Bissau-Guinean writer Yovanka Paquete has penned an essay about the lack of visibility for Lusophone writers, both in Africa and on the global scene, in contrast to their better-known Anglophone and Francophone counterparts. Titled “The Case for Lusophone African Literature,” it is published in OZY. Paquete writes about the promise of elevation that still hasn’t come for Portuguese-speaking writers, inviting agents and publishers to pay attention to the work ongoing in the space.

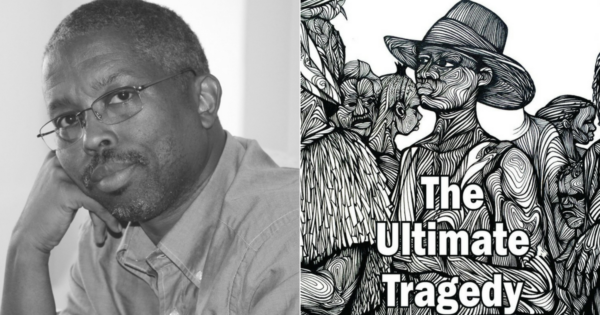

Last year, we announced the Angolan Jose Eduardo Agualusa’s win of the 2017 International Dublin Literary Award for his novel A General Theory of Oblivion, which made him the second African and the first Lusophone writer to achieve the feat. More crucial, however, is the publicity we pushed for Abdulai Silá’s The Ultimate Tragedy (first published in 1995, translated in 2017 and published by Dedalus Books), the first book from Guinea-Bissau to be translated into English, ahead of its launch at the 2017 Africa Writes Festival. We then published an essay by its translator Jethro Soutar on how he pulled it off. Paquete’s essay advances the conversation on Lusophone Arican literature.

Here is an excerpt.

*

A few years ago, I was at an African literature festival that was being held, ironically, in London. Important debates and discussions were buzzing around me. African literature was not yet “mainstream,” but that year, “translations” and “languages” had again become buzzwords. There was a renewed interest in exploring Francophone (French-speaking) and Lusophone (Portuguese-speaking) works of literature and bringing them into the wider conversation. As an Afro-Lusophone myself from Guinea-Bissau, I waited eagerly. Years later, I’m still waiting.

Afro-Lusophone writers, in contrast to Anglophone and Francophone writers, remain conspicuously absent from the world literature scene. Anglophone writer Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie is now a global star, with her latest book, Americanah,on everyone’s lips and her speech “We should all be feminists” on Beyoncé’s Flawless. Publishers and editors from the West were scurrying in search of African writers, feverish not to miss the opportunity to bank on the Chimamanda effect. Similarly, Francophone writers are gaining currency with Fiston Mujila winning the Etisalat Prize and Alain Mabanckou long-listed for the Man Booker Prize. However, Lusophone writers remain absent from panels, festivals, discussions and debates. Whenever I confront people about the absence of Lusophone writers, they laugh nervously and say, “It’s the language.” But if books in other languages have been translated, why not books from Portuguese-speaking Africa?

The dominance of colonial languages in the African continent has created barriers between neighbors. So much time is spent perfecting the English language in Ghana that one does not learn Kwa languages or even French to communicate with French-speaking neighbors in the Ivory Coast. These barriers have extended to the literary market. Furthermore, African writers are still more interested in being published in Europe and the U.S. rather than across Africa. A Senegalese writer will not think of publishing in South Africa; Paris will be the first thing on his mind. A Kenyan does not seek literary agents in Angola; he will go to London before anywhere else. A Mozambican will prefer to go to Lisbon’s Book Fair instead of the Lagos Book Fair.

Such discrete borders can and should be diminished, and I have seen the importance of this in my own life. I was born in Lisbon to Bissau-Guinean parents and spent most of my life in Francophone Africa. My eager parents spoke only “Victor Hugo’s” French to me and my siblings. In my grandfather’s house, we spoke Portuguese with all the “R’s” sometimes interrupted by my grandmother’s Crioulo. My mother’s brothers, two suave hipsters who wore Doc Martens before it was cool, mixed Spanish and Italian while teaching me and my sister the delights of lasagna and cannelloni. At the age of 6, I added to my growing world of languages: American English, courtesy of Cartoon Network. I have grown up mixing, playing and inventing languages.

Continue reading the essay HERE.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions