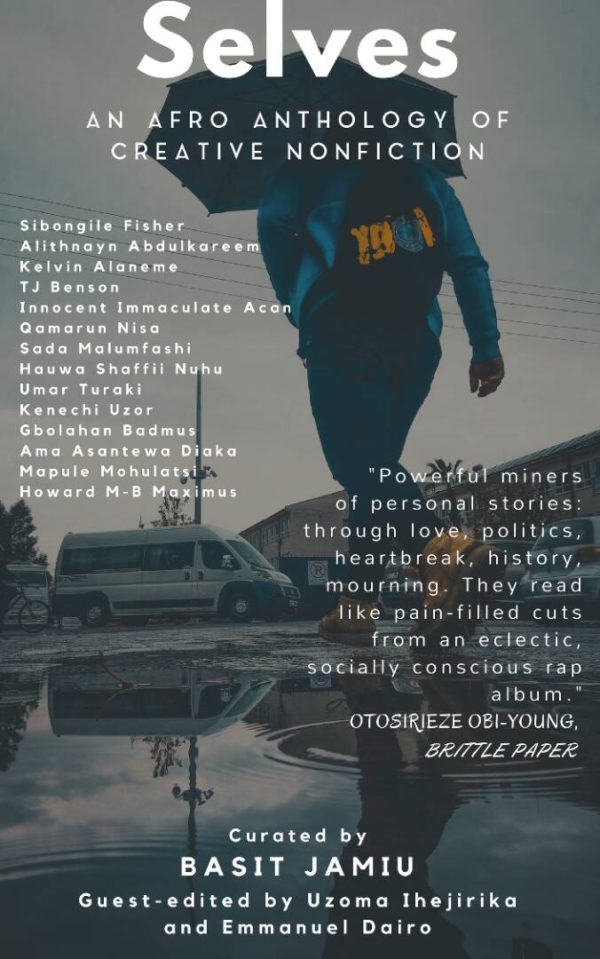

Selves: An Afro Anthology of Creative Nonfiction is a forthcoming anthology of creative nonfiction, curated by Basit Jamiu and featuring writers from across the continent. Its cover is by Tope Akintayo. One of the pieces from it—“The Miseducation of Gratitude,” by Sibongile Fisher—recently appeared in Enkare Review. Selves is introduced by Brittle Paper deputy editor Otosirieze Obi-Young.

_________________________________________________________________________

The Confessional Generation

In her introduction to Safe House: Explorations in Creative Nonfiction (2016), the collaboration anthology by Commonwealth Writers and Cassava Republic which has become a major point of reference in this genre, the editor and critic Ellah Allfrey observes that, relative to fiction, creative nonfiction from Africa is “in a germinal phase.” It is a safe observation; but from the anthology came Hawa Jande Golakai’s “Fugee,” a witty, affecting interrogation of the Ebola crisis in Liberia. And later that year, from Granta, came Pwaangulongii Dauod’s “Africa’s Future Has No Space for Stupid Black Men,” an electrifying, defiant account of an underground LGBTIQ club in Nigeria. The following year, from Granta also, came Binyavanga Wainaina’s “Since Everything Was Suddening into a Hurricane,” a groundbreakingly innovative rarity. These three works were shortlisted for the inaugural Brittle Paper Award for Creative Nonfiction, and side by side with the other shortlisted works—Bernard Matambo’s “Working the City,” a poetic tale of visa application; Rotimi Babatunde’s “Out of Germany: Traveling with the Caine Prize,” a poignant re-visitation of history; Bethuel Muthee’s “Naijographia,” a psychogeographical exploration of Nairobi; Oris Aigbokhaevbolo’s “Uniben Boy in Berlin,” a juxtaposition of cities; and Troy Onyango’s “How It Ends,” a beautiful behavioural study—reveal the promise of something more in the genre: range. So that I find myself leaning away from Allfrey’s suggestion, and agreeing with Kwanele Sosibo’s conclusion, in his Guardian & Mail review of Safe House, that “creative nonfiction on the continent is past the germinal phase.”

But to agree with Sosibo is not to play down Allfrey’s wording: because creative nonfiction, as far as the establishment of stable literary traditions is concerned, is still growing, partly because creating nonfiction requires travel and research which in turn require funding and funding is a major problem in African publishing, then partly because there has been no book in the genre to capture the imagination of literary audiences enough to secure interest and trust in it. For this century so far, there are references—Aminatta Forna’s The Devil That Danced on the Water (2002), Faith Adiele’s Meeting Faith: The Forest Journals of a Black Buddhist Nun (2004), Binyavanga Wainaina’s One Day I Will Write About This Place (2011), Noo Saro-Wiwa’s Looking for Transwonderland (2012), Teju Cole’s Known and Strange Things (2016), Sisonke Msimang’s Always Another Country (2017), Chike Frankie Edozien’s Lives of Great Men (2017), Panashe Chigumadzi’s These Bones Will Rise Again (2018), Emmanuel Iduma’s forthcoming A Stranger’s Pose (2018)—but there aren’t many, and there certainly aren’t more than a few that aren’t memoirs. The skill is here, the willingness in abundance, but the tradition, when compared to what has been in fiction and has been revitalized in poetry, is still emerging, like the newest generation of writers on the continent who, remarkably, have taken to it.

The contributors to Selves: An Afro Anthology of Creative Nonfiction belong to this generation. Aside from their skills having been honed on the continent rather than in the West, these writers stand out for their boldness in expressing themselves, for their lack of fear in, to paraphrase Henri J.M. Nouwen, going where it hurts. Powerful miners of personal stories, theirs is a confessional generation. In general, you will find them on social media emoting boundlessly, sharing the spoken and unspoken, their lives an invitation for participation. In particular, you will find that they write fiction well, have breathed life back into the poetry scene, but that it is in nonfiction that they are unshackled, unspooling confessions in a hitherto unconventional manner. Through emotional honesty as raw as it is brave, they are taking the genre to places their predecessors shied away from, leading important conversations about trauma, about sex and sexuality, about depression and vulnerability and private shame: Take a look, for example, at the catalogue of Nigerian emotions published in Catapult since last year.

Firm in this new tradition, the pieces in Selves flit from the flourishing creative to the tonally essayistic, but they all share one thing in common: heart. Force, intellectual and emotional, that moves: through love and heartbreak, through politics and history, through death and mourning, in depression and humour. They read like pain-filled cuts from an eclectic, socially conscious rap album: Sibongile Fisher’s sure-footed, poetic reinterpretation of Lauryn Hill’s 1998 album frames a soulbreaking autobiography of love, motherhood, family, and wounds; TJ Benson affectively strings bits of personal history while tracing his fear of water; Sada Malumfashi takes us on a raving tour of both a city and a man, and in prose punctuated by memorable lines; Umar Turaki revisits, through a plural perspective, his father’s demise to raw effect; Ama Asantewa Diaka feels, in grief-laden breakups and visitations to a gynaecologist, for healing; Gbolahan Badmus elevates his teeth to character status in a vulnerable, often-humourous reminisce of childhood and adolescence.

Mapule Mohulatsi offers an ethno-lingual survey of her South African upbringing, reflecting remarkably on the seminal power and inseparability of writing and the tongue; Qamarun Nisa probes for self-discovery while weighing depression and the meaning of resigning one’s body to powers from without; Kenechi Uzor confesses literary and political disappointment, similarities and discrepancies between his home country of Nigeria and the U.S.A.; Hauwa Shaffii Nuhu deals with the pain of losing a mother-like aunt; Alithnayn Abdulkareem sums up her Muslim family’s distrust of her free-spirited millennial daughterhood; Kevin Alaneme recounts the disaster-by-disaster horror of ordinary Nigerians in the face of Boko Haram’s atrocities; Howard M-B Maximus recollects a childhood dominated by his father; Acan Innocent Immaculate reclaims the beauty of her dark skin and its centrality to her identity; and Adams Adeosun uses a visit to a coffin-maker’s to guide an unsentimental reflection on existence.

These fourteen are the pieces in the e-book publication of Selves on Brittle Paper. To them, this print publication adds ten more, each pulsing with a different side of life: Vuyiswa Maluleke occasionally breaks into sharp poetry to tour a body spinning in a family, “writing beside doubt and often across from myself”; Chinaecherem Obor searches to grasp faith, through existential questions around God and madness, through efforts to triumph over the homophobia of his past; Afopefoluwa Ojo places us in a triangle of the self, love, and religion; Victor Daniel invites us into a suicide survivor’s efforts to wean himself off depression pills; and Oris Aigbokhaevbolo begins with a standout paragraph, treating us, in chatty, chewable prose, to a visit to Geneva, a rumination on cultural quirks, and centrally, a meeting with an object of admiration: the novelist Petina Gappah.

Jennifer Chinenye Emelife awakens us to a poet luring his female protégée into a sexual relationship, raising painful questions of sexual molestation; Adefolami Ademola confronts his difference, a peculiar inability to sustain love and commitment, and a struggle to accept a child he is deceived into fathering; Tolu Daniel closely observes a man whose passing then leads him into a crucial story of the man’s life as well as truths in his own; Eugene Yakubu uses their body to ponder the heteronormative binary of male/female, reiterating the uncompromising existence of the Third Sex, because: “He, she, you can call me anything, but just so you know, a rose by any name will still scent the same.”

In suggesting the order of appearance of these works, I felt strongly that a definitive book as this should end with a definitive work. It is fitting that this anthology is closed by Megan Ross’ post-childbirth pondering of motherhood in her lineage, an extension of the meditation began in her sumptuous poetry collection Milk Fever, and in that flowing-spring prose for which we have come to know her. It is as close to technical completeness as can be; it frames an unstated argument that, here, in this book, these two hundred-plus pages, a set of artists have made a stand on their own talent—that their skill set matches some of the best out there, with or without recognition. What a shame, these pieces murmur, what a shame that we often look in the wrong places for vibrant new voices.

That we have Selves is down to the rise of independent anthologies on the literary scene: projects curated without affiliation to magazines or publishing houses, by young creatives unwilling to be held back by the absence of funding or the presence of gate-keeping, but which still boast quality. The queer art collective 14’s We Are Flowers (2017) and The Inward Gaze (2018); Art Naija Series’ Enter Naija: The Book of Places (2016) and Work Naija: The Book of Vocations (2017); the romance-themed Gossamer: Valentine Stories (2016) and Love Stories from Africa (2017); and the thematically-diverse A Mosaic of Torn Places (2017): these independent projects, published as free e-books on Brittle Paper, have all been well received, with the first four creating space, in addition to writing, for stunning visual art. In this sense, theirs, ours, is also a Fighting Generation—fighting to be seen, in a culture that grants visibility firstly to the privileged, fighting for their talents to be let to speak for themselves, against a system that prioritizes class over substance, prioritizes the stature of artists over the stature of art. But the space into which Selves steps into is partly uncharted: It just might be the first independent anthology to gather only creative nonfiction from across the continent, and now, it is the first to go to print, to try to break into traditional publishing systems which, ironically, would have kept it out at first. The curating here by Basit Jamiu, an editor at Enkare Review, is applaudable, but even more admirable is the hunger with which he pursued it for one year—first to get it released as an e-book, and now to get it released in print—that decisive hunger to fill a gap. Working with him on this project has been as revelatory and enjoyable as it has been tasking.

However, that this is a celebration of short nonfiction should sustain the interrogation of why a continent’s literatures do not yet boast more long-form, book-length nonfiction. This is where Allfrey’s words cannot be stressed enough: without books by single authors, even with anthologies as remarkable as this, the culture of creative nonfiction would remain “in a germinal phase.” Here is to hoping that the writers in this book may one day lift it all into full-length works.

You may cry, you may laugh, you will learn: You have in your hands a loud, pungent reminder of the unnegotiable importance of personal stories, their potential for transformation, their channeling into art, into fractured, crystalline multiples of their creators’ beings. Selves is an invitation to partake in a ripening promise, a step into years to come.

I am greatly honoured and excited to offer a guide into this book.

About the Author:

Otosirieze Obi-Young is Deputy Editor at Brittle Paper. His fiction has appeared in The Threepenny Review and Transition, and has been shortlisted for the Miles Morland Scholarship and the Gerald Kraak Award in 2016. The curator of the Art Naija Series (Enter Naija: The Book of Places in 2016, Work Naija: The Book of Vocations in 2017), he teaches English at Godfrey Okoye University, Enugu, Nigeria.

Nigerian Literature and the Era of the Nomadists | Open Country Mag August 17, 2023 12:19

[…] Afro Anthology of Creative Nonfiction, christened a crop of young African nonfiction writers “The Confessional Generation,” due to their being “unshackled, unspooling confessions in a hitherto unconventional […]