Last year, Somali writer and visual artist Diriye Osman, author of the Polaris Award-winning story collection Fairytales for Lost Children and the forthcoming novel We Once Belonged to the Sea, explained the concept of literary androgyny: that gender-straddling sensibility possessed by the best storytellers—women writing men, men writing women. But Aminatta Forna, from the interview she recently gave The Johannesburg Review of Books editor Jennifer Malec at this year’s Open Book Festival, has a different, revealing motivation for writing male characters.

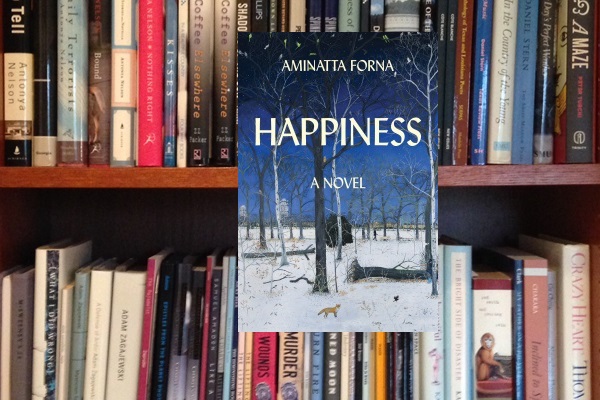

The novelist this year had her fourth novel, Happiness, out. A recipient of the 2014 Windham-Campbell Literature Prize and a finalist for the 2016 Neustadt Award, she is the author of the Samuel Johnson Prize-shortlisted memoir The Devil that Danced on the Water (2002), and of three novels: the Hurston Wright Legacy Award-winning Ancestor Stones (2006), the Orange Prize-shortlisted and Commonwealth Prize-winning The Memory of Love (2010), and the 2014 IMPAC Award-nominated The Hired Man (2013). Presently, she is the Lannan Visiting Chair of Poetics at Georgetown University and Professor of Creative Writing at Bath Spa University.

Read the excerpt from the interview below.

The JRB: In Happiness you write characters from all over the world, America, Ghana, Nigeria, Bosnia. Your previous novel, The Hired Man, is set in a tiny Croatian village. Do you think about the question of authenticity when writing your characters? Or do you think the question of authenticity is overstated?

Aminatta Forna: It doesn’t hold water to me. First of all, we’re talking about something which is an act of imagination anyway, we’re talking about imaginative art. And it’s quite fascinating how the idea of authenticity sticks to novels but not, say, plays, film, poetry, ballet. It seems to have become very much attached to novels but not any other art form. Perhaps it’s because there is one author. But I think that people have to treat novels as an act of the imagination. If what you’re looking for is something called ‘authenticity’—and I feel the same way about the cultural appropriation debate—then stick to non-fiction. That’s got a different deal. If you read The Hired Man, or any of my characters that are not half-Sierra Leonean, half-Scottish, and middle-aged women, and you are unimpressed by them then by all means put the book down. I come to it with the belief that people aren’t that different. That’s what I essentially come to it with. However, people have different experiences. So, for example, in writing male characters what’s interesting is the considerable amount of freedom men have compared to women. The reason I like writing male characters it is that I don’t have to get them home safely at the end of the chapter. Women live extremely constrained lives compared to men, so as characters it’s harder to move them around the page. If you look at Victorian women’s fiction that’s why it was all domestic.

Read the full interview on The Johannesburg Review of Books.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions