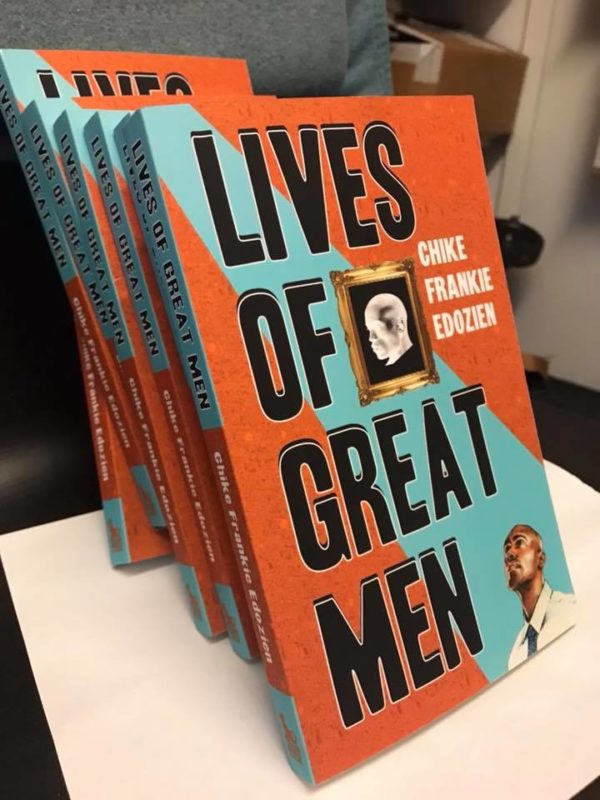

WE ARE MORE THAN TRAGEDY: A REVIEW OF CHIKE FRANKIE EDOZIEN’S LIVES OF GREAT MEN

To read on the news about queerness in Africa is to read about secrecy, mob assault, imprisonment, asylum, homelessness, death. In Chike Frankie Edozien’s LAMBDA Award-winning memoir Lives of Great Men: Living and Loving as an African Gay Man, there is the awareness of all these, but more awareness about love and hope and life; about humans loving other humans and learning to make homes out of each other; about people loving so defiantly that that very simple act of love becomes worthy of celebration. In this luminous book, we are exposed to a universe of important but untold stories: the queer African is brought out of the shade of society’s bigotry and thrust into the light. They are given the starring role, finally, and presented to the audience in full view of their humanity.

There’s Scott, “the good doctor,” his loveable boyfriend. He is the sunny, walking burst of light. Through the writer’s adoring eyes, we appreciate this beautiful Japanese-American man eager to embrace his lover’s culture, a remarkable man who dedicates his career to providing medical care for the homeless. Young Kwabena is another unforgettable character from the book. A lifelong resident of Accra, he is a successful businessman with transactions cutting across Accra and Cape Coast. A jovial, virile man, he easily passes for heterosexual, and despite familial pressure, he is determined to remain true to his chosen life. He is the kind of person you want to have a drink with. Blame it on Edozien’s intimate descriptions. On the other hand is Ekow, the old lover our narrator has no fond memories of. From playing the “drain-the-foreign-boyfriend” card to ignoring him completely while they are at lunch with his mother, such outrageous behaviour is what makes him striking.

We get to learn deeply about Edozien through his relationship with these varied men and women—even though the book is heavily invested in their stories, the most resonant parts are those which focus primarily on his own journey. In one particularly jarring passage, his father prays loudly, during a family gathering, for God to change the minds of closeted homosexuals, knowing fully of his son’s sexuality. While many grown men would cower at this and retreat into their shell, Edozien is instead propelled by the same audacity which makes this book possible: He confronts his father afterwards and makes it clear that he will not allow himself to be shamed. The wording here is a standout:

Without allowing him to speak I make it clear that I am in no closet. I am proud of who I am. I don’t need forgiveness. I don’t need to change.

This is a message not always preached: the pure, unconditional validity of queer women and men. With religious bias and ignorance continually equating their existence with mortal sin, this is especially important.

A self-made man, Edozien survives the early hustle-and-bustle of immigrant life by working different jobs including as a janitor and telephone operator. He eventually launches a journalism career, working with the prestigious New York Post.

Despite its thesis of successful gay men leaving the continent because of their sexuality, Lives of Great Men narrowly escapes possible criticism as a book written from the highbrow perspective of an upper-middle-class Nigerian fortunate enough to live abroad, and far from the real day-to-day disasters of being a gay man in Africa. While such a concern is subverted by Edozien’s repeated acknowledgement of his privilege, it would be rather ostentatious to push it in the first place. First, to insist that Edozien’s account is not valid because of his privilege is to pretend that the story of queerness can only be told from the viewpoint of gloom and doom. And that those who are fortunate enough to avoid most of the tragedy are somehow not authentically part of the narrative, an idea which is self-defeating by virtue of its ridiculous logic. Secondly, the narrative is not conceited enough to focus merely on the writer’s personal, first-hand experiences. It is a painstakingly journalistic account of the predicament of ordinary queer men and women in Africa and in the diaspora. A book that makes room for everyone.

Or at least it makes room for a lot of people. Lives of Great Men sometimes shifts away from sexuality to touch upon the broader subject of minority relations. There is the gruesome murder of Amadou Diallo in 1999, devotedly covered by the then younger Edozien. Another hidden figure, the unarmed, Guinean immigrant was shot 19 times by the American police. With its extent of focus, Diallo’s story is a reminder that, when backed by the state, hate can be even more venomous. Which, of course, is the case of queer lives in most African countries—the institutionalization of populist hatred founded on religious and pseudo-cultural sentiment.

An important point Edozien makes is that the inhumane treatment of those considered different in Africa has terrible consequences for the continent itself. Instead of embracing all its peoples in their varying shades, the continent chases its children out just because of who they love. And that is the sad story: a shameful loss of valuable human resources to the West just because we cannot get over our senseless bigotry.

In tales like this, there is often a wretched romanticisation of pain and trauma. It is almost as though they peddle the unsettling idea that there is unexpected healing in being broken, that there can be no beauty without being bruised. Thankfully, Lives of Great Men does not transact with such cheap emotional currency. Being broken is being broken. There is no glorifying it. What the book stresses, however, is that tragedy is not the only complexion of queer lives, that they can be full of colour and music and laughter, too. You can almost hear, from every page: We are more than tragedy. We are so much more than the darkness we face.

But as one reads on, a problem seems to plague the book. While the individual stories in the book themselves do not sanitize the characters, the underlying subtext seems to imply that these characters, by the fact of their systemic oppression, have been morally elevated to the status of martyrs—saintly men of pure greatness. That would, indeed, be lavish. What becomes clearer, upon further reading, is that Edozien’s label of greatness on the lives of the queer men in focus is more prescriptive than it is descriptive. Writing is political. Writing, for George Orwell, indicates a “desire to push the world in a certain direction.” And this is what Edozien attempts here. He proposes that queer Africans do not need to see themselves as the defeated or the unwanted. They can choose their own modifiers. The label of greatness is a normative counter to society’s linguistic dehumanization of queer lives. Why be tragic when you can be beautiful and wondrous and loud and [insert chosen adjective]?

In the end, what ultimately counts is doing justice to the men and women in these stories. And in that regard, Edozien’s memoir is a success: a triumphant celebration of difference in a broken world that pushes for the erasure of divergent identities. Everyone deserves to have their existence respected, this book says. Queer men deserve better. Their lives matter.

ABOUT THE WRITER:

Kanyinsola Olorunnisola is a poet, essayist and writer of fiction. He writes from Ibadan, Nigeria. His debut poetry chapbook, In My Country, We Are All Crossdressers, was published by Praxis Magazine. He is the founder of the literary movement, SPRINNG, Society for the Promotion, Revitalization, and Improvement of the New Nigerian Generation. He loves experimental literature, pop culture, and Nigerian jollof rice.

Opinion: Can LGBTQ be Publicly Embraced in Nigeria? - Insight.ng October 08, 2022 23:16

[…] an Author, reported the phenomenon of secret marriages and home partnerships in his memoir, Lives of Great Men. Chike said, “Many Nigerian queers lived together with their partners but couldn’t be […]