Mr. Tádé Ìpàdéọlá is a barrister at law, writer, and poet. His latest poetry volume, The Sahara Testaments, won the 2013 Nigeria Prize for Literature sponsored by the NLNG. It was the last time, until last week Monday, that the poetry prize was awarded. In 2009, he won the Delphic Laurel in Poetry for his Yoruba poem “Songbird” at the Delphic Games in Jeju, South Korea.

It is his role as a judge in this year’s Nigeria Prize that fascinated me, especially because of the amount of controversy and positive vibes it generated. On the one hand, he is a former winner and contemporary writer whose presence on the judging panel brings an invaluable diversity. On the other hand, he is a writer and publisher with a number of his friends, colleagues, and mentees in the running. I wanted to know how much this weighed on him, along with other matters relating to this year’s award, won by Ikeogu Oke.

Enjoy.

Interviewer

What is it like to be in the other side of the table at the NLNG, from writer/prizewinner to judge?

Ìpàdéọlá

It felt a little onerous. The demands of the other side of the table as you put it are of a different kind and degree. As a competitor, I probably have other competitors in the peripheral vision but as a judge one sees all of them and their different strategies. For me personally, it was a vantage point from which to view the development of our poetic output over the past four years. I remember thinking that I wouldn’t like to get in the ring with many of these extremely skilled poets. There was a lot of kitsch but there was emphatic, undeniable talent in the top 20% of the entries ranging from old masters to new writers.

Interviewer

Where is the better place to be?

Ìpàdéọlá

That depends on what you are measuring but the more comfortable place for me is at the scriptorium.

Interviewer

Are there any insights into the judging process that you think is worth sharing here, especially for writers who will be entering next year?

Ìpàdéọlá

Definitely. Young writers should learn to engage proper editors. Don’t call a single volume of poetry that you wrote an ‘anthology’, for example. Don’t put weak poems in front – or at the rear. Try to become familiar with what the generation before you did and try to improve the practice of your preoccupation.

Interviewer

Why wasn’t there a prize for literary criticism again this year? For some reason, I don’t buy the argument that there are no good critics or worthy entries, and I say this not just because I was an entrant this year. What exactly is the problem?

Ìpàdéọlá

That category of the Nigeria Prize clearly needs tweaking. We know the Wright brothers weren’t ‘professional’ aviators. There were none before them. They invented aviation as we know it today, as amateurs. But that is if one employs that word with its roots in mind. They were in love with flying. T.S Eliot famously said there is no method to criticism except being intelligent. I think intelligent criticism of our literature should be welcome at all times and it shouldn’t matter if there are only two such entries in a given year. The American Academy of Science had a great deal of engineers but those were not the people who gave wings to mankind. We should respect common folk who speak with common sense.

Interviewer

One of the reasons why many people were initially happy that you were selected to be in the judging panel is the idea that having a young person (and one with deep roots in contemporary styles and traditions) will be able to drag the professors into modern times, so to speak. First, did you feel the sense of that duty, and secondly, have you carried it into the work, using this year as an example.

Ìpàdéọlá

I doubt that a man close to fifty is young. Life expectancy in Nigeria is so short I should be out of the picture by now. But seriously speaking, the judging process of the prize has come a long way. There was a time people didn’t know who the judges were.

The issue isn’t the age of judges, it is competence. If, knowing what I now know of the matrix for judging entries some further improvements can be made, all for the better. I can’t possibly go into details but the process right now is scientific to a large degree and is designed to throw up a winning entry through consensus. That can be great when the choice is great and terrible when the choice is terrible. The quality of mind of judges matter. Old age teaches you how to think about what you know. Youth, for the most part supplies energy. Speaking generally, it is like playing chess with your computer now. If you go by logic alone you lose. The place of intuition is the place to make a leap. We need a matrix that can not only play chess but one which can play Go as well.

Interviewer

I have spoken with many people who think there is something of an acada-influenced snobbery at the NLNG? Do you know why people might get that idea? And do you share it?

Ìpàdéọlá

Well, popular culture isn’t always literature and literature isn’t always popular culture. If the aim is to throw up the best in thought and culture, on rare occasions you find it on the streets but most times you find it in spaces dedicated to the nurture of mind. It is actually interesting that you asked this question because on Monday I had a brief chat about this element in particular with Dr Kudo Eresia-Eke of the NLNG and I remember referencing the life and recent death of Vladimir Voevodsky who was such a mathematical genius that though he was repeatedly kicked out of different schools, true mathematicians from the top schools around the world always found ways of getting him to work with them. How many mathematical prodigies does the world have? Thousands. But of those, only one has dared to reinterpret the equal sign. And the challenge is to have academics who can spot that one talent among a thousand talents. Oxford found Ramanujan. Who and who have our academics discovered? That is the real challenge. It is almost unreal, for example, that Adebayo Faleti and Olatubosun Oladapo don’t have a hundred or more honorary Doctor of Letters awards between them. You have to hold academia which remains wilfully blind to such staggering talent in contempt.

Interviewer

What’s your opinion on the idea that joint winners are bad for the prize?

Ìpàdéọlá

Now you are carving close to the bone. Obviously, literary prizes aim for singularities. I just cited Olatubosun Oladapo and Adebayo Faleti. Perhaps in that entire generation, only Olanrewaju Adepoju compares. So you have a thriving culture of over forty million people and you want to award these giants joint awards? These are rare, extremely rare talents and ought to be recognized as such. But there are exceptions and there are precedents in the Nigeria Prize itself. The challenge is to know when to make such an award and when to go for the singularities.

Interviewer

Is the claimed unanimity of voice every year by the chairman of the judging panel an important factor in the value of the prize? Or do we need to add dissenting opinions like they do at the Supreme Court? As a lawyer, I’d hope you’d be open to that idea, not as a way to cause controversy but as a way of generating new conversations every year post-prize.

Ìpàdéọlá

In the natural progression of things, the dissenting or minority opinion will become a part of our culture. It is perhaps interesting that one strength of the winning entry this year is that argument for not killing the dissenting voice however unpopular. As you know, my practice as a lawyer advocates freedom of expression. Reason, not primordiality or sentiments should be our organizing principle in society. A society that stifles debate will atrophy. See what became of America the moment its electoral machine yielded to something apart from reason?

Interviewer

I have heard rumors that your presence on the judging panel doomed Peter Akinlabi and Niran Okewole’s entries this year? Professor Ben Elugbe on the Advisory Board denied this, but I wanted to know if you’re familiar with the controversy and if you thought there was anything you did to contribute to it, or anything you could have done to prevent it.

Ìpàdéọlá

*Laughs* Oh, I heard the rumor too. But if you know those poets or their works then you know they don’t need any prize for their works to be validated. Both are prizewinning poets within and outside the country but that is not what makes their works endure. I remember distinctly when PEN International wanted to do a lifetime tribute to the Chinese writer and Nobel laureate Liu Xiaobo using the works of just five poets from around the world, Okewole’s work was the only choice from Africa. The history of literature and poetry particularly suggests that you are more likely to sink into oblivion if you are the feted and lionized poet in your lifetime. The poets you named are poets that past winners of the Nigeria Prize for literature quote. I can illustrate that point with an anecdote from the life of Joyce and Faulkner. Faulkner was the Nobel Laureate but he had the decency and humility not to enter the same restaurant at which Joyce was dining. The legend has it that Faulkner stood outside the window to watch as Joyce chewed his dinner and whispered to a companion standing beside him ‘that is THE writer.’ I’m just one judge and I did quote from Okewole and referenced Akinlabi in The Sahara Testaments. In reality, if I’m Faulkner, those two are the Joyce twins of our literature. I discovered that the idle Nigerian youth had a huge capacity for rumour generation and consumption but would have preferred these ones to write some fiction.

Interviewer

I assume you’re familiar with my essay on context published earlier in the year. How important, do you think, is context in coming to an acceptable winner? And from your inside perspective — to the extent that you can speak to it — how harmful is it?

Ìpàdéọlá

Again, you carve closest now to the bone. What I like is the attention that your essay draws to these issues. The pioneer will start the discourse and it may be heresy at first but as Galileo is reported to have maintained, ‘it moves’.

Interviewer

Is the Prize improving creative output of Nigerian writers today, judging by the entries received this year?

Ìpàdéọlá

I think the top 10% of our writing today will compare favourably with what is coming out anywhere in the world but I’m afraid the 90% is probably average or even mediocre.

Interviewer

Do you still write? What are you working on? What do you think of this myth of this particular prize as a sedative, zapping one’s creative energy for a few years at least (which — as it is said — is why winners haven’t put out any major works after their win)?

Ìpàdéọlá

Of course I’m writing. On twitter. It takes me about 8 years to do a book to my satisfaction and I’m working on two books at the moment. Again I’ve been working with my translators into Dutch, French and Spanish and that takes a lot of time. I’m headed to Brussels and Antwerp to meet my Dutch translators shortly. It takes time. I wonder how Wole Soyinka does it! But seriously now, how many books did Harper Lee write? Books are like wives, it is better to live alone than to marry ill. I’m not under pressure of time and that is a liberating factor, actually. The Nigeria Prize enables you to travel and to enter other cultures at a level which challenges you to improve yours. I have read books in the last four years I wouldn’t have had time to read without some financial buffer and perhaps I suffer from an anxiety not to write below a certain threshold. No day passes I don’t read or write and perhaps like Harper Lee I can wait fifty years for my next book to come out of the press.

Interviewer

Thanks for your time.

Ìpàdéọlá

It was a pleasure.

***********

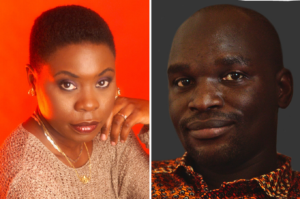

Post image via Peony Moon.

***********

About the Author:

Kọ́lá Túbọ̀sún’s work has appeared in Aké Review, Brittle Paper, International Literary Quarterly, Maple Tree Literary Supplement, and recently in Literary Wonderlands, an anthology edited by Laura Miller. He is the winner of the Premio Ostana “Special Prize” 2016 (awarded in Ostana, Cuneo, Italy) for his work in indigenous language advocacy.

Kọ́lá Túbọ̀sún’s work has appeared in Aké Review, Brittle Paper, International Literary Quarterly, Maple Tree Literary Supplement, and recently in Literary Wonderlands, an anthology edited by Laura Miller. He is the winner of the Premio Ostana “Special Prize” 2016 (awarded in Ostana, Cuneo, Italy) for his work in indigenous language advocacy.

I Sound like Okigbo and Soyinka in a Centrifuge - Tade Ipadeola April 12, 2019 03:02

[…] Ipadeola: In some ironic way, Lasisi Elenu, particularly, has critiqued the popular reception of new Nigerian poetry better than most professional critics. He is the amateur we need. He does what he does for the love […]