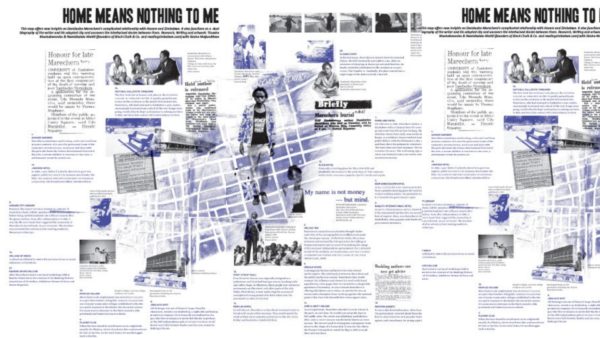

An unusual mapping project has documented the movements of Dambudzo Marechera in Harare. “Home Means Nothing to Me,” published in the June 2018 issue of Chimurenga’s The Chronic titled “The Invention of Zimbabwe,” is the brainchild of three Zimbabwean creatives: Tinashe Mushakavanhu, Nontsikelelo Mutiti, and Simba Mafundikwa.

Their work was shortlisted for the 2018 Brittle Paper Award for Creative Nonfiction, and here is our comment on it:

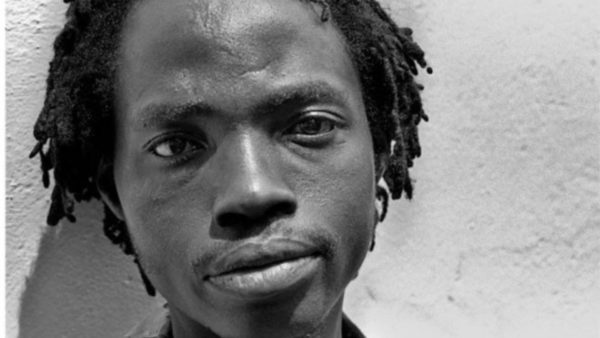

The life and movements of Dambudzo Marechera in Harare, between 1982 and 1987, on his return to Zimbabwe after forced exile in the United Kingdom, are documented in this excitingly innovative mapping project that speaks to the late great writer’s mythology and spirit as well as corrects misconceptions about his work and person.

The project took its title from the film House of Hunger.

But how did it come about—how did they decide that the best way to track the iconic late novelist would be not through conventional literature but through cartography?

“I think the bulk of major scholarship misreads Marechera,” Mushakavanhu writes in his introduction to the project. “Everyone assumes his book House of Hunger to be set in Harare. House of Hunger is actually set in a small town in the east of Zimbabwe. And so primarily the idea of this project was to challenge that sort of popular misreading of Marechera. We wanted to look at him in this place and trace him or follow in his footsteps. It is both faithful and fiction, necessarily because it also plays around with the mythology of Marechera. So we are following Marechera to the places that we know we can encounter him, through his own writing and on readings of the others talking about Marechera.”

Theirs is an effort to locate the man in the loud mythology.

In the map, we tried to let the person lead us to the mythology. That’s how we worked on the project. So the idea was to locate Marechera in actual places. And obviously within that the mythology. For me, the person was in front of the mythology in this particular project. I think there is also something that has happened with Marechera where he has been stripped of his identity as a Zimbabwean, as an African. So the scholarship around him now describes him as a universal writer, as an international writer. So he’s no longer rooted in a place. And the idea was to try and locate him in a place and see what narrative emerges.

Harare and Zimbabwe merge in Marechera because of his own experience. Before exile, Marechera’s experience is in a small town, in Rusape at St. Augustine’s, Penhalonga, where he went to school, so in the east of Zimbabwe. He leaves Zimbabwe, comes back and his experience of Zimbabwe is just Harare. So he interacts with Zimbabwe from Harare. And in a lot of ways nothing has changed in Zimbabwe. Zimbabwe has always been Harare-centric. So the Zimbabwean experience has always been centred around Harare. So, you know, Bulawayo has its own fascinating history but in the big scheme of things it’s a peripheral, footnote to the history of Zimbabwe.

So locating Marechera in Harare was also trying to complicate that because in a way, yes he has become an everyday man, or an every man, but then we are also forcing him into a space that is repulsive to him. So we’re trying to play around with his identity as a writer. Is he a writer from Harare or is he a writer from Zimbabwe? So while it was locating him in a space it was also poking fun at that idea of labeling a writer or locating a writer in a specific place.

The full map of “Home Means Nothing to Me” is available in Chimurenga‘s The Chronic issue “The Invention of Zimbabwe,” “which writes Zimbabwe beyond white fears and the Africa-South conundrum.”

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions