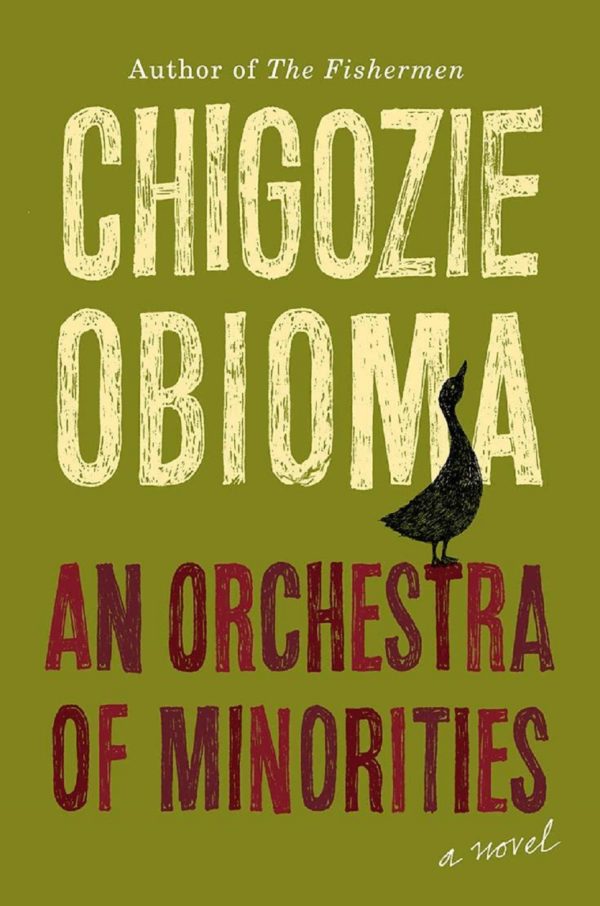

Chigozie Obioma’s second novel An Orchestra of Minorities was published this January. As part of The Summer Library’s “selected extracts from the best new books this summer,” The Monthly has provided a part of the first chapter of the novel. The chosen section is titled “The Woman on the Bridge.”

_________________________________________________________________________

The Woman on the Bridge

Chukwu if one is a guardian spirit sent for the first time to inhabit a host who will come into the world in Umuahia, a town in the land of the great fathers, the first thing that strikes the spirit would be the immensity of the land. As the guardian spirit descends with the reincarnating body of the new host towards the land, what reveals itself to the eye astonishes. Suddenly, as if some primordial curtain has been peeled off, one is exposed to an interminable stretch of leaf-green vegetation. As one draws closer to Umuahia, one is enticed by the elements around the land of the fathers: the hills, the thick, great forest of Ogbuti-ukwu, a forest as old as the first man who hunted in it. The early fathers had been told that signs of the cosmic explosion that birthed the world could be seen here and that from the beginning, when the world was partitioned into sky, water, forest and land, the Ogbuti forest had become a country, a country more expansive than any poem about it. The leaves of the trees bear in them a provincial history of the universe. But beyond the exaltation of the great forest, one becomes even more fascinated with the many water bodies, the biggest of which is the Imo River and its numerous tributaries.

That river weaves itself around the forest in a complex circuit comparable only to that of human veins. One finds it in one part of the city spouting like a deep gash. One travels on the same road for a short distance and it appears – as if out of nowhere – behind a hill or an enormous gorge. Then there, between the thighs of the valleys, it is flowing again. Even if we miss it at first, one only needs to tread past Bende towards Umuahia, through the Ngwa villages, before a small, silent tributary reveals its seductive face. The river has a distinct place in the mythologies of the people because in their universe, water is supreme. They know that all rivers are maternal and therefore are capable of birthing things. This river birthed the city of Imo. Through its neighbouring city runs the Niger, a greater river which was itself the stuff of legend. Long ago, the Niger overran its boundaries in its relentless journey and met another, the Benue, in an encounter that forever changed the history of the people and the civilisations around both rivers.

Egbunu, the testimony for which I have come to your luminous court this night began at the Imo River nearly seven years ago. My host had travelled to Enugu that morning to replenish his stock, as he often did. It had rained in Enugu the previous night, and water was everywhere – trickling down from the roofs of buildings, in potholes on the roads, on the leaves of trees, dripping from orbs of spiderwebs – and a slight drizzle was on the faces and clothes of people. He went about the market in high spirit, his trousers rolled up over his ankles so as not to stain the hems with dirty water as he walked from shed to shed, stall to stall. The market seethed with people, as it always was even in the time of the great fathers when the market was the centre of everything. It was here that goods were exchanged, festivals were held and negotiations between villages were conducted. Throughout the land of the fathers, the shrine of Ala, the great mother, was often located close to the market. In the imagination of the fathers, the market was also the one human gathering that attracted the most vagrant spirits – akaliogolis, amosu, tricksters and various vagabond discarnate beings. For in the earth, a spirit without a host is nothing. One must inhabit a physical body to have any effect on the things of the world. And so these spirits are in constant search for vessels to occupy, and insatiable in their pursuit of corporeality. They must be avoided at all costs. I once saw such a being inhabit the body of a dead dog in desperation. And it managed, by some alchemical means, to stir this carrion to life and make it amble a few steps before leaving the dog to lie dead again in the grass. It was a fearful sight. This is why it is considered ill advised for a chi to leave the body of its host in such a place or to step far away from a host who is asleep or in an unconscious state. Some of these discarnate beings, especially the evil spirits, even sometimes try to overpower a present chi, or ones who have gone out on a consultation on behalf of their hosts. This is why you, Chukwu, warn us against such journeys, especially at night! For when a foreign spirit embodies a person, it is difficult to get it out! This is why we have the mentally ill, the epileptic, men with abominable passions, murderers of their own parents and others! Many of them have become possessed by strange spirits and their chi are rendered homeless and reduced to following the host about, pleading or trying to negotiate – often fruitlessly – with the intruder. I have seen it many times.

When my host returned to his van, he recorded in his big foolscap notebook that he’d bought eight adult fowls – two roosters and six hens – a bag of millet, a half bag of broiler feed and a nylon bag full of fried termites. He’d paid twice the usual price of chickens for one, a wool-white rooster with a long tapering comb and plush of feathers. When the seller handed him the fowl, tears clouded his eyes. For a moment, the seller and even the bird in his hands appeared as a shimmering illusion. The seller watched him in what seemed to be astonishment, perhaps wondering why my host had been so moved by the sight of the chicken. The man did not know that my host was a man of instinct and passion. And that he had bought this one bird for the price of two because the bird bore an uncanny resemblance to the gosling he had owned as a child, which he’d loved many years ago, a bird that changed his life.

Ebubedike, after he bought the prized white rooster, he embarked on the journey back to Umuahia with delight. Even when it struck him that he’d spent a longer time in Enugu than he’d intended and had not fed the rest of his flock for much of that day, it did not dampen his spirit. Not even the thought of them engaging in a mutiny of angry cackles and crows, as they often did when hungry, the kind of noise that even distant neighbours complained about, troubled him. On this day, in contrast to most other days, any time he encountered a police checkpoint, he paid the officers handily. He did not argue that he had no money, as he often did. Instead, before he came to their stations, where they had laid down logs studded with protruding nails to force the traffic to stop, he stretched his hand through the window clutching a wad of notes.

_________________________________________________________________________

Continue reading on The Monthly.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions