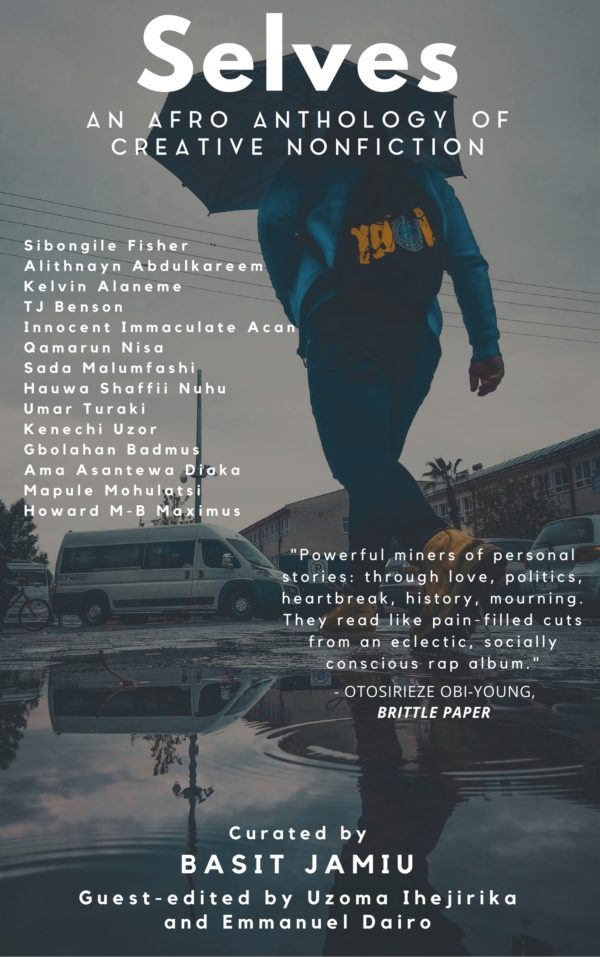

We are republishing select pieces from Selves: An Afro Anthology of Creative Nonfiction, curated by Basit Jamiu and introduced by Otosirieze Obi-Young. Here is Mapule Mohulatsi’s “The Nervous Conditions of the Mother Tongue.”

DOWNLOAD: Selves: An Afro Anthology of Creative Nonfiction

*

“I know nothing that has as much power as a word.

Sometimes I write one, and look at it, until it begins to shine.”

—Emily Dickinson.

1.

I WAS BORN on the edge of South Africa’s national freedom—it was on the 4th of December 1993 at the Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital in Soweto. This hospital, my first (not so humble) abode on earth, was opened in 1942 as an Imperial Military Hospital for the black population after the Second World War. It became known as the Chris Hani Baragwanath Hospital in honour of Chris Hani, a former leader of the South African Communist Party (SACP), after his assassination, also in 1993. It is the largest (and probably the bloodiest) hospital in Southern Africa. In the enigmatic year of my birth, the Sunset Clause: South Africa’s peaceful Walk to Freedom, was already in motion, introducing an oncoming and negotiated democracy. By then, the tabula rasa of what constituted African literature had already been smeared by debates on the language question by the bearded thinkers of our continent.

The sweet promise of democracy convicted my mother’s womb, and the other women who were also pregnant at the time, to an electrified rejoicing, a roused ululation at the idea of us: the children “born free”. To the heavy women at the Baragwaneth maternal ward, it had already been unanimously decided that these children, with the fruits of freedom and education waiting for them, would learn to pray in their mother tongue(s); escaping the wrath that had been imposed upon their mothers by Bantu Education. Many of us were christened with African names, but of course, our second names were English, just in case. Yet, despite the aesthetic of our names, secretly, our mothers, or at least my mother, also fantasized of the crystal-clear English I would grow up to speak in the New South Africa.

Writing this, I am actively imagining the frustration my mother must have felt when a pre-school report I brought home praised my confidence and creativity; yet, the blue report card also briefly advised that it would do me a great good to practice speaking English at home.

P-r-a-c-t-i-c-e:

The actual application or use of an idea, belief, or method, as opposed to theories relating to it; Repeated exercise in or performance of an activity or skill as to acquire or maintain proficiency in it

— Oxford Online Dictionary.

At the tender age of six my mother and I tried to practice speaking English at home as advised by my pre-school teacher, but often reverted back to our home language due to the alienation our tongues felt—slipping and falling, seeking the right word, losing the idea—until we eventually gave up this practicing of English at home.

However, good schooling, avid reading, and the racially-mixed friendships I maintained became practiced enough as I grew up. I am still practicing. My tongue seeks escape routes the entire time. My mind, however, has learnt to grapple and hold onto those lingual sentiments that pertain to the lunacy I will discuss here.

Most of my affiliations with language and writing are deeply rooted in the English language. And I am okay with it. It is uncomfortable that my country has now changed the course of its aspiration and has forgotten the dream of the blue report card.

2.

WRITING RELIES on language, yet it also has the ability to erase language. When Emily Dickinson writes a word, and then ‘looks at it, until it begins to shine,’ it seems that the particular word ceases to be a word; it becomes an insignia of [her] meaning; as if the word itself, the visual delicacy, exists solely to represent what is hidden underneath it, which is the thing ‘that shines.’

Pity then, that language and meaning have become the paraphernalia of the discourse of writing in Africa.

Firstly, to write any word is already an achievement the many who belittle you for your chosen career path should know about. But then again, illusions aside, you are in the modern African state where things aren’t as easy as they appear.

You are the oral, primordial, wo/man.

Orality has often been defined as the quality of being verbally communicated; many still believe that orality is the first phase in the pyramid of human history and literacy. The oral man is the primordial figure—the beginning of history. Orality, as Ruth Finnegan preaches in ‘What is Orality, If Anything?’ (1990), is seen as ‘representing the fateful development out of “primitiveness” through our acquisition of writing—together with all the supposed properties that have so often been assumed to go along with that division—”the Great Divide, between Us and Them”—a division which is thus so easy to associate with orality and literacy respectively.’ In the context of African literary and cultural production aesthetics, orality has often played the role of not diminishing this divide, but extending it. The construction of national identity through the oral narrative mode, evident in post-independence African writing, has set values of authenticity for individuals and how they should use ‘traditional’ conventions. This divide of the oral as traditional, and the written as modern, is a false concession to modesty and development; it devalues the relationship between storytelling and temporality, simultaneously degrading the temporal paradoxes of modernity.

Writing in Africa has generally been surrounded by such behemoth myths and rumours; in fact, the one myth that has been circulating since the advent of Social Darwinism is one that has infiltrated the literary course of a continent: Africans have no (written) history. Foolishness! It is this excavation of the skull of a continent that has led to ideas such as ‘since Africa has no written history, then all history that is African is oral’; that ‘since literacy in Africa was afforded by the colonial project, writing in the colonizer’s language perpetuates something.’

3.

I SIT AT the local bar, scared witless, trying to write. I imagine the entangling web of cutthroat opinion pieces that hover above those that can write—the ‘critical eye’. Then, before I can even take the next gulp of beer, the shadow of the consummate reader also loiters before me. Relax, I say to myself. I remind myself that writing is the holy practice where I can, and should, acquaint myself with the sentiments and instincts of writing; those early morning gut reactions, along, of course, with the varied contradictions of what really constitutes humanism and lingual lunacy.

I ask myself whether it is the tongue or the pen that writes.

My tongue is not wholly separate from the business of writing, especially, writing in English. In writing this, I am adhering to Karin Barber’s sermon in her ‘African-Language Literature and Postcolonial Criticism’ (1995), that:

Writing in English can be understood more richly if we abandon the picture of the colonial language as an all-enveloping blanket of repression, and the indigenous languages as stifled, silenced sites of muted authenticity and resistance. Instead, we should perhaps see English as one available register among others, in specific scenes of cultural production.

The evils of the discourse concerning language and writing in Africa linger ceremoniously above the shaking pen of the pundit-in-training (myself) as government of this true self that language supposedly ministers.

It is becoming uncomfortable to cringe in self-hate because I have little aspiration to write in my home language.

For me, writing often results in my tongue rolling in and out in rapid movements. And even though there is no scientific study of the tongue’s relation to writing, it is a definite side effect to have the mind roving endlessly in the jungle of jargon, wisdom, pronunciation, and witticism—not to mention the benchmark that hovers over the disfigured author of colour: History.

When I write, or at least try to, it seems that my tongue has a certain level of control over my mind; often, it looks as if the two have a cozy relationship, without me; ever so often leaving me out in the cold, meandering both my mouth and mind into battlefields where the landscape of cultural, linguistic, and postcolonial history glistens like an Egyptian mirage on a hot summer day.

I no longer think what I cannot touch is real,

Mawkish tongue lost in a mouth of poverty,

I have to bite myself before I’ll heal

— Kelwyn Sole, The Blood of Our Silence.

And bitten myself I have: the language of the colonizer rests easily on my tongue, it dances. It is simultaneously bizarre and a triumph to know that at first my mawkish tongue bent to it, this language, but now it is this mawkish tongue of mine that bends it. English.

This is the nervous condition of the tongue, of the mother tongue, this feeling of triumph and desolation, of gain, and loss. There is a certain desperation to it since my mind has grasped the English language and has held it captive, more than English has held it (my mind) captive. Or maybe both are happening at the same time.

I cannot say the same for my tongue, my tongue is completely colonized, and as Marechera puts it, I too played an active role in this colonization: I took to the English language as a duck takes to water.

4.

MY MOTHER tongue, Setswana, has always been foreign to me. Being a ‘detribalized’ African born and bred in the township, there was already the first-hand experience of alienation from the rural Setswana of ‘my people’, that is, my father’s people. I remember when on school holidays we visited some of our family who lived in the Free State, there was often lingual confusion between the township children and the children of the rural areas. We were teased for the way we spoke and we teased them in return for the way they spoke. A game of jealous children, each group jealous of what the other had.

The township tongue has no loyalty since the township is a hub of patois converging in a place of no space. Language is a thing that happens in the same way that sexual exchanges take place. I am able to merge isiZulu, Sesotho, and English in the same sentence. The ghetto language of Tsotsitaal, a language game of a much older generation, is a perfect example of the township lingual trajectory.

I don’t know what can I do with myself.

— Thembi Seete.

The post-colony has bred an effervescent gathering: the dream-making machine that is my generation. We inhabit dreams more than we smoke marijuana, actually. We tease white people. We dress cool. We want. This is bold, and it is beautiful, yet, there is also the many-headed Medusa that is our sheep mentality. One does, we all do. Writing in our own languages is cool, again. The bubble-gum factory of the ‘90s is ebbing from the consciousness of the black poet.

We want Biko back! We want our languages back!

Wait.

I will confess, for the purposes of revolution, and tell you: I do not know where to find mine.

Enmeshed by the literature and the aspiration, I have no actual location as to where I could find it.

Help! I too want my mother’s tongue back.

It appears to me now that to write is also to specify location since writing, in its various forms, can replace a dotted map—dismissing the laws of visual cartography and replacing them with the mental flag-posts of delirium. So it is noticeable (in my case at least) that language, the tongue, madness, and writing, are not wholly separate; hence it is imperative then to imagine what it is to be a black (female) millennial who writes and happens to be African simultaneously.

For the African writer writing under the guise of the nation state, or even trying to write independently of the nation state, writing is not only tedious, it is also the aftermath of a completely personal perplexity and internal turmoil. It starts slowly, like the unravelling of a prophecy, and ends with the shattered amphora that is identity. And then comes the angst, the small jealousies concerning those who write better and those who do not, in and outside of the nation, yet always, something remains the same for all writers: writing involves a dramatic amount of sitting down and facing the blank screen, or even the naked page for the embryonic black poet.

This writing thing is the Borgesian labyrinthine forest where Narcissus (whose reflective faculties habitually rely on mirrors) walks blindfolded in the naive attempt to emulate—and brood continuously—on the inner self; self that is easily saturated with the vanity and self-consumption of the society at large. Playwright, dramatist, poet, I plead that you reminisce on the simplicity of the business of writing: it is deeply personal. Also bear in mind the ill-fated misfortunates of the writer: his/her lot commences when he/she assumes to be his/her audience’s marionette.

Fellow Kafkanian, whether you even have an audience is highly questionable!

At all times, remember Papa Achebe and the Igbo proverb he recollects: Where something stands, something else stands beside it.

5.

I IMAGINE that Mother God stands silently before Mother Tongue; that her love is the deep valve of incoherence and the beginning of all that ends. Like a sentence. When I cannot breathe a word onto page, I will think of Mother Tongue as Mother God—of the tongue as a silent deity, and the word as the blood red and not-so-clean God. In any language she is not clean. I imagine that Mother God is the one who demeans colour and remakes it in the face of all that we have scorned of her, of human expression. She is the one who hides behind the patriarchal notions of language, of writing, of our tongues, our minds, and then shames us for believing in them.

When I write I imagine the sacred womb that is my mother’s and how it allowed me to rest in the placenta of her hurt, and then live to describe the experience in words that supposedly do not belong to me.

I write what I like.

— Steve Biko.

So tell Mother Tongue that Mother God has just salvaged her own salvation from the rancid spawn of a world with a million faces.

Tell her I know now, tongue to pen, that all the secrets rest under the tongue.

DOWNLOAD: Selves: An Afro Anthology of Creative Nonfiction

About the Author:

MAPULE MOHULATSI is a reader and writer. Her work has been published in Enkare Review, Itch Magazine, and This Is Africa, amongst others.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions