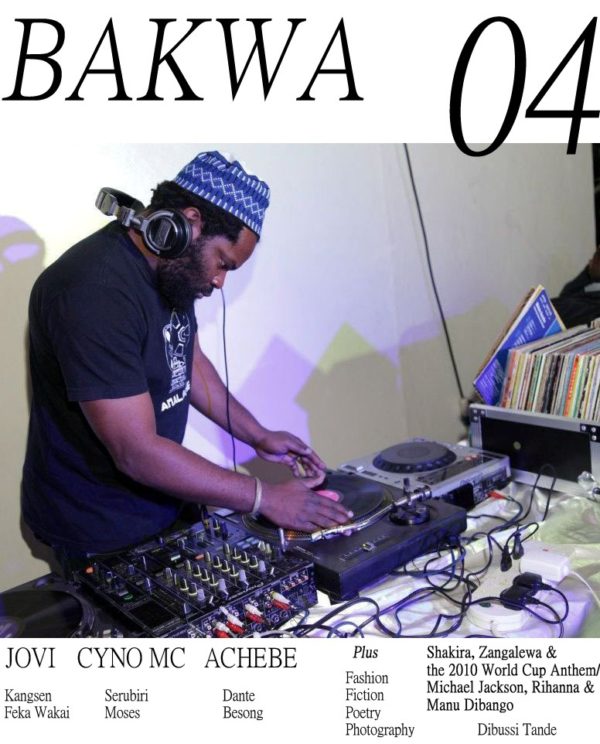

The story of Bakwa magazine—Cameroon’s leading Anglophone literary publication, which also runs pieces on politics and art—is one of sublime dedication and a powerful grasp of responsibility. In 2011, its founding editor Dzekashu MacViban was left unhappy when PalaPala, the Cameroon-based pan-African journal of culture, politics and art, announced that it was closing down. Understanding the lacuna created, his response was to put in place a worthy successor.

In 2014, we ran a review of the magazine’s first six issues, in which the Mexican writer Georgina Mexía-Amador offers this glowing observation:

Bakwa Magazine has put up resistance against silence, misrepresentation and regionalism through a wide array of artistic expressions, such as literature, photography, music, political cartoon and non-fictional reportage. Bakwa is not only concerned with redefining Cameroonian literature and cinema from a perspective that questions the narrowness of a nationalistic agenda, but also with acknowledging the influences that currently shapes Cameroon and the countries and cultures around it; call it, then, a clever expression of Pan-Africanism that has even transcended its immediate boundaries into Europe and America. In a sustained attempt of following the traces of the African diaspora, Bakwa has situated itself in a cross-continental coordinate.

Among the magazine’s recent initiatives have been the Bakwa Short Story Competition and the partnership with Nigeria’s Saraba magazine which led to a literary exchange programme. Last year, the magazine published a new short story by Imbolo Mbue. In a new essay ahead of its 8th issue, MacViban details his journey to fashioning the publication whose existence we are grateful for.

Here is an excerpt.

*

On Tuesday, February 1, 2011, I stared in disbelief at a computer screen in a cybercafé, at a sentence which announced the end of PalaPala Magazine. It was a short, languid sentence, which marked the end of an era. “This is our final issue.” It read, immediately after a thank you note to readers and contributors. “This can’t be true,” a comment followed, to which Kangsen, the Founding Editor replied, “You are PalaPala. Hence, it lives.”

PalaPala was a pan-African journal of culture, and the politics of art and media, which I discovered shortly after the publication of its maiden issue, by prowling the recesses of Chimurenga Magazine online in 2008. I quickly got carried away by other things, and rediscovered it via a mention on Scribbles from the Den, within the same week, and spent the rest of that week consuming it. Founded by US based Cameroonian writer Kangsen Feka Wakai, with the help of Nigerian born artist Abidemi Olowonira and US based Cameroon writer Dibussi Tande, PalaPala quickly became the most important platform for Cameroonian writing and analysis. It was the zeitgeist.

In retrospect, some of the most important conversations on Cameroonian literature (in English) in the 2000s were birthed in issues of PalaPala, notably, Dibussi Tande’s response to Patrice Nganang’s piece “Literature Apartheid in Cameroon,” as well as Wirndzerem G. Barfee’s piece “The Growing Lacuna in Cameroon Anglophone Literary Criticism and Debate.” Wirndzerem’s piece was a critique of the aloofness and critical indifference towards literary production, while nostalgically applauding the 80s, characterized by literary and critical feuds which played out in newspapers and magazines.

In a piece for NABJ Digital Blog, Kangsen described PalaPala as “the kind of forum where Nigerian writer Tolu Ogunlesi can introduce readers to the inimitable Zimbabwean writer Dambuzo Marechera; where Berlin based Kenyan Poet JKS Makokha can evoke his sublime lyricism; where Cameroonian writer Wirdzerem G. Barfee can critique the state of English-speaking Cameroon literature; where Palestinian cultural activist Hadeel Assali can have conversation about poet Mahmoud Darwish and the Houston Palestinian Film Festival, which she helped found.” Despite this description’s aptness, it hardly captures PalaPala’s soulful-cum-tech savvy dimension the way the site’s poetry and podcasts did.

With contributors and readers from cities such as Bamenda, Houston, and Port-au-Prince, PalaPala’s pan African outlook and readership was clear and evident in its issues, such as Houston: Sweet Sweet Bayou (PalaPala #1), East of Bakassi (PalaPala #2), Tori Long, Time Short(PalaPala #8), and For Haiti (PalaPala #9), which provided visibility for many unknown writers and created a community.

PalaPala’s emergence at a time when there was a shrinking of space in newspapers for literary (and cultural) criticism, resonated with the urgency to move the centre of critical analysis from the “tyrannical walls of the academia” to the streets.

As I stared at a computer screen, on February 1, 2011, at what announced the end of PalaPala, I knew I had to do something, but I had no idea what. This feeling was later drowned by the pressure of post-graduate coursework, but gradually resurfaced in the form of nostalgia when I started heavily consuming The New Yorker, Chimurenga, Kwani?, Granta ,and Saraba. By that time, Kangsen was a friend— and mentor— and probably the second most influential literary presence in my life, after my father, Johnnie MacViban.

After I’d read the farewell note on PalaPala, I emailed Kangsen and asked why PalaPala had ended, to which he replied, “PalaPala has done exactly what it was meant to do, and it is better to leave on a high note.” Throughout most of 2011, I communicated almost daily via email with Kangsen, and we spoke about everything, from poetry to politics, as well as the concept and direction of Bakwa Magazine.

Ten months, one day, and six hours after the end of PalaPala, I started Bakwa, in November, 2011.

Continue reading the essay in Bakwa Magazine.

Hildegard January 24, 2018 21:28

Test a new platform of binary options with the tools of technical analysis a set of ready-made strategies. The unique option of «risk-free trade». $ 152 730 Paid to our traders yesterday. Register now and get 10.000 virtual FUNDS in case of right forecast! This is FREE! подробнее тут awlew.tk