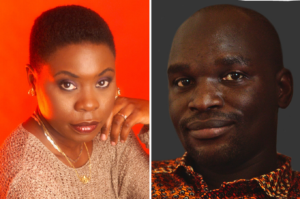

Romeo Oriogun was recently shortlisted for the 2017 Brunel International Poetry Prize. We published his “Metamorphosis” in June of 2016 and his “The Final Portrait of a Dead Artist” in February of this year. Raw, sensuous and disarmingly beautiful, his poetry explores LGBTIQ experiences in a violently homophobic Nigeria.

Over email, we had a question and answer session with him. Here, he discusses the continual outburst of homophobia on both the Internet and in everyday life, the extent to which art is a response, how he writes from a place that embraces what it means to survive in the dark, and what he has learned from Sylvia Plath, Anne sexton, Essex Hemphill and JP Clark.

Read below.

***

1. Congratulations on your shortlisting for the Brunel Poetry Prize. We at Brittle Paper are excited for you.

ORIOGUN: Thanks.

2. Your poetry embodies a tension of beauty, violence, wonder and sensuousness. Boys are physically attacked for loving boys, boys remain enraptured by their discovery of their love for boys. All these come together in a thick ache, like in the final six lines of “How to Survive the Fire.” Homophobia meets the tenderness of this love and love shrinks in manifestation — like in your Brittle Paper poem “The Final Portrait of a Dead Artist” — which doesn’t mean that fear can tame it — a truth wielded so beautifully in these lines from “Burnt Men,” the titular poem from your Praxis chapbook: “sometimes I see fire in the mouths/ of young boys/ and all I want to do/ is kiss them to sleep.” Do you think that beauty or purity would ever be enough?

ORIOGUN: Last year a gay man, Olubunmi, was lynched to death in Ondo. It is important that we name them, those that are dead, those that are beaten until they are silenced. It was a time when homophobia raised its head in posts and tweets on social media. A friend who is gay reached out to me, and all he asked was why. It is a question I’ve been asking myself, why the hatred, why are boys who seek nothing but love condemned to lynchings and death. Even when they are hidden in their rooms, there is still this fear of being discovered. Still there are boys falling in love. There’s a vibrant underground scene. There are places that are safe zones for queer people, but these places shelter people that are privileged. I’m more concerned about queer people from the lower class, queer people living in slums and Face-Me-I-Face-You apartments; I’m more concerned about queer people who can’t buy a safe space in this country, those who have to protect their identities before it becomes a red flag. For those kind of people, beauty or purity is not enough. It does not help them to survive freely because religion and society have taken a permanent room in the heads of most people that it would take a lifetime to unlearn what has been learned, because everyday they must navigate through a society that wants them dead because of their sexuality. There are a lot of atrocities being committed against queer people that goes unreported because they don’t have a voice, because when they talk they are told to keep quiet, to accept their fate because they are illegal. When I write I merely document the battles going on in queer bodies; I do not think my poems are going to make life better for queer people because I feel this battle for freedom may not be won in my lifetime. I merely write to tell the future that we were here, that we fought to be seen, to be looked upon as humans. I write to tell other queer people who look upon their bodies as sin that what they feel is natural and beautiful, that their voices are valid and there are other people like them out there, that they are never alone although there are times when someone emails me to say my poems have made him see queer people in new light; during those times I feel happy because they have found home. Despite all the struggles, the truth is queer people are still living here. We are still falling in love. We are still alive and maybe we are not that free to love, but we try and fear has not and will not conquer us.

3. In a conversation I had with a friend recently, about the different things emotion and technique can offer to art, your “Invisible Man” came up. My friend is convinced that that force in your poetry — the frequency with which haunting emotional punches appear in your lines — comes not only from a place of raw intensity but mainly from your constantly being in that place. My friend believes that you do not “call” it up, that it is always present. What would you say about this?

ORIOGUN: I think there’s a battle going on between queer people and homophobes. It has been hidden but with social media there’s increasing awareness going on about it and we are all caught up in it. I identify as queer and so I’m caught up in this battle and when I write I write from there, maybe that’s why there’s this need to name this pain I feel. Maybe I’m writing from a place that knows what it means to survive in the dark and when one lives during a war you do not call up memories. It is always in you, it haunts you, torments you, and when I write I’m trying to also make sense of what I feel. I’m naming this pain that has always been inside me. I’m saying I was there, these are what I saw, these are my memories, deal with it.

4. Do you have favourite poems or poetry collections and poets? What specific thing have you learned from each?

ORIOGUN: I love Sylvia Plath’s Ariel. It gave me permission to write about memories, to go into my body and write down the battles it has faced without holding anyone sacred. There’s also Essex Hemphill; I don’t own a collection of his as some books are rare in Nigeria but his poems gave me a reason to believe that my voice is valid. I’m Bipolar and until I met Anne Sexton’s poems I thought I was alone. JP Clark’s “Streamside Exchange” told me boy life will fuck you because it is not stable and you must deal with it, you must write it down, you must live with it until you triumph. I think Sylvia Plath, Anne sexton, Essex Hemphill and JP Clark have more influence over my poetry than any other poet I’ve come across. There are a lot of fabulous poets out there and from each one I learn how poetry can evolve, how it can be used to speak about memories, to map sadness and joy, to see the body as a road that must be traveled upon and how every journey is valid.

5. What are you currently reading?

ORIOGUN: I’m reading Richard Siken’s Crush, Ordinary Heaven by Ladan Osman, Loop of Jade by Sarah Lowe, Mandible by TJ Dema, and A Thousand Splendid Suns by Khaled Housseini.

*****

Read more of Romeo Oriogun’s poetry on the Brunel Prize Website.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions