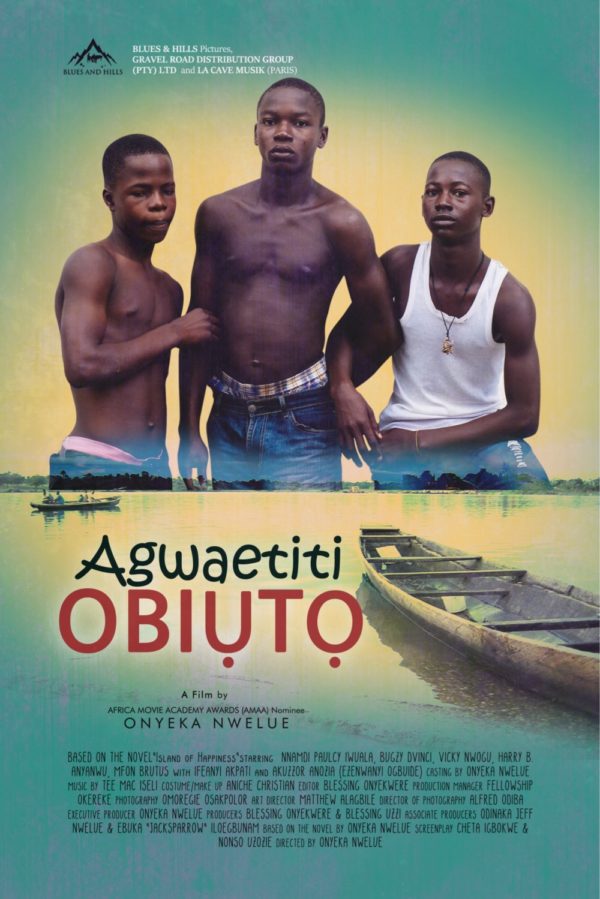

As the Africa Film Trinidad & Tobago opens tomorrow, my first fictional Igbo Language feature film, Agwaetiti Obiuto, will screen on 24 July in Port of Spain. I was there last year where my documentary film, The House of Nwapa, which was nominated in the Best Documentary Category of the 2017 Africa Movie Academy Awards (AMAA), was screened, and during the Q&A, I promised them I would return to the island with a new film. That is what I am doing now. A promise kept.

But there is one person who remains my biggest inspiration in filmmaking, even as this new film has been compared to the works of Spike Lee (by Toyin Akinosho), Luc Godard (by Chigozie Obioma) and Ousmane Sembene (by Sikhumbuzo Mngadi). I am humbled by these comparisons, but it is the Nigerian film director Kunle Afolayan who has been my greatest inspiration in filmmaking.

As a young man struggling with the dream of telling stories, I saw Kunle’s Irapada, but the film that stole my heart was his The Figurine. I became slightly obsessed with Kunle Afolayan. If he knew how obsessed I was with him and his work, he didn’t show it. He was very accommodating and charismatic with me when I began to find excuses to be around him. I reached out to him and he was what I thought he was: a great guy.

I attended the Africa Movie Academy Awards (AMAA) in Yenagoa where The Figurine won several categories, and the intensity of my obsession, admiration and respect grew. I began to see myself as Kunle Afolayan. This made me stay on the set of Phone Swap for hours despite being diagnosed of Ectopic Kidney—with a swollen face and swollen legs, with all the weaknesses, I kept following Kunle and his success. I wanted to be successful.

Kunle’s success became infectious and I began wanting to achieve that dream: make a film. I had the script for The Distant Light. I was able to convince a benefactor who then bought flight tickets for a film crew from The Netherlands who came to Nigeria to film with me. I took them to pay a visit to Kunle. He encouraged me and told me that nothing was impossible, but he was also realistic: there were better cinematographers in Nigeria I could have contracted with. “That money used in flying them could have been used to get things going,” he said. I was young; it didn’t make sense to me. I thought the More White or More European, the Better. I was a fool. I took my crew from Lagos to Oguta and the project failed. The folks went back to Europe and we severed our relationship. They needed to do storyboards but instead they drank a lot of beer and one of them ate kolanuts and ended up in the hospital. We spent two weeks doing nothing. Money burnt. A dream waned. I slumped into depression for months.

That year, I was persistent enough and I got admission to study Film Directing at Prague Film School in the Czech Republic. Someone was behind it. While there, I made my first short film, The Beginning of Everything Colourful. It was shot in Paris and starred British actor and model, Dudley O’Shaughnessy, who is famous for appearing in Rihanna’s “We Found Love” video, who I would later invite to Nigeria. I began to think of myself as a filmmaker.

Kunle Afolayan’s energy is infectious. For many people, he is not easy to love. I understand why. We are easily threatened by people with lots of guts and people who do things differently. Personally, there is nothing I want from Mr. Afolayan with this piece. I would have written to praise Tunde Kelani, the man I consider the Father of Modern Nigerian Cinema, but there are qualities that Mr. Afolayan possesses that no filmmaker in Nigeria does. Mr. Afolayan is creative and also business-savvy. He understands the aesthetics of filmmaking and, in a country like Nigeria where creativity does not bring in money, he has been able to build a legion of business networks, making filmmaking look glamorous and alluring. Strangely, when I didn’t win at the AMAAs and had rushed to greet him, he said something: “Make a better film.”

The last time I saw Mr. Afolayan was in Paris, while I was on transit to Boston. I was confined in a wheelchair at the airport and he was flying to Los Angeles with other Nollywood greats like Dakore Egbuson. He came over to me, tapped me on the head, and said: “You’re always sick.” And we laughed.

If Mr. Afolayan understood that my admiration for him stemmed from his hardwork, then he must know that he has inspired generations. People have complained about the quality of his storytelling in his recent films, but has he promoted them well? He did. Did we watch them? We did. So he has achieved two things:

1) Got us to watch the films.

2) Discuss them.

Let’s talk about October 1, which he humbly asked me to read its screenplay before it was shot. After the film was made, I reviewed it, and people have said how I was ass-kissing. You don’t kiss the ass of Kunle Afolayan. It does not pay. He does not pander to people’s sensibility. I wouldn’t want to talk about the effect the marketing of another of his films, The CEO, had on me. I haven’t dedicated Agwaetiti Obiuto to Kunle Afolayan, but I am writing this to say how much he has inspired me.

I am also happy to mention how Ishaya Bako has been a backbone and a huge inspiration to my budding career as a filmmaker. Ishaya saw an Igbo Language film without subtitles! Who takes such pain? And he made delicate notes that shaped my narrative. The film I see now gladdens my heart. It can never be perfect, but what I went out to achieve was achieved.

I will continue to admire and respect Kunle Afolayan for being a huge inspiration to me. I am unable to write this when he dies because I may not be alive. So here is my tribute to say how much I love and respect him, to read by him while still alive.

Chineke gozie gi!

ABOUT THE WRITER:

ONYEKA NWELUE is an award-winning writer, filmmaker, and educator. He is a Research Fellow at Center for International Studies at Ohio University. His fictional Igbo Language feature film, Agwaetiti Obiuto, screens at the 2018 Africa Film Trinidad & Tobago on 24 July.

Why Matigari is Adapted into a Film but not any other Book by Ngugi ⋆ JeJeLee January 03, 2019 10:04

[…] in Kigali, Rwanda that Ngugi’s novel Matigari is being adapted to a film by Nollywood director Kunle Afolayan. The adaptation will be done as a collaboration and a co-production with the South African as well […]