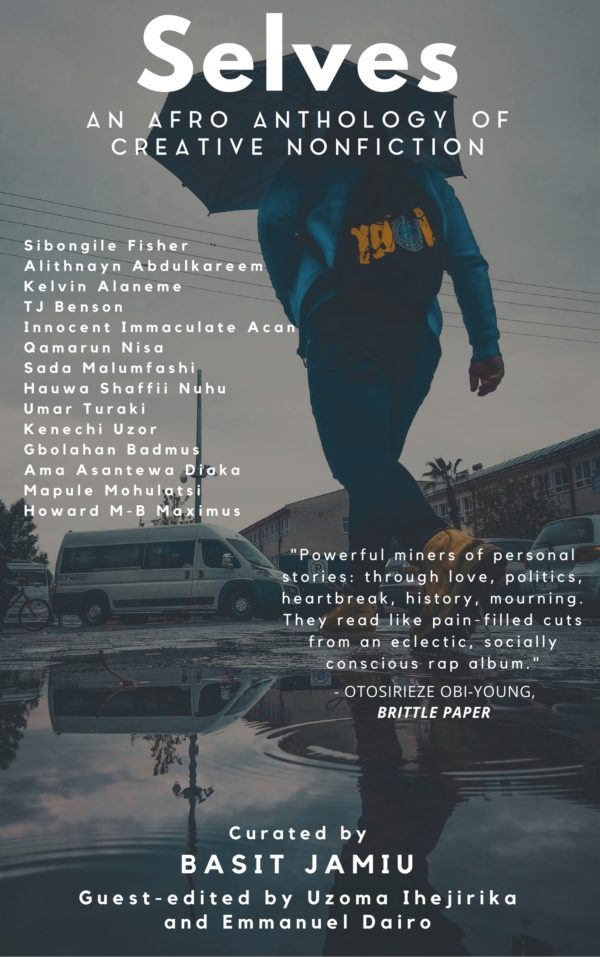

In February, we published Selves: An Afro Anthology of Creative Nonfiction. Curated by young Nigerian writer Basit Jamiu and introduced by Brittle Paper deputy editor Otosirieze Obi-Young, the anthology collects creative nonfiction and essays from writers across the continent. We recently republished one of the pieces: Mapule Mohulatsi’s “The Nervous Conditions of the Mother Tongue.” Here is a conversation between the anthology curator Basit Jamiu and the anthology cover creator Tope Akintayo.

Basit Jamiu is a fiction editor at Enkare Review and curator of Selves: An Afro Anthology of Creative Nonfiction. He is on Twitter with (@iambasitt). Tope Akintayo is the curator of Witsprouts. He is on Twitter with (@topeakintayo).

DOWNLOAD: Selves: An Afro Anthology of Creative Nonfiction

Tope Akintayo

What was your first encounter with the literary community? What age were you then, how did you come into it, in what way did you respond to it—was it something like an Eureka moment when you just knew your heart belonged in the literary world, or was it gradual? I’ll love you to mention some names and works that constitutes these encounters.

Basit Jamiu

I grew up in a place and home where literary consciousness was not a thing. As a child, I read a lot of books, mostly borrowed from friends. I attended an Islamic and Arabic secondary school and I was surprised that the school, although it had existed for more than thirty-five years, had no social or intellectual group. I created a platform where students like me could sit and talk about their favourite stories and exchange stories too. I noticed that my hunger for stories was insatiable. As the group became established, we began to read news at the assembly ground every Monday and Friday. There was also an Update Board where students could just go and read news updates, poems, and stories. To learn the intricacies of social groups, we visited other secondary schools. It was through these visits that we agreed that our group should be named “Press Club” because the name was close to what we were doing at the time. The group has been in existence for 9 years now and it is a group for the brightest students in the school. I get to visit them when I am at home and I am moved by the level of creativity and ingenuity, and the beautiful projects that they are always working on. On the other hand, if there was really anything like an e-literary community, which I believe is not like the traditional literary community as we know it, then I have to say, it is hard to recall the exact period I became conscious of this literary community that you have asked about. I joined Facebook at the age of 16. I think the whole thing was a happenstance. As the years added on, it formed on its own and I wasn’t really conscious or thinking about its development or metamorphosis. I joined social media like most people, to connect and enjoy some of the luxuries that the media affords. I think along the way I found other people who shared my interest and passion and then we became connected that way too.

Tope Akintayo

One of the things I admire about your Facebook profile is this: I think of your wall as the Hacker News for smartness—an aggregate of intellectual stimulation. Do you actually read as much stuff as you share, and how do you even keep track of those websites and publications? Do you kind of had them all bookmarked or what?

Basit Jamiu

Yes, I do. I read everything I share. I started the idea of sharing literary links not because I was thinking that my friends would be interested in what I share but because I wanted to save the pieces that I have read for later rereading or accessing. I share little percent of what I read. Between 15% to 20%, I guess. I share only the pieces I wish to go back to reread someday. I have a few websites that I go to for literary juice, cultural or political updates: The New Yorker, Granta, The Guardian UK and Brittle Paper are amongst them. Often, when I am interested in a particular subject or theme or a particular writer, I google it, read as much as I can get and then share some that I would like to reread later.

Tope Akintayo

More about the Community of writers and readers you talked about. What was your aim of starting it and how is that aim being met so far? What has been the level of reception and participation too?

Basit Jamiu

I came to EKSU as an undergraduate in 2013. I searched for a literary community where I can get to meet people whose passion is similar to mine and I didn’t find any so I created one with friends. And we were dazzled by the amount of students that showed interest as soon as the literary community was accredited. I wanted to create a platform where I and others could just sit down and talk about reading and writing, but then as the years gradually moved further, it became a literary community with a lot of influence in the campus. We organised debates, literary competitions, literary workshops. When I look back now, five years on and I am still amazed with what the community was able to achieve. I wanted a platform for me and every undergraduate in search of a literary community, and I am happy that we were able to achieve this and more.

Tope Akintayo

I’m this kind of person that loves to hear stories of metamorphosis and becoming a lot. I love to dig deep into the stories of how the people doing great things came about it. So I’m curious about your position at Enkare Review. What relationships or encounters led you to that position?

Basit Jamiu

I was on Facebook one day when Troy Onyango, a brilliant writer from Kenya, told me that he had been following me and he was hoping that I would join Enkare Review as Fiction Editor, and I said yes. Enkare Review is a magazine I love so much. I was amazed with the caliber of writers and pieces that they published—Junot Diaz, Leila Aboulela and Nnedi Okorafor—before I joined the team. Being a part of the Enkare Team has been epic and transformational for me.

Tope Akintayo

Recently, in your status on WhatsApp, you wrote about someone asking you what it’s like to be an editor. What is it really like being an editor?

Basit Jamiu

The role of an editor, in the case of literary works, is to see that a piece of work is better than it was. In the case of reading through submissions and entries, the editor will have to be someone with an eye for quality works. Being an editor, particularly for a reputable magazine like Enkare Review, is pretty tasking and time-consuming, but it can be fun too. I like to say that being an editor is like someone who has been assigned to feed the whole continent with a good meal; I don’t think you would want to feed these people with undercooked or salty jollof rice, for example. One has to make sure that the food is well-cooked and sweet enough to be served to the eager and waiting audience.

Tope Akintayo

What was your first reaction when you saw your name on YNaija‘s “2018 New Establishment List”?

Basit Jamiu

It felt nice to be listed, at the age of 22, among “young Nigerians at the cusp of greatness,” and I really hope that I can continue to produce substance and value out of my little ideas. I hope that I can continue to make Nigeria, Africa, and the world better than it was till I am no more.

Tope Akintayo

How did you pull Selves off? I’ve been a part of the project from the beginning but I am really curious about the mechanism behind the whole thing. How did you get the contributors to agree to write? Did you do cold emailing? What were the responses like?

Basit Jamiu

Selves is born out of idea that we need narrative nonfiction from African writers that will speak to people the same way that good fiction can. It was also an idea to fill a literary space in Africa, an often uncharted pathway, and it became the first independent anthology to collect nonfiction works from the continent. The idea came to me one morning and I began to work on it immediately, reaching out to some of the best young writers in the continent. It took us over a year, I and my team, to make the pieces that we’ve received from these brilliant writers into a book. It was the most difficult project I have ever worked on and I am happy with the huge reception that greeted the anthology. It somehow made all the sleepless nights, the anxiety and the countless emails during the day worth it.

Tope Akintayo

So you reached out to, in your words, “some of the best young writers in the continent,” which I guess wasn’t an easy task. I’m particularly interested in that process of reaching out to these writers. I want to believe you’ve never spoken with some of them before that time. What were the difficulties you experienced with reaching these people. That’s why I mentioned the cold calling. When you sent out those emails and messages to the writers in your list, did you get replies from everyone, were all the replies positive, and do you think that some of the positive replies are due to your position at Enkare Review?

Basit Jamiu

The process that you are asking about is a long one and it is hard to answer your questions in a few lines. I think I will write an article about this and hopefully you will get to read it. This project took us over a year. I have spoken with some of the writers before, but I have never spoken to most of the writers that I worked with on the anthology until I started the project. And yes, the replies were all positive and I am not sure if it was because of my position at Enkare. I believe it has to do with the authenticity and significance of the project to Africa’s literary space.

Tope Akintayo

So now you’re the curator of a phenomenal literary project and also an editor at a significant literary magazine. I’m thinking that there might be a correlation between those two titles. A curator, an editor. Do you think there’s any relationship between the two, and is there one you feel you are better at?

Basit Jamiu

There are so many connecting and dividing lines between an editor and curator. I enjoy doing both; editing and curating. One of the connecting lines is that these two jobs are very time consuming.

Tope Akintayo

I guess so much that you’re the kind of reader that balances consumption of western literature with a good dose of African literature and vice versa. How often do you read western literature compared to African literature? And can you say that you’re complementing one with the other, say, there is an element lacking or available sparingly in western literature that is abundant in African literature, and vice versa?

Basit Jamiu

I read books that I find important and interesting and it doesn’t matter where they are written or who wrote them.

Tope Akintayo

Several times, I’ve seen you share on Facebook the music you’re currently listening to. Sometimes you’re listening to Drake’s “The Six” and other times you’re listening to Runtown’s “Mad Over You.” Sometimes you share some music you’re listening to and I’ll be like “Wow, he listens to this kind of music!” I mean the kind of music that many folks on Facebook would criticize for bad lyrical content, swearing that they’ll cut off their own ear if they happen to hear it being played in the street. But there you are, glorying in your choice. So I wonder how you make your choice of music. What’s the influence of music lyrics and melody for you? And also what’s your take on the criticism of music based on the quality of its lyrics?

Basit Jamiu

The beauty of any song is not restricted to its lyrical quality. It goes way, way beyond lyrical maturity or beauty. You can enjoy a song in Portuguese without even understanding a word in Portuguese. Every music has something that makes it beautiful. I have a taste for all music I guess. Music has its own universal language and beauty; music is the only magic that has survived the growth of time and the only thing that will outlast time.

Tope Akintayo

Thank you for your time, Basit.

Basit Jamiu

It’s my pleasure, Tope.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions