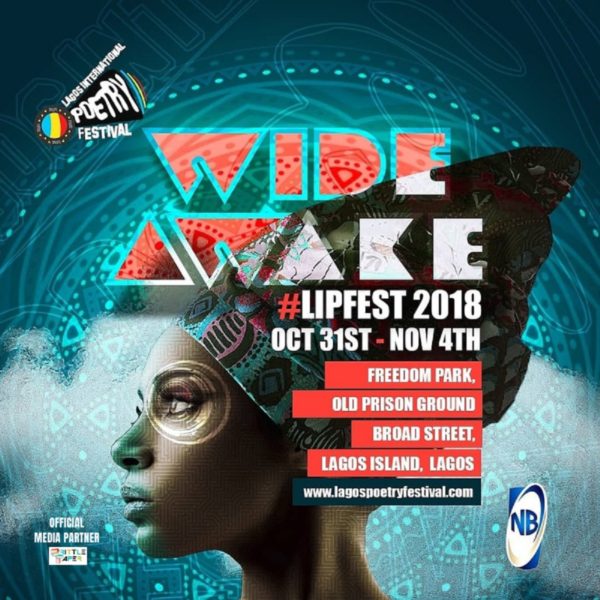

The event corner of the Nigerian literary scene has again gone quiet after our two major literary festivals have come and passed. Aké Arts and Book Festival—in its sixth year—happened only four days before the Lagos International Poetry Festival—in its fourth year—both in Lagos. In the time that these festivals have existed, there has been reasonable progress in the Nigerian literary scene. But with the many reasons to be grateful for these festivals is a personal disillusionment that has grown in me for some time now.

I have attended neither festival, which at first was because I could not afford the expenses, and later because I grew less enthusiastic about them. I especially made a great effort to attend the first edition of LIPFest in 2013, pushed by my excitement to the point of asking people for sponsorship, because I’d somehow seen the festival as something very important in making a life out of writing poetry. One of the persons I’d asked for sponsorship, being sorry that he could not help me, remarked that I didn’t really need festivals to be a good writer. I’d said yes only out of politeness and choiceless resignation. What I didn’t get was this: he was saying that being at the festival would only do as much as watching YouTube videos of writers speaking of the craft or other businesses of writing, the difference being my possible attendance of one or two masterclasses, an opportunity to purchase print copies of some books I’d love to read and getting them signed by their authors. Besides this, the rest may be about writerly camaraderie in which I was likely to find not so much inclusion for myself beyond the position of an observer, even though one might end up going home with—amongst other materials in their festival pack—an established writer’s attention or personal contact. This I’d learnt in three years of following the activities and memoirs of festivals online.

Maybe my opinion of these festivals might not have been modified had the conditions in relation of which I’d thought about them come through. But I’ve been a poet, possibly a mostly dispirited one, whose unpleasure has resulted not from a lack of personal progress but from a rather obsessive passion for community. My initial interest in LIPFest was because I’d naively envisioned an opportunity for young poets to move from the margin to a place of structural improvement. If today that interest has whittled down, it is because I have observed something unlike what I had imagined: literary festivals, in their nature, are primarily for a certain class of writers and other stakeholders in writing. This in itself does not invalidate literary festivals neither is it a faulting of their organizers, but I cannot stop thinking of the upcoming writer and what programs are in place to enhance and encourage them. It is a question of what opportunities there are in relation to the existing talent pool and the structures available to reasonably absorb the flow.

For writers, generally, “upcoming” seems an infinite struggle, and this is especially worse for poets. Aside the issue of how much people appreciate poetry, there is also the matter of bankability. In Nigeria, poetry isn’t as marketable as prose; I cannot tell if there are any major publishing houses in Nigeria actively engaged in poetry as they are in prose. I suppose that, aside art, they also have to look at business—even as I am not sure of the point, sentimentally speaking. Despite this imbalance, we all can speak of progress for Nigerian poetry lately. But we can still ask how much of this progress is homegrown. Mention Praxis Magazine’s chapbook series, efforts by Expound and Brittle Paper, Poets in Nigeria’s Nigerian Students’ Poetry Prize and the Ebedi Writers’ Residency, and those become the notable much that we can say of poetry in Nigeria. This means that the upcoming Nigerian poet is alternatively bound to pitching validation and facility internationally in terms of poetry prizes, degree-awarding institutions, publication presses, media platforms, fellowships, workshops and residencies. We can say that Nigerian poets are maximally talented, but can we say the same of domestic nurturing and support?

Generally, festivals are exclusive, and in Nigeria they easily become pretentious and inattentive to people at the lower levels. For a very consistent reason, it is only a particular circle of people who will be invited and can afford to be part of a literary festival. The other, larger number of people is simply left out, which doesn’t seem to me the best practice. Our literary community needs way more than that: because LIPFest cannot engage with the young writer more than it is doing, there is definitely the need for a more inclusive (or an exclusive) program for the upcoming writer. In Nigeria, poets need structures with foundational intent, with initiatives like workshops, fellowships, and residencies—not to the exclusion of festivals but more than simply festivals. I suppose that those who are established owe it to the community to remember their initial struggle, the slim options they went through, to remember that there are still others upcoming and caught in such conditions.

Having a masterclass as an activity in a festival does very little; establishing it independently, as a recurrent event with a specified vision, and tracking the progress of the various people it engages with does more. When one thinks of the masterclasses that happen during LIPFest or other occasional poetry masterclasses, the brevity and inconsistency become strong limitations of what could otherwise be achieved. Compare such masterclasses to, say, the Purple Hibiscus Creative Writing Workshop, and the difference becomes even clearer. We need programs capable of going out of their way to seek out nascent talents, to sponsor and nurture these talents. We need resource institutions for writers who need creative spaces to produce works, spaces that will do more than the Ebedi Writers’ Residency with its mysterious processes. We need to create agency for that broke poet who needs a lift to build their art, agencies that would be better managed than the doubtful NLNG Prize for Literature’s poetry editions.

The institutions we already have are very far away from those at the margins: LIPFest and Ake Festival are examples of such institutions. We are done with the excitement this time, winter is already here and our wait has begun—until the next episode, when we will all come out in celebration of yet another cult of names.

About the Writer:

Ebenezer Agu is a poet and an essayist. He is editor-in-chief of 20.35 Africa: An Anthology of Contemporary Poetry and poetry editor at 14: Queer Art.

PA December 27, 2018 06:00

Finally, someone mentions Ebedi's mysteriousness. They have no website (or a working one), and nowhere can you find guidelines on how to apply. It's as if you have to be friends of certain people before you can get in.