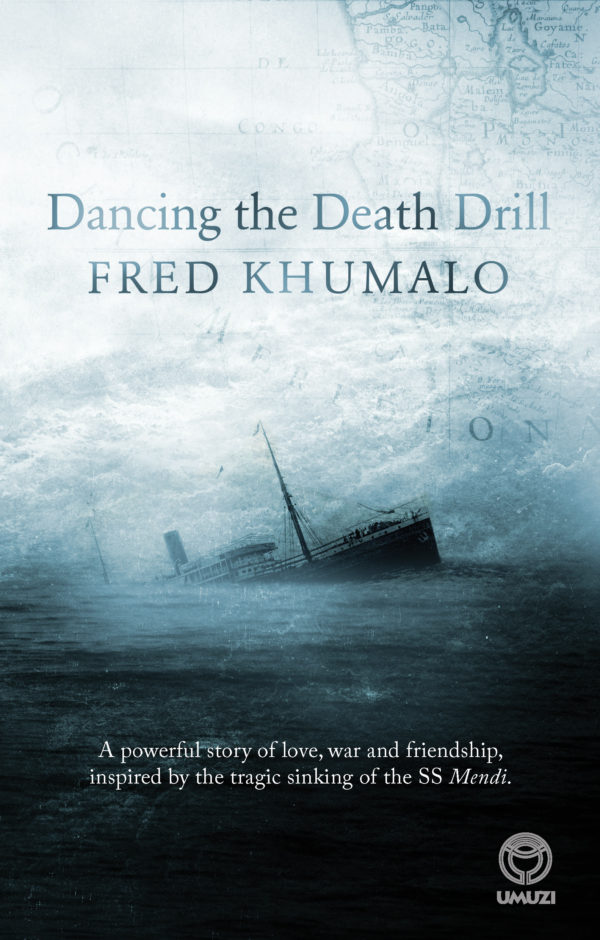

Fred Khumalo’s 2017 novel Dancing The Death Drill is based on the sinking World War I warship, the SS Mendi. Tasked with transporting black South Africans to the Western Front during the War, the SS Mendi, on 21 February 1917, collided with a mail ship, the SS Darro, leading to more than six hundred people drowning in the English Channel. Khumalo’s revisitation of this incident is part of a growing conversation on the resurgence of historical fiction, and why more and more contemporary novelists are embracing the genre.

In recent piece for The Johannesburg Review of Books, Khumalo—whose other books include Bitches’ Brew, which won the 2006 European Union Literary Award; Seven Steps to Heaven; Touch My Blood; and #ZuptasMustFall—reflects on the use of historical fiction for activism.

Read selected excerpts below.

RECENTLY, I found myself in a part of Gauteng, South Africa that I hardly ever visit—the West Rand town of Roodepoort, just outside the ring of highways that enclose Johannesburg.

I was there to address a vibrant and interesting book club whose membership comprises retired professionals—predominantly women, Afrikaans and white (though people from other groups are welcome).

What struck me about members of the Quellerie Leeskring was the passion they have for historical fiction. Which, I suppose, is why they’d invited me to talk about my novel Dancing the Death Drill, which is based on the sinking of the troopship SS Mendi. The Mendi was charged with transporting black South Africans to the Western Front during World War I, and on 21 February 1917 more than six hundred drowned in the English Channel when it collided with the mail ship SS Darro.

In my casual interactions with members of the club, both before and after my presentation, I picked up references to other texts they’d read recently, which left me in no doubt that their preference was for books that explore history in new and reflective ways—as I hope mine does.

The Quellerie outing reminded me of another recent presentation of mine, this time to the Literary Alliance, a Johannesburg-based book club that is predominantly female and exclusively black. It is also very young: everyone there was younger than fifty. Again, in my interactions with the members of this club I noticed the titles of many historical novels, by both local and international authors, being bandied about.

I want to suggest that the historical novel, once the preserve of cosseted heroines and doughty heroes, warlike hordes pouring across bleak landscapes on foot or settlers making grim progress in small groups of ox wagons, is back in favour—but it is dressed in new clothes.

It comes, these days, with attitude and a breathless literary intensity; a fire in its belly. From the violent Wolf Hall by Hilary Mantel to the revelatory The Spiral House by our own Claire Robertson; from the left-field and quirky Days Without End by Sebastian Barry to Zakes Mda‘s feisty Little Suns, historical novels are winning favour with the reading public, and winning important literary prizes.

…

My own novel Dancing the Death Drill, though inspired by historical events, does not pretend to be a straightforward historical text. I use the Mendi to launch a conversation around pockets of history in South Africa, West Africa and indeed Europe that have been hidden in the past, in the name of political expediency.

As a novelist, I am concerned with the ways in which communities transform their historical experience into the symbolic terms of myth, and then use mythologised narratives of the past to organise their responses to real-world, present-day crises and events. As a genre, historical fiction can be a powerful tool in the hands of a writer who is also an activist, which I count myself to be. The writer–activist can, by weaving a fictional story around a factual but little-known historical event, such as the sinking of the SS Mendi, insert chunks of what might be called ‘hidden history’ into the public domain. This is, of course, exactly what I sought to do in Dancing the Death Drill. But, in addition to that, I wanted to use the novel as a springboard from which to launch an enquiry into a trio of quintessentially South African themes: race, identity, memory, and their intersection with the ‘land question’.

When black men decided to go and fight in Europe, they did so in the belief—the mistaken belief, as it turned out—that if they supported the British Crown in the war, the Crown might consider rescinding the Native Land Act of 1913. Under this law, eighty-seven per cent of South African land had been given over to white people, who were and continue to be the minority in the country. The majority, the black people, were forcefully removed from their ancestral land and driven to reserves where they could not pursue farming and ranching, which before then had been the mainstay of black life. Having lost their land, they could also no longer raise cattle, a practice central to their culture through centuries on the southern tip of the continent.

When these men went to war, they were desperate. They were on their knees, so to speak. Their desperation made them susceptible to abuse. They were eager to do anything to ameliorate their plight. Needless to say, all the promises that were made to them were never fulfilled.

My job as a novelist is to record what happened back then, but to also raise a flag, to caution that the country still has some unfinished business. If we don’t resolve the issue of land redistribution decisively, and in a manner that takes full cognisance of the extent to which the majority was robbed, it may come to haunt us. It happened to our neighbour, Zimbabwe.

Historical novels show us how the origins of many present-day problems lie in the past; they are vehicles for the necessary journeys that nations must take to be healed; they help us reimagine ourselves in the present day.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions