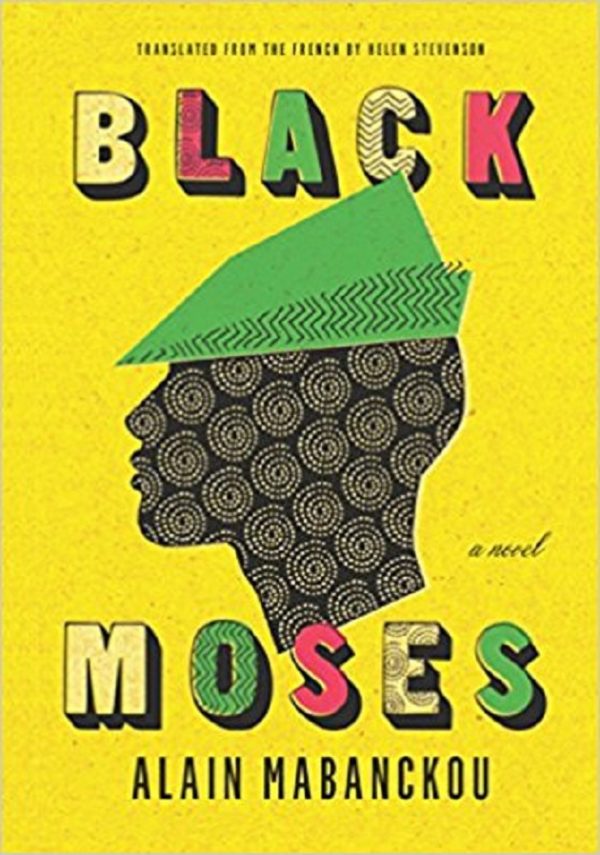

Alain Mabanckou’s eleventh novel, Black Moses, was longlisted for the 2017 Man Booker International Prize. It was translated from French by Helen Stevenson. Described by The Guardian as “Oliver Twist in 1970s Africa,” the book was published in the UK by Serpent’s Tail and in the US by The New Press.

Straddling both Francophone and Anglophone writing, Mabanckou is, quite simply, one of the continent’s greatest living writers. He has been described as “Africa’s Samuel Beckett.” Earlier this month, we published an in-depth essay on his remarkable body of work. A professor of literature at the University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), he will headline the 2017 Africa Writes Festival.

Read the excerpt from Black Moses, as published in Literary Hub, below.

*

In fact, until the year the Revolution fell on us like a rainfall which even the most celebrated fetishers hadn’t seen coming, I believed the orphanage at Loango was not an institution for minors who were parentless, or had been mistreated, or who had been born into a problem family, but rather a school for the very gifted. Bonaventure was more realistic, he said it was a place where they kept all the kids no one wanted, because if you love someone, if you want them, you take them out, go for walks with them, you don’t shut them up in some old building, as if they were in captivity. He based this on his own experience, and on his own inability to understand how a mother such as his own, who was still alive, could leave him there, surrounded by all these other boys and girls, each with their own ‘serious problem’, which led inevitably to their admission to Loango.

In my mind, our studies at Loango were designed to make us superior to most other children in the Congo. This was the impression we got from Dieudonné Ngoulmoumako. He liked to boast that he was Director of one of those public establishments whose academic results were equal in every way to those of the state primaries, secondaries and lycées. He’d puff out his chest and declare proudly that the masters and teachers at Loango earned more than their colleagues at the Charles-Miningou primary, Roger-Kimangou secondary and even the Pauline-Kengué lycée, the most prestigious lycée in Pointe-Noire. He was careful not to admit that if these teachers were indeed better paid, it was no thanks to the charity of the President of the Republic. The running costs of the orphanage and the salaries of the staff were provided for by the descendants of the former kingdom of Loango, who wanted to show that their monarchy continued to exist, at least symbolically, through the generosity of its heirs. However, as I perceived it, our orphanage was separate from the rest of the Congo, in fact from the whole of the rest of the world. Since the school was in the hinterland, we knew nothing of the neighbouring agglomerations of Mabindou, Poumba, Loubou, Tchiyèndi, or our own economic capital, Pointe-Noire, which was spoken of as though it was the promised land Papa Moupelo used to talk to us about.

Yet the village of Loango was only about twenty kilometres from Pointe-Noire, and according to Monsieur Doukou Daka, our history teacher, it had once been the capital of the kingdom of Loango, founded in the 15th century by the ancestors of the vili people and other southerners. It was here that their descendants had been taken into slavery. Monsieur Doukou Daka raged against the whites who had taken our strongest men, our most beautiful women, and piled them up in the ship’s hold to make that dreadful voyage to the land of the Americas, where they were branded with irons, some had their legs amputated, some were left with only one arm, because they’d tried to run away, even though it would have been impossible to find the path back to their village.

Monsieur Doukou Daka would turn his back, lower his voice, and look out of the window, as though worried he might be overheard, then confide in us, in aggrieved tones, that many of the rich business people in Loango had been involved in the trafficking and had sent their sons to a region of France called Brittany to study the secrets of the trade.

‘You see,’ he’d murmur. ‘Sometimes we were sold by our own people, and if ever, one day, you meet a black American, remember, he could be a member of your family!’He seemed to bear a grudge against the vili, particularly since he himself was a Yombé, an ethnic group despised by the vili, who considered it a tribe of barbarians from the Mayombe forest. The vili and the Yombés, even though they were in the majority in the Kouilou region, each held the other responsible for the misfortunes of our ancestors.

We were shocked when, with his arms pressed to his sides, as though to emphasise his disappointment, Monsieur Doukou Daka shouted:

‘What’s more, the vili took the people of my own ethnic group into slavery and sold them to neighbouring kingdoms! So don’t come telling me that it was the white men who taught them about the bonds of slavery! White men still hadn’t arrived at that point. End of story!’

Read on HERE.

The Impossibly Dapper Novelist: A Look at Alain Mabanckou’s Style File | Africa Writes June 22, 2017 06:43

[…] followed and established him as the storyteller of the unconventional. He is brazenly committed to experimentation at the level form and language. There are artists who find success by nurturing a worshipful relationship to tradition. That is […]