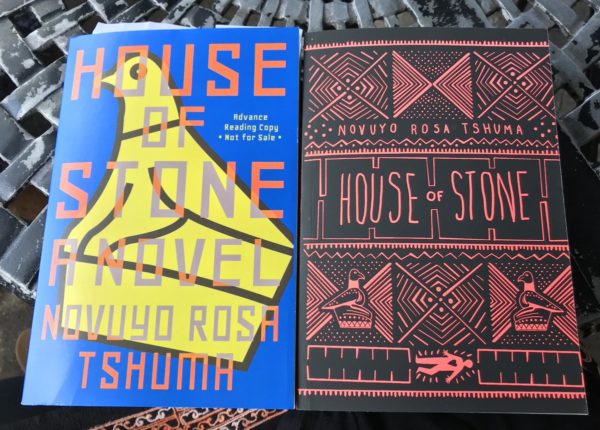

Novuyo Rosa Tshuma’s novel House of Stone, an exploration of family history, colonial Rhodesia, and the birth of modern Zimbabwe, was released in June, in the UK by Atlantic Books, and in South Africa by Penguin, and is forthcoming in the US from W. W. Norton in January, 2019.

The novel, which comes with blurbs from NoViolet Bulawayo (“Tshuma writes in an arresting and trenchant prose that shows a gifted artist at work”) and What Belongs to You author Garth Greenwell (“Novuyo Tshuma writes with an equal commitment to Joycean formal inventiveness and political conscience, and the result is absolutely thrilling”), was praised in a review in The Guardian by Helon Habila.

Here is an excerpt from the novel, published in The Johannesburg Review of Books.

Book One

Of Fathers and Grandfathers

A man of consciousness, gifted with a mind and a blank screen and a keyboard such as I have, makes his own hi-story proper. There is no better way of gaining possession of yourself than chewing the bones of the mind over the question, Who am I?And who you are starts with a robust family lineage in which to cultivate your roots. A man has to be able to trace the details of his family hi-story at least two lineages down, to his grandfather. Otherwise, he can’t really claim to be standing on solid ground. You have to be able to point to a man and say, ‘That’s my grandfather.’ Or make do with a sepia-tinted photo, at least, chewed at the edges by the affectionate teeth of time.

As my surrogate father has neither glossy photo nor the confidence to point and say, ‘That’s my grandfather,’ I have been left with the task of resolving the matter of our family lineage. And it hasn’t been easy, this. For, one moment, while ensconced in the toasty Bell’s, Abednego claims that his father was the man he grew up calling ‘Baba’, husband to my surrogate grandma, that treacherously demure woman who was in her heyday such a blot-out-sun, so blinding was her beauty. And then, the next moment, having become much too heated from the Scotch whisky, he makes rather dubious assertions that his real father is a certain James Thornton, once-upon-a-time owner of that Thornton Farm whose lush harvests salivated many a tongue in the adjoining Tribal Trust Lands where young Abednego grew up, relegated to live there by the state during the time of racial segregation, back when Zimbabwe was still Rhodesia.

When he blubbered this in my lodgings two days ago, I wrinkled my nose and raised an eyebrow. Frowning, he pulled up his shirt sleeve and thrust his arm in my face, prodding the flesh. His inner forearm, which doesn’t get much sun, is closer to cream than yellow, and the hairs are a pale gold rather than a deep brown.

As though sensing still my scepticism, he launched into a dramatic monologue of the day the farmer attempted to lay claim to what, by blood and sperm, was allegedly his. Baba was sitting outside his hut in the shade of the mopane tree on the morning in question, cleaning his FAL rifle and decked in his full Rhodesian African Rifles army apparel—a bush-green shirt tucked into pleated shorts, woollen hose tops, black stick boots and a slouch hat—busy bobbing his head solemnly to my (surrogate) Uncle Zacchaeus as he read verses from the bible, in an English that the old man understood and extolled but did not himself know how to read, when Farmer Thornton came wheezing over the hill of the north-east, from the direction of his farm, telephone cord in trembling hand, dust simmering about his sandalled feet. My surrogate father Abednego, who had been crouching behind the kraals some hundred paces from the mopane tree, listening to Zacchaeus read and trying rather unsuccessfully to mimic his brother’s fanciful pronunciations, straightened up and gawked at the farmer.

‘Give me the boy!’ cried Farmer Thornton, gesticulating towards Abednego and lambasting Baba for not looking after him right, for sending the little munt Zacchaeus to school and not my surrogate father.

My surrogate father began to squirm, his yellow face ripening at the farmer’s outburst. He’d never thought, in all his nineteen years, that he could go to school. Zacchaeus was the special one, the younger son and yet the cimbi of Baba’s heart, and although something bilic used to brew inside him during those first days when he would watch his younger brother being shaken awake every morning to go to the sole school for Africans in the district some thirteen kilometres away, this bile had since settled in its rightful place in his gallbladder.

The farmer’s outburst made him feel all funny inside. He knew and had always taken secret delight in the fact that the farmer had always had a thing for him. Everybody knew, Baba, mama and even Zacchaeus whose buttocks the farmer always thrashed with a telephone cord whenever he caught them stealing crops in his fields. But this impassioned outburst, now, that was another thing altogether, bound to find the ears of the wind and be carried for an entire jealous village to hear. And so he squirmed, my surrogate father, and scowled and made all sorts of ugly faces, all the while secretly savouring the farmer’s words.

Baba raised his rifle until it was trained on Farmer Thornton. ‘Get away from here, mani, you fucking civvy!’

Continue reading on The Johannesburg Review of Books.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions