Poetry is my effort to dialogue with a part of me that questions the sanity of the world.

— Chielozona Eze

***

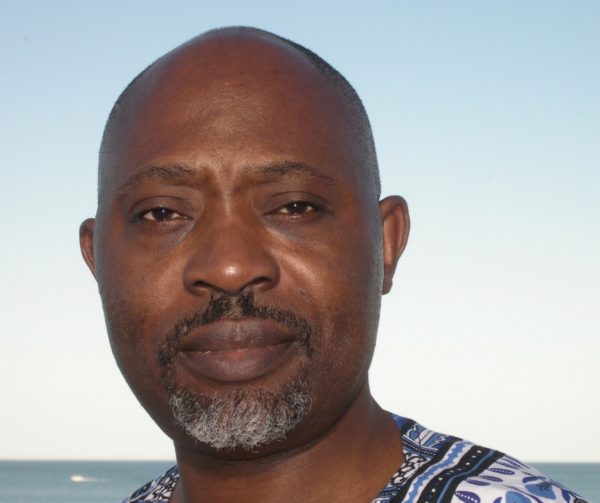

Chielozona Eze is a professor of English and African literature at Northeastern Illinois University, Chicago. He has had his writing published online and in print journals. He was shortlisted for the inaugural Brunel University African Poetry Prize in 2013. His chapbook Survival Kit was published by Akashic Books through the African Poetry Book Fund initiative in 2016. He has a new poetry collection titled Prayers to Survive Wars that Last (2017). I sometimes ponder how the past continues to haunt our national psyche. The past seems to have a way of iterating itself in spectral crises that beset our collective dream. Efforts aimed at forging a genuine nation usually appear chequered. Think of Biafra and its insistence. Think of the refugees in Borno State. Think of the generational trauma that attends to dispossession and dislocation and how it craves dialogue and amelioration. Reading Chielozona Eze’s Prayers to Survive Wars that Last, I wonder: How does one remember? What does it mean to remember? What fears haunt the refusal to converse with memory? Perhaps what some ghost simply needs is to have you just listen. It is within this moment of reflection that I decided to ask Eze for an interview, to which he graciously acquiesced.

Uchechukwu Peter Umezurike

It took many years for you to put together your debut collection of poems Prayers to Survive Wars that Last (2017), though your reputation as a poet was never in doubt among the Nigerian literati. Can you describe your own experience of writing the collection? How do you go about writing a poem? What determines the form the poem will take?

Chielozona Eze

Writing is tough. It is more so when you cannot support yourself from that. Judging from my day job, I am a philosopher and literary scholar. That means that what occupies my mind each time I wake up is how to shape my ideas in ways that can see the light of day and help me keep my job. In this regard, it is securing tenure and promotion. It surely took me a while to put together the poems in that collection because of the stated fact. Of course, I see myself as a poet, among other things, but poetry is just another way to engage the world – that is, another way to express some of the ideas in your head. There are certain ideas that are best expressed in unconventional formats, for instance, in ejaculatory, incantatory, descriptive, narrative, or other formats. Surely, every effort to address oneself to the world begins with an idea. I know that a particular idea recommends itself to poetic form if I can visualize it, if one image can immediately capture the feeling I want to share. Once that is fixed, then all that is required is to find appropriate words and rhythm to carry that image. Actually, every poem determines its shape. It is like a child coming out of the womb. Even if you don’t like what has come out of your womb, you try to nurture it until it leaves your house and makes its own way in the world.

Umezurike

I recall watching a clip of Lucille Clifton talking about poetry as I read your collection. Poetry, Clifton says, offers her a way of “trying to express something that is very difficult to express, a way of trying to come to peace with the world.” As a survivor of the Nigerian-Biafran civil war, how has poetry helped you to grapple with political horrors such as ethnic cleansing, pogroms, refugee crises, and so on? What is the work of poetry, if any, in a time of horror – as is the everyday reality of many people in our world today?

Eze

I love Clifton, and I agree with her notion of poetry. Besides that, poetry to me is like saying a silent prayer you know will (or perhaps might) never be answered. But you know that if you do not say that prayer you might lose your senses, or go nuts—as my students would say. Poetry is my effort to dialogue with a part of me that questions the sanity of the world. Poetry can never (or perhaps hardly) stop the horrors of the world. It can, however, teach some people to begin to feel the world differently and to have enough dose of humanity to nip such horrors in the bud. I never believed in the revolutionary powers of poetry. But I hold the hope that some lines in my poems might make some people smile or bring them to some good thoughts.

Umezurike

Uche Nduka, a contemporary of yours, says, “To be a poet is to understand that a poem is a moving target.” What defines a poem as a poem for you? And what does it mean to you to be a poet?

Eze

You might recall the parable of the sower in the Bible. I think Van Gogh has a wonderful rendition of that parable in painting. A poet is the sower and a poem is like one of the seeds. Some seeds are eaten by birds as soon as they are sowed. Some germinate, but they are choked by weed. Some seeds lie dormant for years and then they suddenly find favorable condition for germination. Of course, some seeds are lucky to find fertile soil.

Umezurike

I could feel the pain of reunion between mother and son, country and citizen, in the poem “The art of loving what is not perfect”. However, the following stanza evokes a sense of fatalism, even as the poet persona expresses some resolve. Can you recollect what you were thinking of when you wrote this particular poem?

I learned from the worms

to wend my way in wet and dirt.

I know that any day could be the end.

Until then, good Lord, I trudge on, I.

Eze

Perhaps the fatalism you see in it is just the bareknuckle fact of making peace with mortality and finitude. It might have issued from my love of Nietzsche’s amor fati, love of one’s fate. I think you become a happy human being the moment you admit the fact that you are not a genius, not an angel; the moment you accept that you are not extraordinary and you don’t even need to be so in order to be human and to be relevant in your society. Some people, I’m sure you know a bunch, would go about broadcasting how great they are, how ingenious their minds are, but they wouldn’t relate to their next in most human and humane way.

Umezurike

The opening couplet in the poem “Memory: a prayer” makes me think of the ways the Nigerian state has continued to resist appeals to remembering and modes of acknowledging the trauma of the civil war. The couplet reads thus: “To remember is to reach into a fire/to save a letter for you in a foreign tongue./You could be burnt again if it’s translated.” Can you share your inspiration for the poem? How might poetry, in its potential for unveiling and unsilencing muted histories, help us to recognise the need to listen to the Other, even when it is a ghost? A spectre haunting our collective dreams of nationhood? What, in your view, is at stake for the Nigerian state in assuming this position?

Eze

I find difficult to address states. I don’t. It’s a waste of time and talent. And it is a sophisticated way of avoiding personal responsibility. Rather, I address myself. I address a few others who might derive inspiration from my words. I address others who are as educated and enlightened as I am. Regarding the Igbo experience of genocide and war, it would be foolhardy of Igbo to expect those whom they accuse of genocide to keep memory of that incident alive. Hello! Common sense should tell you that it doesn’t work that way. The responsibility of keeping the Igbo experience alive falls on the Igbo, specifically, on their educated class to which I belong. But memory is a dangerous thing. There is always the temptation to be selective, to remember what was done to you, but not what you did to yourself or to others. I am, indeed, interested in how intellectual and moral adults among the Igbo respond to that phase of their history.

Umezurike

The poem “Stocktaking” is full of rhetorical questions. A case of “to remember or not to”. Can you say just a few words about the stanza below?

Of what use is it to take stock

of what we ate or did not eat

and that we nearly died from both?

Eze

I suffered kwashiorkor. But I also ate many things I wouldn’t even touch today. A certain stinking grasshopper called oshinaka was a treat, as were lizard and rats. Many people died after consuming certain kind of mushroom. So, if you ate something, you die; if you did not eat, you still die. That was our experience then. By the way, I was five years old when the war began. You know it lasted thirty months. Some people remember these things with hatred in their hearts. I don’t have a space for hatred or even for blame. That’s why I don’t take stock of what was done to me or the evil I experienced. I know that I am alive today. And I am happy. That means a lot to me.

Umezurike

I was taken by the poem you addressed to Afam Akeh. I really liked Akeh’s Letter Home and Biafran Nights (2012), and I remembered he said that “memory is not always friendly.” This quote, for me, illuminates the poet persona’s lament in your poem “Letter to self from a city that survived”. Can you speak more about this particular poem? And what influenced might Afam Akeh have had on you as a fellow poet – or your poetics?

Eze

Afam, as you know, is good poet. He’s one of those poets whom you’d want them to be putting something out here because there will always be some profound insight. I loved Letter Home and Biafran Nights (2012). I think two of us might be the same age. Not quite sure. Yes, I was inspired to write that particular poem after reading Letter Home and Biafran Nights. I might have reviewed the collection. Every poem in that collection has at least one nugget of intense feeling or deep ideas that inspire.

Umezurike

“In search of my father’s dreams” struck me in a personal way. It makes me think of how children embody their parent’s trauma in some way. I particularly liked the lines:

I’m not the one that speaks when I speak;

Thousand tongues meld in my mouth.

For them I demand an answer.

What insight have the “school of pain” offered you? How much of the pain have you been able to shed?

Eze

Great question. School of pain has taught me to begin to appreciate myself and others. Simple. I don’t want any person to go through the pain I have experienced. Yes, I have shed my pain and disappointment. I’m lucky in life. I really can’t complain. I’ve met wonderful human beings. Some of them went out of their way to help me, even though they didn’t know me, For example, the war, my family was plunged into abject poverty. I was literally adopted by the Catholic Church. It paid my school fees from secondary school up to my master’s degree in Catholic theology. It send me to Austria to study with the Jesuits. But even before then I met the first white people in my life in one of the many refugee camps scattered in Igboland. They brought us food and medicine that saved my life. The good and beauty I have experienced in life far outweigh the evil. So, why shouldn’t I count myself as a happy graduate of the school of pain? If you have survived such pain, the only thing you owe the world is love.

Umezurike

How has your training as both a philosopher and an academic shaped your poetry? Would you have appreciated poetry differently if you didn’t have such a training? How does this affect you as a poet? And how do you balance teaching, literary criticism, and writing poetry?

Eze

… and Catholic theology! Yes, it is wonderful, on the one hand to draw ideas from these different disciplines. At times they help me to see an idea from different perspectives. On the other hand, it can also be tough sometimes to have ideas and inspirations from these different disciplines that compete for attention in your mind. I’m no longer a practicing theologian, but I’m a philosopher and literary scholar. It’s tough to combine these with writing poetry. The more you analyze other people’s poem for the purpose of composing essays the less courageous you are about putting out your own ideas.

Umezurike

Can you say a few words about the current state of poetry in Nigeria? And the African Poetry Book Fund which published your chapbook, Survival Kit (2016)?

Eze

I think current state of poetry in Nigeria is good. I am particularly happy that most poets are not as invested in meeting the gaze of the West as some novelists. They are also not interested in what I call lachrymal poetry of Oguibe generation. I love especially the poetry of Chijioke Amu Nnadi, Ikeogu Oke, Romeo Oriogun, and many others I can’t remember right now. What I regret is that we don’t have any review outlets where the works of these poets could be “explained” to people. As a matter of fact, only Ikhide Ikheloa seems to be doing such works of reviews yet we have at least ten Nigerian professors of literature in my generation. We could do more …

Umezurike

What poets are important to you as a poet? Are there particular authors who have meant a great deal to you since you started writing poetry? Finally, what might you be working on next?

Eze

There are many. Czeslaw Milosz is really important to my thinking as a poet. He is accessible and he is deep. Most importantly though, each time I read his poems I want to write mine. I’m no longer writing poetry. I might get back to it sometime. Currently, I am writing a book on contemporary African poetry.

**************

Buy Prayers to Survive Wars that Last | Amazon

***************

About the Interviewer:

Uchechukwu Peter Umezurike is a PhD student at the department of English and Film Studies, University of Alberta. His research interests include postcolonial literatures, print culture, gender and sexuality studies. An Alumnus of the International Writing Program (USA), his work has appeared in several print anthologies such as On Broken Wings, Dream Chasers, Migrations, African Roar 2011, Daughters of Eve and Other Stories, Work in Progress & Other Stories, A Generation Defining Itself (Vol. 8),Weaverbird Collection, New Nigerian Writing, Water Testament, Calvacade, Author Africa, and Camouflage, etc.

Uchechukwu Peter Umezurike is a PhD student at the department of English and Film Studies, University of Alberta. His research interests include postcolonial literatures, print culture, gender and sexuality studies. An Alumnus of the International Writing Program (USA), his work has appeared in several print anthologies such as On Broken Wings, Dream Chasers, Migrations, African Roar 2011, Daughters of Eve and Other Stories, Work in Progress & Other Stories, A Generation Defining Itself (Vol. 8),Weaverbird Collection, New Nigerian Writing, Water Testament, Calvacade, Author Africa, and Camouflage, etc.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions