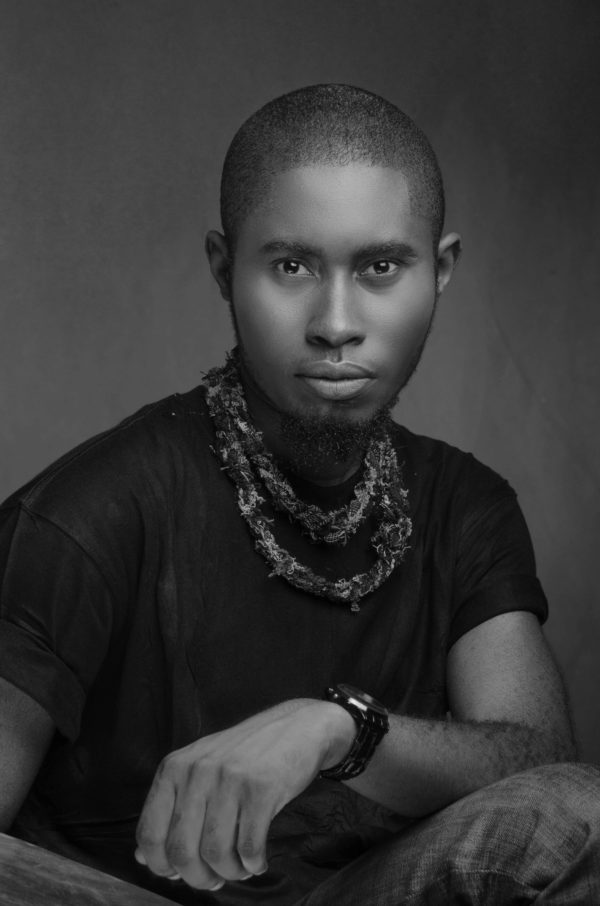

Chibụìhè Achịmbà is a queer poet, essayist and photographer from Nigeria. He is a 2018 Fellow of Ebedi International Writers Residency, winner of the Brittle Paper Anniversary Award, a finalist for the 2018 Gerald Kraak Award, and was recently longlisted for the 2018 Koffi Addo Prize. He won the 2016 Babishai Niwe Haiku prize and was, in that same year, nominated for the Pushcart Prize. His works have been published or forthcoming in Guernica, Catapult, HEArt Journal, Cosmonauts Avenue, Aké Review, Gerald Kraak Anthology, Gnarled Oak, Brittle Paper, Expound Magazine, 14: Queer Art, Mounting the Moon, and elsewhere. He is the co-founder and arts editor of Kabaka Magazine.

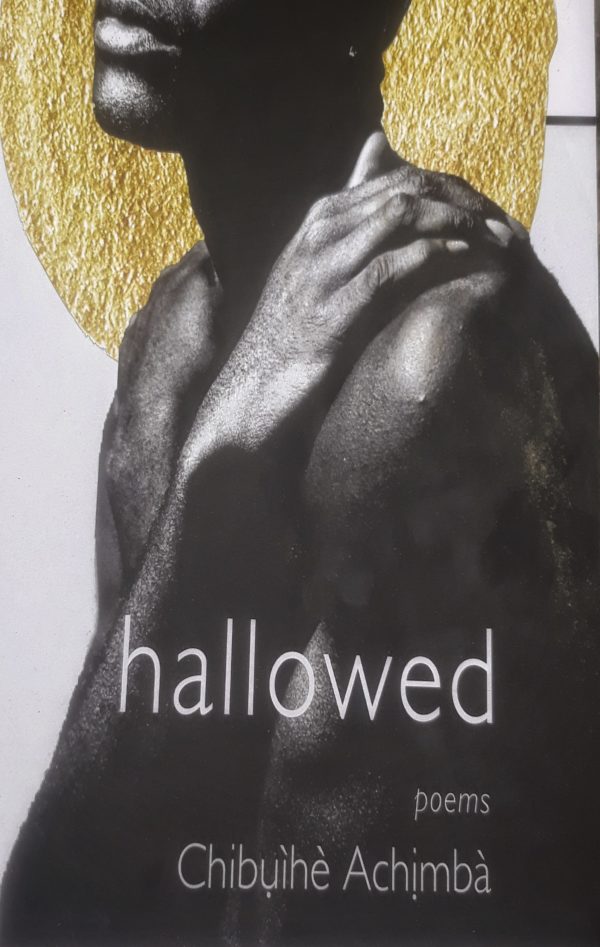

In this interview, Achimba talks, among other things, about his debut poetry collection titled Hallowed. The collection offers us a startling but poignant montage of the precarity of beings abjected by society. His rhythm is as pointed as pain, tones affective, and imagery funereal. He deploys an idiom of pathos to center the links between difference and death. Achimba shows that anyone who dares to love outside the norm is simply inviting to themselves a cudgel. His poetry recalls the lives lost because society couldn’t abide such love.

***

Umezurike

If poetry offers us a glimpse into another world, the world you evoke in hallowed is grim and chilling. The poet persona says, “we’ll have a whole/cathedral of queer heads […] we’ll have names with socketed eyes.” Simple, then, as this question might sound, what is poetry to you? Can you share your own experience of writing the collection?

Achịmbá

Poetry is a threshold where the individual comes to interact with their world. This threshold functions as both a mirror for reflections and an altar where the self – personal and collective – is put on trial. Poetry, to me, is also the act of prodding continuously for truth, answers, a resolution, and revelations without yielding. It takes us across the borders of banality, helps us to see the tiniest of sand grains, recognize the flimsiest of gestures, and to gain access into language itself. I believe the very meaning of life is embedded in language. We are made possible in and through language. So, poetry is the portal into the thick knot called life and the general anxieties of living and surviving.

Preparing this chapbook has been a total experience for me. By this I mean, writing the poems afforded me the opportunity to interrogate my identity as a queer body and the precarious act of survival, and also the place of the queer body in the Nigerian political and social space. It was difficult for me to accept the task of revisiting these sights of violence, because of their recency and rawness; because most of them are still ongoing and unresolved. Confronting a trauma is as excruciating as the pain of living it. It was like scraping open an overnight wound and dressing it with salt, with the intention of repeating this process day after day after day. Much worse was the overall lack of confidence in my own budding voice. There were moments of intense self-doubts and anxiety, moments when I’d shut my laptop and turn to my body, re-examine the injury and potential risks, thinking if the whole experience of anguish was worth it. But, like Ocean Vuong once said, “The work gets done when [the] terror is outpaced by [the] sense of urgency to speak.”

The gnawing need, the urgency to document these events, these people, was like a sharp, undigestable bone in my gullet. The options were not too many. It was either I got rid of it or be damned. It wasn’t more about the luxury of articulating oneself and the desperation of the situation as it was the duty of documenting these stories. Someone has to tell these stories. These people deserve to be given a name, their stories deserve a certain visibility. Writing these words is the only way to rescue our collective selves from erasure, which, I think, is the principal goal of homophobia.

Umezurike

In “coast to coast,” the poet says, “the body is poetry.” What defines a poem as a poem for you? How do you go about writing a poem? And what does it mean to you to be a poet?

Achịmbá

A poem, like the body, is ridden with possibilities: in the way it can expand, contract, contort, ball into energy, float, sink, reappear. A poem could be anything, although it is never nothing. The body, even after death, continues to exist in other organic forms, the same way a poem continues to exist even after the poet has ceased to be. A poem can assume any shape. It can appear in any color. Sometimes a poem bolts across as a scream. Other times it appears as silence. The only constant is that a poem is always alive – your nose flares at its odour, your ears twitch, muscles contort, hearts skip. You can always hear and feel the heart beat, the pulse of its warm, coursing blood. In rare cases, none of the above happens. It’s like Pentecostal anointing: it might make you numb, or make you burst into tongues. Poetry is a type of language born out of angst, language imbued with power. It is not mostly as esoteric as this explanation sounds. A stanza of incantation born out of months of isolation and intercession is no more poetry than a gale of spontaneous moans. In writing poems, I take lots of notes – little scraps of language, scene, moments, ideas– which I go back to. I brood over these things. I turn them over to check their surprising underbellies, and it’s usually through this process that a poem takes shape. Also, I am always willing to let a stray shard of language lead me on. I am always willing to yield to my instincts and the possessing power of language. The truth about writing poetry is that you are never sure of everything. Sometimes I don’t know what I’m doing until the deed is done and a shimmering line swims into focus. My main concern is the theme, the conflict, the bone in my gullet.

To be a poet is to be human enough to care about your existence beyond inhaling oxygen and obeying gravity. It means to stop and stare when every other person is rushing past. And this is where the burden lies: the compulsion to either obey and act or be haunted for the rest of the day, week, or month, as the case may be. Like me crawling out of the bed way after midnight because a stray imagery won’t let me sleep. To be a poet is to be acutely aware of yourself, your body, your space and your place in this unfathomable universe. To be a poet is to give feelings, dreams, events, moments, memories name.

Umezurike

For me, the collection operates on two levels: voice and visibility. It gives voice to those whom society would rather silence (literally and figuratively) because of their sexuality, and visibility to such people since society would prefer they remain out of sight. How did you come about the title?

Achịmbá

One of the most fascinating things about poetry is that it gives you the power to name yourself, your experiences and truth. In composing this chapbook, I relied mostly on religious iconography to give the poems context. The working title was a haloed wound, but autocorrect kept changing haloed to hallowed, so I ended up submitting the manuscript as a hallowed wound. During the reviewing process with my publisher, they suggested we use just a single word hallowed for the weight it carried and consequently lent to the entire suite of poems. In a way, it illustrates what I pointed out above, how the creative process is never always predetermined. It also emphasizes how technology has become a part of the creative process, helping us midwife ideas through suggestions and sometimes arbitrary imposition.

Umezurike

Indeed, religious imagery pulses through your poetry. Can you recollect what you were thinking of when you wrote this particular line: “a cathedral with the queer body crucified in place of the lamb”? And why make use of religious symbols, when queerness and religion rarely mix?

Achịmbá

Most of the poems explore the confusions of coming to terms with my sexuality as a teenager and the myriads of questions I had to confront. That period was one of the most intense and hopeless, because I was searching everywhere for some kind of affinity with the mythical figures I’ve been introduced to. At that point I thought the death of Christ on Calvary was meaningless to me and useless to my situation. What was the point of looking unto him when those who torment you do so in his name? What was the need of seeking shield under his shadow when it was obvious that me and my kind have been excluded from that fellowship? I decided to pick my saviors and pick them from the ranks of those who knew what it means to live on one’s own terms. That sense of kinship and lineage is central to rebuilding one’s battered self-confidence. It is important for us queer bodies to connect with our queer ancestors and heroes. That way we are reminded that we are not alone, that we also have a vast cloud of witnesses, kindred spirits, living and dead. I love the idea of a family tree. It is why I find consolation from studying the works of James Baldwin than the Bible. While the former lived through the same anxieties I am currently going through, the authors of the latter were mostly aloof, even complicit. I needed a savior who understood my fraught and desperate existence, a savior willing to console me. Clinging unto the Christian totem of salvation despite the glaring indictments would be a hard case of Stockholm’s syndrome, or so I thought. My idea of spirituality was, and somehow is still, transactional and not servile. I demand succor and consolation in place of my reverence. It is important to note that these things are subject to change. We evolve. But articulating those feelings that way brought so much clarity to my situation.

Of all the religions in the world, the Abrahamic sects are the ones with outright dehumanizing views on homosexuality. I grew up in a strict Christian home. I was promised to God five years before I was born. So, once I finished secondary school, I was hurled to a theological Seminary to become a priest, but I ran away from the institution and also fled home. I was fifteen that year and was gradually becoming aware of my sexuality. From what I’d gleaned from the Bible and the sermons I’d heard from the pulpit, I knew I didn’t belong there. There was this overwhelming sense of unworthiness (which Christianity claims is the lot of every individual born into flesh by the way), but for me as a queer person it went beyond that. Being called abominable, being derided and demonized was an excruciating experience I couldn’t put up with. I don’t go anywhere my humanity is questioned. My humanity is a sacred ground. I can never negotiate it with anyone. After I left the institution, I tried so hard to sort out my sexuality personally with God. I prayed, fasted, went for deliverance sections, with the hope that God would see my genuine zeal and heal me, but it turned out He didn’t give a fuck about me, or the whole organized religion and their reprehensible doctrines. And because I got fed up with the recyclic bullshit and mental torture, I left the church. But I left with some of their artifacts and language which I had already imbibed. In appropriating these artifacts and language, I am compensating myself for the years and pain it took me to learn them. They are part of my personal history and vocabulary. My worldview was shaped partly by those myths. I am also deconstructing, reimagining and interrogating the Bible and the mythical characters in it in my writing, inserting the queer body in all the various sites it has been erased.

Umezurike

Reading your poetry, I recall that Uche Nduka said that, “To be a poet is to understand that a poem is a moving target.” And your poetry teems with the imagery of flight. In “transfiguration,” the poet says, “the country i’m running away from has got my body,” and in “when the queer body makes the news,” the poet appears to be “running/hiding.” To what extent does this concept of a “moving target” resonate with you? How might a poet, already a target of society, apply their poetry to (re)affirming their visibility without “enter[ing] the news as tragedy”? And at what price?

Achịmbá

I don’t take Uche Nduka’s statement literally in that sense. I think it’s in line with what I said above about a poem not being predetermined. A poem evolves from a singular imagery into broader tropes and ideas. And it’s important that a poet have that knowledge at the back of their mind in order not to cripple their work. For how I negotiate the tenuous line between visibility and putting myself at risk: I chose running and hiding. According to the poet Romeo Oriogun, the first rule of survival is running. The only price I want to pay for my freedom is with my voice. Nothing more, nothing less. As an artist, that’s the only gold I can afford, and I think it’s a fair price to pay. I am deeply awed by the courage of those who offer themselves for their beliefs and for the public good, but I don’t think I am that brave. I love life. The thought of death and dying, especially painful and tortuous deaths, terrify me so much. And that explains why the trauma of my abduction and near-death experience still haunt me with heightened clarity a year after its occurrence. I have learnt not to take chances, not to gamble with my life. Social media has made it possible for us to be virtually visible and contribute to the conversation without being physically present, without jeopardizing our safety. And that is what I do. Because it is important for me to be alive and do this work. It is important for me to stay sane and healthy. It is equally important for me to have my human dignity intact without being harassed by every lout and idiot out there. Because that law itself in very obvious ways empowered anyone to harass and extort and take advantage of the porous nature of the clauses. It indirectly empowered miscreants to do government’s dirty job for them. This is why there are more cases of abductions, extortions, harassment of homosexuals than arrests and detentions by law enforcement agencies. I sincerely don’t want to relive that humiliating experience. It’s heartbreaking and humiliating. So, I’ll keep running and hiding, and “art-ing” safely.

Umezurike

Queerness is the defining trope of your poetry. How has poetry enabled you “to name a scar rightly” – to write, what I would call, “the truth of (your) self” into narratives that attempt to efface you? In what ways might poetry be mobilised to contest norms and ideologies that set “us” apart from “them” based on gender, sex and sexuality?

Achịmbá

Poetry gives you the power and language to name yourself and your desires and anxieties. I discovered very early in this journey that I am made possible in (through) language. What are we without awareness and a sense of identity? And this is the gift that poetry gives and keeps giving. I found the language to interrogate this self, to put this self on trial; I found the language to know this self some more. Because in the words of Walt Whitman “I am [vast], I contain multitudes.” Poetry asks questions and is never content with just an answer. And the task of finding a self, or coming to terms with a self has a lot to do with questioning. I believe that by writing sex, sexuality and gender, we will not only confront and spark useful conversations around them, we will also be humanizing these concepts, fitting them into stories and narratives. We will be giving name to this thing that the society has refused to name. Through poetry we will rescue the queer body and our collective selves from erasure.

Umezurike

Queer-themed poetry is emerging as a genre, something long missing in much of the poetry produced in Nigeria? What future might there be for queer poetry in Nigeria? Can you say a few words about the current state of poetry in Nigeria?

Achịmbá

I am happy to be alive at this moment and time. I am equally grateful for the calibre of poets at work and those emerging. These poets are not afraid to explore their intimate and private spaces. They are not afraid to give name to these hitherto ‘unnameable’ desires; they are not afraid of owning their desires and articulating them. One of the challenges we faced was the lack of mentors and a lineage to follow. We didn’t have openly queer writers around to look up to. There were no examples of what a poem exploring queer identity and desire looked like. We had to start from the scratch and invent the style and the narrative and the trope, which can be very daunting. Writing is one of the vocations you learn from doing a great deal of imitation through reading and careful study. With the proliferation of queer narratives now, I believe the next generation of writers exploring queer identity will definitely find it less cumbersome, because they’d be working within a tradition that has already been established.

As for the state of poetry in Nigeria, I will say it is currently at its apogee. The Nigerian literary landscape has never been so decorated with this number of stellar and hardworking poets, thanks to the internet and, particularly, online journals. My peers and their works are gaining access into reputable spaces. Gbenga Adesina has been published in The New York Times after winning the Brunel International Poetry Award; Saddiq Dzukogi was accepted straight into a PhD program; Romeo Oriogun won the Brunel and is currently doing a Fellowship at Harvard; DM Aderibigbe just published his debut collection. Then, there’s Logan February, young and getting it; there’s Ejiofor Ugwu, and JK Anowe, Chinua Ezenwa-Ohaeto, Chisom Okafor, Hauwa Shaffi Nuhu, Daisy Odeh, etc. Their talent and brilliance and the rigor of craft they show in their works is outstanding. But, sadly, there’s also a bad side to the internet writing thing: the crave for quick success and recognition which can hamper one’s growth and development. And I think every aspiring writer should pay attention to this. Because these people often post links to their success stories on social media, it might appear easy. No one, or just a few people talk publicly about the pains and stress and general work they put into honing their craft. The glitz and glamour outshines the sweat, and this can sometimes be misleading. We also run the risk of producing shallow works that neither recognize nor pay homage to tradition, works that lack rigor and clout. I’ve discovered a sad trend from interacting with young poets: we write more than we read. I think it’s wrong and counterproductive to be doing that at this stage of our career. We should use the internet more as a study tool. Read. Read. Study the works of the poets you admire. Choose your gods and pay attention to their craft. Read thrice as much as you write. Respect the writing process. Invest in your personal growth. Be patient with yourself. I wish I was told this earlier on.

Umezurike

Only a handful of Nigerian poets use lowercase as a mode of poetic expression. Your poetry is marked by certain typographic features such as blank spaces, the way the lines are indented and aligned. Why is this form significant for you? Is it simply stylistic – or is there a rhetorical purpose to it? What determines the form a poem will take?

Achịmbá

Every poem I write is, in a way, my body in translation. The shape and indentation is the graphical representation of my body. My body is frail, fractured, neither perfect nor whole, always evolving. My body is littered with tiny, invisible spaces, pockets of experiences, portals of entry, exit points. I choose the lowercase because it’s a departure from the norm, a departure from the patriarchal-heteronormative culture that insists that some certain things appear in a certain way. It is also a way of acknowledging and paying homage to the feminine force inside this body. The feminine self is most active when I am writing poetry. This self prizes the soft symmetry of the lowercase over the rough and angular shapes of the uppercase. I try to respect this reality as much as I can. Oftentimes a poem decides its own form. Some might come out formless and would end up staying that way. I respect their autonomy and choice. They are living, breathing things. We are the sum of all the experiences that formed us. I try not to undermine my spirituality and the role it plays in my artistic practice.

Umezurike

A tradition of protest or rage has defined much of the poetry published in Nigeria in the last few decades. Reading the poetry of your peers, Romeo Oriogun, Gbenga Adesina, Saddiq Dzukogi, Ejiofor Ugwu, DM Aderibigbe, I sense there’s a break with tradition. Do you feel any burden to write poetry along this tradition? How much of this burden applies to your practice?

Achịmbá

I think it’s important we understand that we are living in a different political and technological era. Most of these poets wrote during military dictatorships. It was almost impossible for their voices not to have assumed that militant timbre. You will notice that millennials have totally different issues that beset us. It is at once personal and global. We are mostly inward gazers. The writer and editor, Otosirieze Obi-Young called us the confessional generation. We are content with interrogating the self, discussing the society within the context of the self. Our parents invested so much of their time ‘righting the wrongs’ in the society at the expense of our psychological and emotional wellbeing. So, it’s understandable why most of the emerging poets are paying attention to themselves and their place in the system of things, working out their own healing by confronting and interrogating their personal traumas and realities. Poems of this nature are as much powerful. The personal is also political. I respect the idea of tradition and lineage, but I also think everyone should be allowed to choose which traditions to uphold and which lineage to follow. And it also okay for the older generation to feel betrayed by our attraction to Western, particularly American, poetic traditions. But it is equally important for them to understand the role our education system played in this. By denying us access to the works of these poets, to this tradition, it gave us liberty to look elsewhere.

Umezurike

In “self-portrait as mouth,” the poet declaims that “i write poems now.” How might poetry stimulate conversations about social acceptance? To what extent can poetry offer us a means to appreciate the everyday precarity that accompanies queerness? What is the work of poetry, if any, in a time of homophobia and heterosexism?

Achịmbá

Sometimes I think one of the main reasons homophobia has wormed itself into our collective consciousness is due to the fact that homosexuals themselves have not been given enough space in our literature. So, to write about the queer identity is to X-ray it, to bring it out of the back stage into light, to express and celebrate this love on the pages of our literature. To humanize, normalize, and accord dignity to this identity. A large percentage of homophobic people in this part of the world are egregiously ignorant of what it means to be queer. Their minds are tangled in the myths and misconceptions they inherited about homosexuality. They still see us as outsiders, the other, the bright-coloured, smoke-belching alien. If people, through reading, can shed their ignorance, they can also interrogate their unfounded fears about homosexuals through this same process. According to Susan Sontag, “Literature can train, and exercise, our ability to weep for those who are not us or ours.” Eliciting empathy from the reader; taking them through the general anxieties of living and surviving as a queer body; making them interrogate and question their apathy and hate… These are the many ways poetry stimulates conversations about social acceptance. The task of poetry in this desperate time is to keep asking questions without settling for any answer. The task of poetry is to confront the language of power – heterosexism, patriarchy, heteronormativity, etc.

Umezurike

In a “wound within a wound,” you ask troubling questions:

is this what we’re here for

to be drenched

to be beaten

to soak up each other’s blood

Can you speak more about this particular poem?

Achịmbá

I spent time in a safe shelter for LGBTQi persons in Nigeria and it was overwhelming to get first hand accounts of the violence and violations queer people are being put through in this country. What shapes most of the conversations queer people have is violence. Every occupant had one or more horrific experiences to recount. Stories of being extorted, beaten. Stories about abductions, harassment, lynching, and various acts of humiliation and violence. These are stories that hardly make it into the headlines. It’s draining to be surrounded by this blistering reality. It is unfair that queer people are made to live in hiding, to live with this palpable fear and insecurity. We should do better as a country.

Umezurike

What poets are important to you as a poet? Are there particular authors who have meant a great deal to you since you started writing poetry? Finally, what might you be working on next?

Achịmbá

I began by studying the works of Christopher Okigbo and Uche Nduka – the former for his spiritual leaning, philosophy and depth, and the latter for his uninhibited experimentation with language. Chris Abani is nna m ukwu; I just started my apprenticeship under him. His range and imagination is copious. His discipline and attention to detail challenges me to do better in my own practice. I always go back to the works of the following poets, for how they love and manipulate language: the polish poet Wislawa Szymborska, Rainer Maria Rilke, Ocean Vuong, Chelsea Dingman, Carl Phillips, Essex Hemphill, francine j harris, Lucille Clifton, Tomas Tranströmer, Jenny Xie, Jericho Brown, and many others I can’t list right now. I am currently working on my full-length collection. My plan is to let it simmer and take shape. To achieve this, I am going into full-time apprenticeship. I’ll use the coming years to hone my craft and research and push my craft to its possible limit. One thing I have gleaned from the poets whose works I admire is that they put in a lot of time, energy and ambition. I want to give myself the permission and time to grow.

***************

About the Interviewer:

Uchechukwu Peter Umezurike is a PhD student at the department of English and Film Studies, University of Alberta. His research interests include postcolonial literatures, print culture, gender and sexuality studies. An Alumnus of the International Writing Program (USA), his work has appeared in several print anthologies such as On Broken Wings, Dream Chasers, Migrations, African Roar 2011, Daughters of Eve and Other Stories, Work in Progress & Other Stories, A Generation Defining Itself (Vol. 8),Weaverbird Collection, New Nigerian Writing, Water Testament, Calvacade, Author Africa, and Camouflage, etc.

Uchechukwu Peter Umezurike is a PhD student at the department of English and Film Studies, University of Alberta. His research interests include postcolonial literatures, print culture, gender and sexuality studies. An Alumnus of the International Writing Program (USA), his work has appeared in several print anthologies such as On Broken Wings, Dream Chasers, Migrations, African Roar 2011, Daughters of Eve and Other Stories, Work in Progress & Other Stories, A Generation Defining Itself (Vol. 8),Weaverbird Collection, New Nigerian Writing, Water Testament, Calvacade, Author Africa, and Camouflage, etc.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions