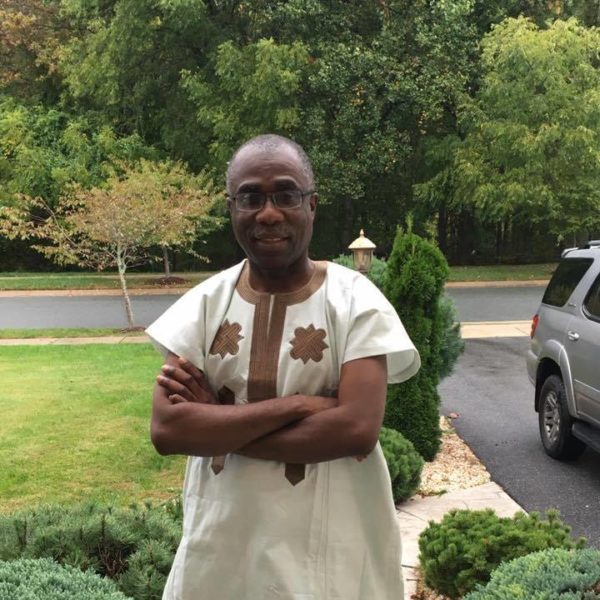

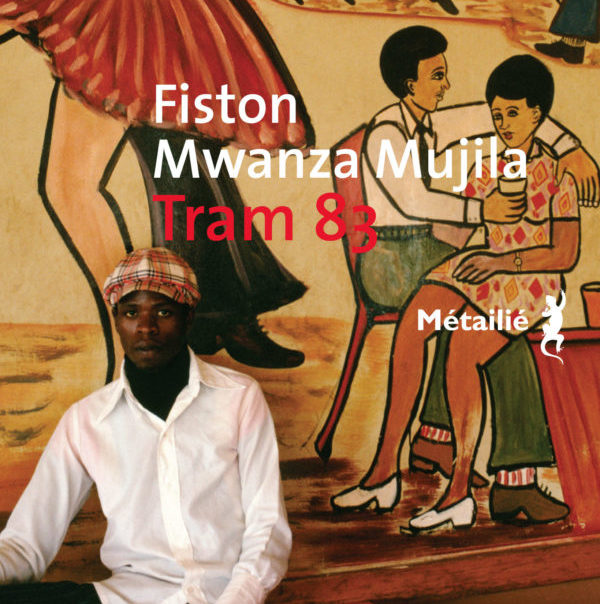

Two days ago, we covered an important conversation that had started on Facebook in reaction to Ikhide Ikheloa’s essay in which he described Fiston Mwanza Mujila’s 2015 Etisalat Prize-winning debut novel Tram 83 as misogynist and poverty porn. It was a truly continental conversation that drew in a host of thinkers: South Africa’s feminist novelist Zukiswa Wanner who didn’t like Ikhide’s portrayal of the 2015 Etisalat Prize judging panel; Kenya’s Jalada Africa co-founder Richard Oduku who faulted the essay’s anthropological reading; Tram 83‘s translator Roland Glasser who is English and who raised crucial points on book translation; Caine Prize director Lizzy Attree; Ugandan writer-filmmaker-activist Dilman Dila who criticized Ikhide’s perspective; John Hopkins assistant professor Jeanne Marie-Jackson who pointed out the complexities of publishing; Zimbabwe’s Tsitsi Dangarembga who placed focus on the manner rather than the subject of writing; and Ugandan Writivism founder Bwesigye Bwa Mwesigire who was unwilling to absolve the book of misogyny without an extended rereading of its portrayal of women.

The conversation continues.

Yesterday, two of Zimbabwe’s leading writers, Petina Gappah and Tsitsi Dangarembga, made revealing comments on men writing about women’s sexuality. On a post about the ongoing conversation made by Brittle Paper editor Ainehi Edoro, Petina gifted us this:

Really interesting debate. But I think Bwesigye Bwa Mwesigire is on to something that Zukiswa Wanner, who understandably loves the novel, and is keen to defend her choice as Etisalat judge may have missed. (Hi Zooks!) She is absolutely correct that Tram 83 is a brilliant novel in many ways, particularly stylistically and linguistically, and that it is realistic in its depiction of real life. But Bwesigye is correct to highlight the novel’s misogyny. It is possible to write realistically about a particular milieu without you, as author, taking on the realistic attributes of the realism you portray. Adichie for instance wrote about the ugliness of war. But she had enough skill as an author to distance herself, the storyteller, from the reality she was depicting, which is why Half of A Yellow Sun is a novel about war that is clearsighted about its own morality. I would compare Fiston’s book with the work of an equally brilliant but also problematic writer, Marechera, who was unable to see clearly the reality of his milieu including the misogyny underpinning his society’s attitudes to women. In Marechera’s case, it was made worse by the fact that the author’s misogyny was directed particularly against black women, just as in the real life society he wrote about. On a lighter note, I have to confess my own bias here: it takes a lot for me to read books by male authors that feature prostitutes. Every time a prostitute appears, my eyes roll to the ceiling! Maybe it’s a case of them writing what they know, but gee wheez, boys, there are other women to write about

How about featuring churchwomen from time to time? What, not so sexy?? The most recent exception for me though was Mabankou in Black Moses. Maybe Mabankou is just a more experienced writer but I can separate his prostitutes from his view of women. Maybe it helps that he writes quite affectionately of all his characters, even the flawed ones, whereas I found Fiston’s women to be disposable bodies in an otherwise BRILLIANT novel. And this is a GREAT DEBATE!!!

Just to add: at no point in reading Lolita, a novel about a pretty self-deluded paedophile, do you get the sense that Nabokov is into peadophilia. His monstrous character Humbert Humbert is presented with brilliant distancing by the author ,and in the first person too. Then again, Nabokov was a genius. Fiston is on his way!

And in the comments section of our first feature on this, Tsitsi Danganrembga stated:

Yes. I think that depicting misogyny in a way that does not clearly indicate that it is unacceptable means that the mind depicting that misogyny is itself infused with many misogynist tendencies. The way in which any situation or event is depicted is influenced by the position of the narrator and thus is a clear message in itself concerning the narrator’s position. A narrator might have the intention of representing African women in a particular manner, only to be foiled by her or his own perhaps hardly acknowledged biases. I have not read the book in question, but I find this a disturbing trend in a significant amount of narrative by African men, whether literary or moving images. What they appear not to realise or not to be concerned about is that they are reinforcing a negative stereotype of themselves with such narrative. In this way, once again, we do to ourselves what we say we do not want others to do to us. I would wish all of us the courage and wisdom to delve deeper. At the end of the day, though, we can write what we like, whether we are novelists, critics or readers.

On Ainehi Edoro’s Facebook thread, meanwhile, the conversation had expanded to men’s portrayal of women within a text’s all-encompassing world. In response to a comment, Petina stated:

I think it is pretty interesting already in that both sides are right: I have sought merely to provide the link between them, namely that even in depicting realism, an author’s moral vision and ways of seeing the world can stand out. No one reading Oliver Twist can misunderstand the “function” if you like, of Nancy’s prostitution within Dickens’ larger moral vision. Damn, I think I am ready to do a PhD on male writers and prostitites!

Using Achebe’s writing as an example, Ainehi pointed out an author’s power to shape perception even when working in a realist tradition that demands a factual base:

I’d say the same of Achebe, who has also been defended on the same terms. Achebe’s women are all so accessory to his imagined African past. He completely forecloses the possibility of seeing the world through their eyes. They are all either dying, or being beaten, or goddesses, or else they are simply cooking in the kitchen, popping out babies or commenting on how Okonkwo is the best things since sliced bread—these stock roles excludes them from giving access to their world in any meaningful way. Achebe’s women are little more than narrative props. And apologists have tried to tout the line “oh, he is simply portraying the realism of an African past which was essentially a man’s world.” But I say realism cannot be used to account for an author’s blinkers.

Ikhide Ikheloa came in and highlighted the lack of aesthetic distance between the novel and its author, but particularly the absence of this acknowledgement in the novel’s reception until now.

…for daring to say that the book Tram 83 reeks of misogyny. It is interesting that no one, no one, ever brought it up in public. I mean, there was no attempt at “distancing”; none, zero, zippo, women are disposable condoms to be used at will. And I am supposed to just sit down and shut up because that is what you do when authorities have blessed the latest literary sliced bread from “Black Africa.” In the 21st century.

Una try!

I know, Bwesigye agreed, I am talking really about the reviews, the blurb writers, etc. etc. And it is not lost on me that Bwesigye hinted that there were “whispers” of misogyny. Nobody wants to be mauled.

Lizzy Attree dropped by.

Tram 83 just rose to the top of my ‘To Read’ pile. I recall Tendai Huchu loving it and recommending it to me in Bagamoyo recently – can I drag another writer in to this debate? For me, with only one novel to go on, comparisons with Achebe can wait

Ainehi Edoro acknowledged the equal validity of the several considerations and readings:

Then again, I don’t want to go on some blindly vicious moral crusade against a novel while completely drowning out the question of formal and aesthetic innovation. It would be a shame to portray Tram 83 as some kind of failed novel that nobody should care about because it misrepresents women. Seems a bit too simplistic to me.

Novels are complex eco-systems of form and ideology. Let’s not forget that.

In response to Petina’s statement about critiques being read as malice, Ikhide further made comments about his own perceived malice:

The charge of malice, etc. is not new in my case, I have heard it said many times that I am a hater that seeks to bring down others. I try not to take it personally, these are difficult conversations and the initial reactions often are to be defensive and dismissive. I expected that. People have put in a lot of awesome work on behalf of literature and so when you question assumptions that drive their work they are bound to be unhappy.

The charge of malice is inappropriate. I do not compete for literary prizes and resources with anyone and I dare say I have been a relentless cheerleader, mostly for free, for the work of our writers. Look at my recent essays on the works of Elnathan John, Abubakar Adam Ibrahim, Sarah Manyika, Okey Ndibe, etc. and come to your own independent conclusion about whether I am a hater of your works or a lover of “happy stories.”

Anyway, let the conversations continue, I thank Otosirieze Obi-Young for a brilliant essay that cut through the emotions and forced a respectable conversation. I actually thought of submitting the essay to Brittle Paper but at the last minute decided to just dump it on my blog. In a sense, I am glad I did. The indignities I own. Ainehi Edoro, you are absolutely right, Tram 83 is important on many levels, some of them for the reasons that got me in trouble with establishment writers. I love reading, I also love writing, I am not going away.

Ikhide, meanwhile, had published on his blog another essay, a reaction to the reaction to his first essay. Here is an excerpt.

1. My essay isn’t so much about Tram 83, but about the politics and power of narrative and how we conduct business. It’s an old debate!

Sounds harsh, but after reading Tram 83, I wonder if the narrative that passes for “African literature” in the West helps or hurts “Africa.”

2. Many African writers of stature have attained fame and decent living from attaching themselves to the title “African writer.” Prizes, grants, fellowships, conferences are devoted to “African writing” and these things are heavily subscribed to by the same African writers who now chafe at the term. You can’t have it both ways. If you have allowed yourself to be defined (and limited) by a term, the reader should be forgiven for looking at you through that lens. You can’t be posing as a Western-sponsored African writer, and when asked questions you drop the tag, “African.”

….

6. What gets lost in translation is important. The unintended consequence might come across as utter disrespect. Remember, the act of telling our stories in English, and then on paper, is in itself two levels of translation. We are built in the oral tradition. Moving from French to English is this at least three layers of translation. A lot gets lost in translation. When the narrator in Tram 83 seems to mock a people whose cuisine is “dog cutlets and grilled rat” it is impossible to see them as human beings worth engaging in on a respectful level. It is your language, you already have power over the narrative, if I told you that your foie gras is obtained from doing savage things to the liver of a cute bird (the lovely goose) I am communicating to you that I don’t take you seriously. You are savages. Where I come from we don’t eat sautéed termites, we eat irikhun. If you do not understand why this is so offensive to the reader, then we are on different planets.

7. Again, the translation in Tram 83 did nothing for me, with all due respect. I read Chinua Achebe’s Things Fall Apart in English, it was as if I was speaking Igbo, I read Camara Laye’s African Child in English and it was as if he was reading to me in his language. Do the people really eat “grilled rat”? Is that what they see on their plates?

Richard Oduku himself expanded his brainy Facebook posts in defence of Tram 83 into a solid essay titled “Poverty Porn: A New Prison for African Writers.” Pointing out the deficiencies of anthropological reading in an era of genre-bending literature, he cautioned against analysing works based on a “particular contemporary political view.” Here is an excerpt:

We seem to have this long list of instructions that a novel by an African should abide by. A few years ago, Helon Habila made an unlikely charge at ‘We Need New Names’ by NoViolet Bulawayo, that it was pushing an aesthetic of suffering – poverty porn. I couldn’t stop shaking my head. That was shocking. I read Pa’s review and I could not stop seeing the listing of what should be done, should not have been done … Pa also brings the poverty porn argument to Tram 83.

Most of the complaints about descriptions of place and people, reminds me of the “decadent” allegation heaped on Dambudzzo’s work. Poverty porn is our new prison, a lexicon borrowed from development critics. But this phrase even becomes more problematic when it is applied to a creative work, say a novel, because it automatically presumes that the work was written that way primarily to increase sales, for African novels, in a Western market, and there is a deliberate kowtowing to certain demands from the Western publishing system (editors, publishers, readers). It has become a

simple way of shooting a novel down, of refusing to engage with its unpleasant contents.

I suspect that so many of such cases are happening. It would be sad if another Marechera is being washed down the drainage as we speak. Works are going to emerge that are so different from certain cemented talking points by African critics and they’ll all be labelled as not contributing to “continental building”, as not adding shine to the ‘sunny’ Africa we need to present to the West, and they’ll be demonised, when the problem maybe that critics have adopted narrow lenses.

***

Read our first coverage of the conversation.

Read Ikhide Ikheloa’s essay, “Mujila Fiston Mwanza’s Tram 83: Requiem for the African Writer, and again, the Balance of Today’s Stories.”

Read Richard Oduku’s reaction essay, “Poverty Porn: A New Prison for African Writers.”

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions