The Miles Morland Foundation held its second annual Creative Writing Workshop in February. A group of writers who had applied to the Miles Morland Writing Scholarships were invited for ten days of learning, reading, writing, and conversations about how to improve their skills. The Workshop, which was held on Bulago Island, Uganda, had two phases: Fiction classes facilitated by Giles Foden, author of The Last King of Scotland and creative writing professor at the University of East Anglia; and Nonfiction classes led by Michela Wrong, renowned journalist and author of such required readings as In the Footsteps of Mr Kurtz and It’s Our Turn to Eat: The Story of a Kenyan Whistleblower.

Brittle Paper asked the participants—Lillian Akampurira Aujo, Wairimu Murithii, Tsholofelo Wesi, Nkiacha Atemnkeng, Sandisile Tshuma, Otosirieze Obi-Young, Mhla Ncube, and Tamantha Anne Hammerschlag—for comments on their experience at the Workshop.

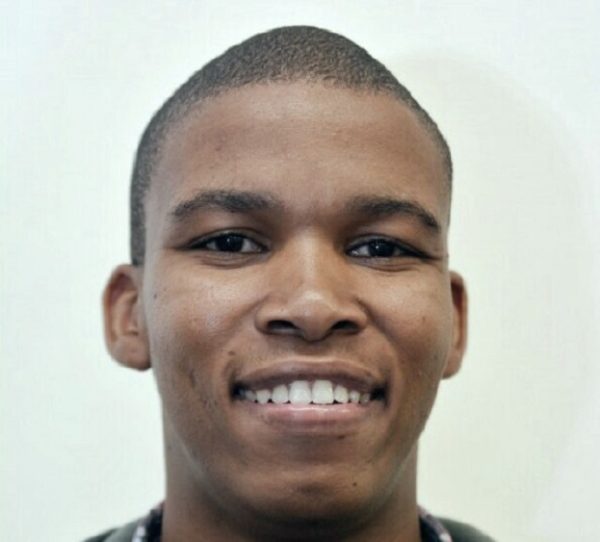

LILLIAN AKAMPURIRA AUJO is a poet and fiction writer based in Kampala, Uganda. She is the winner of the 2015 Jalada Prize for Literature for her story, “Where Pumpkin Leaves Dwell,”and the 2009 Babishai-Niwe Poetry Award for her poem “Soft Tonight.” Her work has been featured online in Prairie Schooner’s “Shoes” issue, The Revelator Magazine, Bakwa Magazine, Sooo Many Stories, the Bahati Books anthology Your Heart Will Skip a Beat, Jalada’s Afrofuture(s) anthology,Jalada05/Transition123, and Omenana. Her work also appears in print in the Caine Prize 2013 Workshop anthology A Memory This Size; the Femrite anthologies Wondering and Wandering of Hearts, Summoning the Rains, andTalking Tales; and in the Babishai-Niwe publication A Thousand Voices Rising. She has been a mentor in the WritivismAt5 Online Mentoring program. She is a 2017 Fellow of the Ebedi Residency in Iseyin, Nigeria.

I liked the format of the workshop; going through each person’s work and getting to hear what everyone else thought of it. With me, there is always the thought that I missed something pertinent to the story—especially since the stories were diverse in genre, theme and setting—and maybe that is why in some cases the story may not speak to me. But here we were in a group of ten, all of us privy to the inner workings of the writer’s mind at the time they wrote the story. I should make it clear that we discussed the story before the author could say anything; so our opinions were unsullied by the author, so to speak. And then you have the opportunity to compare original ideas with execution.

In the afternoons we discussed elements of writing. I know, it sounds simple, yet any writer will tell you not to be deceived or daunted; I mean, this is why one’s writing works or fails. Before the workshop there were things I did out of instinct, there were things I had no name for. But here I was seeing these devices without my own (skewed) embellishment. As writers we work differently, develop differently; I am the sort of writer that needs to be grounded in the language I am working in. This workshop was a huge reminder of that for me. Of course it is impossible to cover all writing theory in a few days, but the little we managed was enough to see my own writing clearer.

The discussions on creative nonfiction showed me that stories are as near as taking a walk into a village; stories are all around us, we just have to employ the writer’s gaze to see them.

SANDISILE TSHUMA is a Zimbabwean storyteller and public health practitioner based in South Africa. She was shortlisted for the 2016 Morland Writing Scholarship. Her short stories, “Arrested Development” and “The Need,” were published by amaBooks Publishing in anthologies of Zimbabwean short stories. “Arrested Development” won an Honourable Mention for the 2010 Thomas Pringle Award, has been translated into a number of languages, and is included in an anthology, When The Sun Goes Down, which was included as a set book in the Kenyan English language curriculum at secondary school level. A translation of “The Need” appears as “Isidingo” in Siqondephi Manje? Short Stories from Zimbabwe published by amaBooks. Sandisile is interested in questions of vulnerability and resilience in young people, which are the impetus behind her current writing project, Black Girls Guide to the Galaxy, aimed at helping young black women to make the most of the “developmental sweet spot” that is the second decade of life.

His eyes are sometimes grey, and sometimes so dark I can’t tell where the irises end and the pupils begin. The day he says one of the more enigmatic things I’ve heard all year his eyes are blue. Like a Mykonos sky. I think it means he might be in a good mood or there’s a lot of light in the room. I think of how Caucasians’ eye colour morphs, how blood rushes to the surface of their skin when they’re angry or embarrassed and we see their anger or shame before they’ve had a chance to articulate it. Our eyes are brown for the most part and give away nothing. We know where the bodies are buried and we’re not telling. His Mykonos blue eyes twinkle as he describes himself as “a comma at the tail end of the British empire.” Later, I ask Christine, “What did that mean?” “Girl! We should ask Lillian,” she responds. Tammy giggles. “What do you think it means?” smiles Lillian, sage-like and detached. He is about my grandmother’s age. If he is a comma, a pause, indicating that there is more to come then my grandmother is a parenthesis. She is in there somewhere but does anyone care? I am of the born-free generation, the first fruits of post-colonial Africa. What does that mean? On that complicated Island on Lake Victoria I resolve to exercise my hard-won freedom as aggressively as I can. I will write what I like and only that. I remember a lecture by Ngugi wa Thiong’o in Cape Town about the richness of our languages and the power of using them. Maybe I should ditch English while I’m at it? I must find my Ndebele dictionary.

MHLA NCUBE is an actor, writer, philanderer even, director and producer of anthologies, books, plays and films. He was born in Zimbabwe, in the ‘80s. He is a moral relativist who classes himself as a Humanist. In the last two years, he has written a book, made a play, turned it into a film, which just got into this year’s Cannes Film Festival’s short film corner. It’s entitled: the new york Amsterdam news. His latest film: that fly 70s sci fi futuristic shit !! marks his return to feature filmmaking, after his debut: All The Pretty Girls. To date, he has made 2 films and anchored 15 performed plays in London and Berlin. His biggest wish is to find someone who is rich and he swears that he will make them wealthy. Through his work, their future generations will be good. Generational wealth. He writes, directs and produces under the name: Ncube. He acts, under the name: Mhla.

To my surprise, I found myself in the Miles Morland Workshop for African Writers, in February, and gratitude kept me in check. I didn’t mind paying for my flight. They covered everything else. 10 days in Uganda seemed like a dream. The programme was at times scatter-brained, much to its credit. Workshops can get so overwhelming, if they are too rigid. I enjoyed the various conversations that eventuated with the organisers and the hosts. The other writers offered insights that were familiar and alien, all at once. The mix was to my liking. There were some voices one had to lean in to hear, and others that left very little to the imagination.

I wish the programme had been longer, as I hit my stride on the latter parts. I also would have liked an oral history of the Island and its inhabitants. Further to that, room for exploration of taboo themes in a quieter space would have been a plus. However, the level of empathy from the Foundation was incredible. They offered support going forward, and looked at us writers as peers.

The accommodation was ripped from the pages of the travel guide: HIP Hotels, and the food was delicious. When you have so many different personalities under one roof, the chronicled experiences can vary significantly, and each person may declare theirs to be the absolute truth. Who is to say otherwise? My experience will slot in nicely into the highlights package of my life.

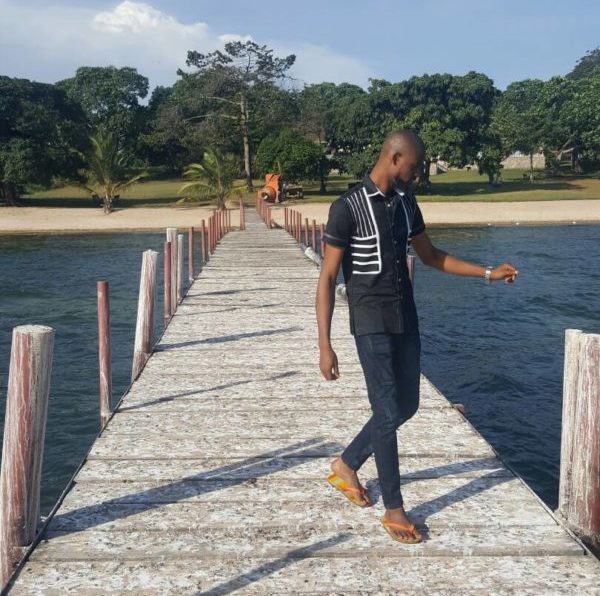

TSHOLOFELO WESI, 25, is a subeditor based in Johannesburg, South Africa. He was born and raised in Taung, North West. His fiction has appeared in Prufrock Magazine. He was shortlisted for the 2017 Morland Writing Scholarship.

Every day, we sat in this homely dining room from which you could see the lake and its distant islands. We walked on this tortuous road from our house, but my laziness would have me think it wasn’t worthwhile for the scenery. It was beautiful.

The experience will add to an existence already weighed down by nostalgia. I still get flashbacks to the sights, sounds and smells of a ghostly paradise, made even ghostlier by the time that’s passed since returning to earthbound Jo’burg.

Now imagine what it’s like when those days are filled with words that attempt to capture something as slippery as experience.

I brought with me a curiosity about writing and storytelling. Giles and the others indulged me in that regard. The writers themselves were uncompromising characters. It was all the more remarkable that the writers exuded love for each other. Just thinking about some of the tender, even heartbreaking, moments overwhelms me.

Fortunately, some of the writing that defined the experience in Bulago has been published on here: Lillian’s haunting poems, which she read to us on one of the nights on the beach, and Christine’s memorable story.

TAMANTHA HAMMERSCHLAG teaches Drama at the University of Kwazulu-Natal, South Africa.

Obi-Young emails me and he asks me to write about Bulago. I don’t know what to write because I did not even know if I enjoyed being on Bulago. I don’t want to tell anyone that:

It was long, intense, full of theory.

It was a strange quasi-colonial.

Fraught with beauty, politics, poverty.

I loved it for the people. The other writers. The generosity of being. The affirmation. The feedback.

I caught a boat which I had never done before in my life.

I was terrified.

Exhilarated.

I ate avocados fat and full of flavour and I tasted the soil in their flesh—and I felt in love.

At night, I sat under a mosquito net and typed a WhatsApp message to a man who was scared to go to work the next day.

I sent him a string of avocado icons.

Rich in love.

Full of flavour.

And then, when he didn’t write back, nor answer the phone when I returned, I saw myself for what I am—a character—I am nothing more than a character in one of Obi-Young’s stories.

And I missed Bulago.

The intensity.

The strangeness.

The spider webs.

The people.

OTOSIRIEZE OBI-YOUNG is Deputy Editor of Brittle Paper. He has completed a short story collection, You Sing of a Longing, and is working on a novel.

The evenings were the most beautiful. The first time we watched the sunset, on the hotelier Ali’s sister’s invitation, it was breathtaking, the sun on those flowers, its electric on the calm lake. We stood there, glasses of wine in hands, in two groups, mine talking about Giles Foden’s novel-in-progress.

The classes were interesting: there was theory, followed by Giles’ invitation of comments on how we had engaged the technique in question in our writing. We’d each come with photocopies of select pieces of our writing, short stories or excerpts, and of synopses of any fiction or nonfiction projects we had in mind. We read these, three per day, returned with comments for discussion. Interestingly, surprisingly, the man Miles Morland sat through our classes, making comments like the rest of us. For three days, we discussed fiction. Then after Michela Wrong facilitated the nonfiction session, with a helpful list of books, we set out for the village, to talk to the villagers, to look for stories. Michela and Mathilda Edwards were concerned about our comfort, frequently asking what we liked or would prefer.

I liked the diversity of our group. Lillian. Wairimu. Nkiacha whom I’d known for years. Mhla Ncube whose name I set aside two nights to learn. Tsholofelo. Tammy. Christine. Sandisile. We were a lively, lovely congregation of ideas. And might have been more had our arrival not been preceded by sad, stilling news: Joel Nevender, meant to be with us, had passed on.

One night, we danced on the beach. One afternoon, we climbed the highest peak on the island and had lunch and read brief pieces and ended with a fiercely political conversation. The afternoon Miles left, Nkiacha and I were driven to our hotel apartment with the same boat. I’d alighted on the quay, was saying goodbye, and then I said to the driver to wait. I reentered the boat and hugged him.

WAIRIMũ MũRĩITHI is a full-time reader, sometimes-editor, sometimes-writer and sometimes-MA-student in the University of Pretoria’s English Department. She lives, loves and cycles across Johannesburg, and sends messages and memories [home] to Nairobi. She has a thing for green coats. When she is not doing all the things mentioned above, she is asleep. If you feel like it, you can find her writing and curatorial work in Afreada, Ja. Magazine, Kalahari Review,Short Story Day Africa, Emergence, This is Africa and The New Inquiryand her blog, ku(to)zurura. Few things make her happier than potatoes.

If ever there was a time I needed reminding that writing is as much a lifesaver as it has been a drainer of life, it was the week I spent on Bulago in February 2018. When you are compelled to drop all the things you’ve been doing to avoid writing, and actually pay attention to the writing . . . it’s an unsettling experience, and artists often need to be unsettled anew.

What stuck with me the most—perhaps because of the windy, spidery, neocolonial feel of the place—was how important it was for me to find what I know, or what I could know, in the midst of so many unknowns. So much of my writing has come from an urgent need to know more with little consideration to the possibility that I already have so much to unpack for myself. It’s why I’m having the hardest time writing the 1,000 words about my body that I started on the island. And it’s only after I recounted my experiences to a friend, afterwards, that she reminded me of a similar story Chimamanda Adichie wrote: “Jumping Monkey Hill.” Rereading it, and perhaps I projected, I’m glad I know Ujunwa a bit differently now.

NKIACHA ATEMNKENG is a Cameroonian writer who works at the Douala International Airport. His works have been published in the 2015 Caine Prize anthology, The Africa Report, This Is Africa, Bakwa magazine and Brittle Paper. He attended the 2015 Caine Prize Writers’ Workshop in Ghana and the 2017 Nigeria-Cameroon Literary Exchange Project. He is a Sylt Foundation Writing Residency Prize winner and an Ethiopian Airlines Cameroon’s 2016 Blogging Award winner. He tweets from @nkiacha.

Every time I think of Bulago the first thing that comes to mind is its legion of lake flies and spooky spiders, which produce blankets of cobwebs all over the place. Bulago should be renamed Spider Island. I was amazed by its natural beauty, the plethora of birds and the otters.

I’m working on a fresh thing in African Lit, aviation fiction, a novel set at the Douala International Airport in Cameroon and on board planes flying in the sky. I needed a little feedback on my writing arc, so when the MMF workshop invitation appeared in my inbox, I decided to fly to Uganda. An excerpt of the rough first draft was constructively critiqued. I heard many thoughts and suggestions about writing the book from Giles, Michela, and the other writers, some of which I will make use of. The facilitators also gave me a list of airport novels published in the West which I had never heard about, to read and see how other writers approached the books. Hope they don’t influence my story a lot.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions