better and it is thanks to the new friends who have become my family, who showed me one time, like the Igbo say, that Nwanne di na mba. They redeemed America for me.

You were in Iowa, presumably, during the primary and election process. What did you take away, especially compared to the Nigerian system?

I was in New York City on the day of the election and flew to Pittsburgh*, where I currently live, when the results rolled in.

I think the pulse is same back home. Many times, I met people handing out flyers to passersby and holding rallies on the streets. They struggled to convert undecided voters. It was no different from the active campaign championed by women like Fúnkẹ́ Phillips, Petra Akinti Onyegbule and Viola Ifenyinwa Okorie during the 2015 presidential elections.

People invested a lot of emotions into this election and they were devastated when their choice candidate lost. It brought back memories of our own time, how we fought so hard, even on social media. We lost friends. We still hurt, deeply. And it is the same experience many friends in the United States are presently going through.

What stood out in all the places you visited?

I spent most of the first ten weeks in Iowa, then traveled to Chicago, New Orleans, Washington and New York. Now I live in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, where I am concluding a second residency.

I learned a lot about myself here: I am not the big city girl. I crave tranquility. I am at my best when I am away from the noise of big cities.

I found Chicago obscenely beautiful and extensively distracting. There was so much to see, so much noise to deal with; these forces interrupted my creative process. I couldn’t pen a single line all through my stay there. When I returned to Iowa, I refused to leave my room for two days.

New Orleans reminded me so much of my hometown, Abagana. I could live there forever. There is music on the streets, a healthy mix of people from different races. You walk down the streets and you don’t feel like you are alone, and strangers had nice things to say, if they really needed to say it. The sense of community seemed strong in New Orleans, and though it had its share of noise, it was a comfortable one.

I think I loved New Orleans better because some of the southern cuisines are prepared almost like we do back home. The jambalaya rice, a popular delicacy, is a cheap rip-off of our Nigerian jollof rice. LOL. My point is this: we have so much in common. The sense of community is striking—you can almost reach out of your window into your neighbor’s home.

Washington reminded me so much of Abuja. I wanted to see all of the Smithsonian Museums. But I could only see the National Museum of Natural History and the National Museum of the American Indian. Tickets for the new National Museum of African American History and Culture had sold out.

In New York City, I saw everything I had read about, from the Statue of Liberty to Wall Street, the New York Public Library, the Rockefeller Centre, Tiffany’s, Fifth Avenue, the Guggenheim Museum, Central Park — I wanted to see everything. And I did.

But what stays with me now are the contrasting images of wealth and poverty. The haunting images of homeless people on the streets. Mums and toddlers lounged at every corner in the blinding cold. Men and women crouched on sidewalks, holding out plastic cups, begging for quarters. Young men peddling CD plates or performing on the streets, pushed their wares in your face. Acrobats gave their best performances for interested tourists. Tired men and women milled around, pushing ads and flyers of tours busses in your face, so they can get commissions.

And you can’t miss the rich. You find them in the stores, from Tiffany’s to Giorgio Armani, poking through insanely expensive luxury items. They are the tiny population who can afford to live in Manhattan. Others take the Subways from the suburbs to Times Square to struggle for this elusive American dream.

New York City is haunted by crushed dreams.

How would you rate the experience of the writing fellowship overall? How do you think it will affect your writing career going forward?

I think the writing fellowship is the greatest gift any writer can get, especially writers from my community who have no institutional or even, community support. The cultural exchange opened my eyes to the components I should bring more into my story. I was able to reassess home from the outside and interrogate our realities. We have so much stories to tell. But we also need a strong support structure.

I think a community faces the risk of losing its creative people to other countries because they are given the solid ground to express themselves the way they want. We need that to improve on the quality of works we churn out.

I noticed that you still maintain a full-part-time job writing journalism for OlisaTV even during your fellowship. How are you able to maintain that in what I presume is a tasking schedule?

I don’t want to go hungry. Times are too hard and being unhealthily dependent on someone else for survival scares the devil out of me. So, I multitask not because of love. It is enervating.

Your book Eye of a Goddess was called one of the This Is Africa‘s “Best 100 Books 2010-2014, and your short story that got you into the Africa 39 was well received and well reviewed, should we expect a short story or a new novel out soon?

Jalada published my short story ‘Nkem’s Nightmare’ this May. Presently, I am working on a longer work of fiction.

How do you write? Any special rituals?

I write longhand, before transporting the written thoughts to my laptop. It may sound tedious but I have learned I have better clarity of thought when working with a pen and paper. There is something intimate about that process, I think the closest explanation that comes to mind is the excitement from back in the days, when we wrote love letters to our peers on pages torn from our notebooks.

I write anytime I find space — in bed, while walking down the street, at a park. I simply just sit, whip out my pen and the large notebook I lug around, and write. This is mostly triggered by a voice, the lonely couple walking down the street, the laughter of children, or even a newspaper clipping.

As a witness to the election outcome, and as a woman writer, what was your opinion about the election of Mr. Trump?

I think it was very devastating because one woman’s success is the victory of every woman.

We live in a world where girls are not allowed to dream too big. From a tender age, girls are taught to act pretty, to be demure, to shrink themselves for the man. Hillary Clinton running for president was a source of motivation, not because she’s the first woman to run for office, but the media coverage, the daily hammering of the American elections, displayed on televisions from my village in Abagana to Sitka in Alaska, was a historical battle many girls all over the world were aware of.

And I like to think that many of these girls nurse great ambitions. So, watching a woman slug it out with a man like Trump, sends a message about standing strong in the face of misogyny and patriarchy. Hillary Clinton’s winning would have been a push, a necessary encouragement.

But majority of voters in the Electoral College preferred Trump and it was a blow.

What do you look forward to on return to Nigeria after your fellowship?

I want to hug my children and hold them to my chest forever. I also want to show them the success I have made with my writing.

Thank you for your time.

***********

*At the time the interview was conducted, Olisakwe was still living in Pittsburgh.

***********

About the Interviewer:

Kọ́lá Túbọ̀sún’s has done work in African literature, linguistics, teaching, and journalism. He recently appeared in Literary Wonderlands: A Journey Through the Greatest Fictional Worlds Ever Created, an anthology edited by Laura Miller. He is the winner of the Premio Ostana “Special Prize” 2016 (awarded in Ostana, Cuneo, Italy) for his work in indigenous language advocacy. He is on twitter at @kolatubosun.

Kọ́lá Túbọ̀sún’s has done work in African literature, linguistics, teaching, and journalism. He recently appeared in Literary Wonderlands: A Journey Through the Greatest Fictional Worlds Ever Created, an anthology edited by Laura Miller. He is the winner of the Premio Ostana “Special Prize” 2016 (awarded in Ostana, Cuneo, Italy) for his work in indigenous language advocacy. He is on twitter at @kolatubosun.

Hannah January 11, 2017 04:40

Her descriptions of the cities she visited, the insightful observations of people on the streets put me right there with her, carried me along.