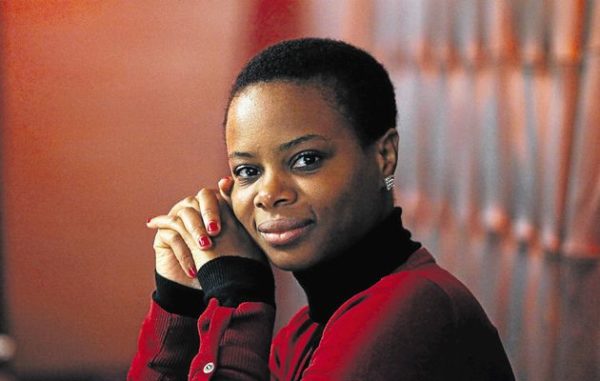

Hawa Jande Golakai was born in Frankfurt, Germany, and spent her childhood in her homeland of Liberia, later living in several African countries when her family fled the civil war. Her crime debut, The Lazarus Effect, was nominated for three literary awards, and published in the UK in May 2016 by Cassava Republic Press. Hawa was listed by the Hay Festival as one of the thirty-nine most promising African writers under the age of forty, and

her work was included in the Africa39 anthology published by Bloomsbury. She works as a medical immunologist and health consultant in Monrovia.

Following her win of the inaugural Brittle Paper Award for Creative Nonfiction in 2017, for her Granta piece “Fugee,” she was in conversation with Gaamangwe Joy Mogami, founder and editor of the Botswana-based interview magazine Africa in Dialogue. This conversation, which took place on Skype, is taken from Africa in Dialogue‘s e-book of conversations with the 2017 winners of the Brittle Paper Awards, including Sisonke Msimang, JK Anowe, Chibuihe Achimba, and Megan Ross.

_________________________________________________________________________

Gaamangwe Joy Mogami:

Hawa, congratulations for winning the Brittle Paper Creative Nonfiction Award. How did it feel winning this award with a story you wrote two years ago?

Hawa Jande Golakai:

I was floored. After I’ve written a piece, I tend to have a strong inkling about the work but I wasn’t so sure with this piece. I was genuinely surprised by how well-received it was—first in Granta magazine and then when it was published in Safe House anthology. I don’t normally do personal pieces because I am a fiction lover. I like to reflect and deflect things through the lens of fiction and fantasy, the unreal. When I was asked to write the piece I was reluctant, but I agreed because Ellah Wakatama Allfrey asked me to do it; she was really convincing and I could not say no to her. She was unbelievably good at pulling those emotional threads from me such that when the piece was done I was mentally and emotionally spent. I cried and laughed, I remembered every bit of the rage and comedy I felt during Ebola while writing that piece. So when I was nominated for the Brittle Paper Awards, I was pleasantly stunned. The quality of work nominated for the inaugural awards was stratospheric—the nomination was honour enough. Then I won!

Gaamangwe Joy Mogami:

I am glad you won because the same emotions that you felt while you were writing, I felt them as a reader. It was this pendulum of emotions. I would be enthralled and sad in the moment, imagining what that must have felt like and then I will just start laughing because you’d just put it in a very hilarious way.

Hawa Jande Golakai:

Humor is my defense mechanism. I’ve used it for so long that I wonder if I’m too dependent on it. I was trying to write a Winnie Mandela tribute recently and it was a battle to completely steer clear. The piece ended up having a tinge of dry humor anyway. It’s something of a trademark. I think I’ll keep it.

Gaamangwe Joy Mogami:

I think looking at the subject of the piece, the humor, as much as it can distance us from the trauma, it also added an edge to it. It made it very human.

Hawa Jande Golakai:

It really did. In Africa, in addition to us having a very immediate outlook on life, we have a highly fatalistic outlook. Like we say here in Liberia: “if you can’t laugh, you will cry.” The two things are interchangeable because if you focus on the negative every day of your life and your life is already difficult as it is, you’ll end up in a mental home for depression. So create your own bright side. That fatalistic humor helped bring a dire crisis to life. Liberia was here long before Ebola descended on us. In the midst of this crisis, people held onto moments of lightness in their daily lives because they had to. Life within our borders got so bleak you’d think, “Well, it can’t get any worse than this,” and you just ploughed on ahead. The extraordinary became liveable for us, then ordinary, and then—even more disturbingly—sometimes boring. The incredible relies only on frequency—only if you don’t see something a lot will it blow your mind. Before the crisis I knew my city well. During and after, I developed an ‘anything goes’ mentality. It was taxing to meet others coming from a completely different trajectory and have to explain, “I don’t know another reality, this is my normal.”

Gaamangwe Joy Mogami:

Yes, we do live with traumas, but as you said, we also have lightness and I think this is what we hold on to more than anything. But also this is our lives, after all. I think your piece was powerful because it really articulated your experience as a Liberian who went through a crisis which was private for you, but your country people and other West-African individuals understood this crisis and were experiencing it and so a very public crisis. It’s an important narrative because, usually, when people think Ebola, the narratives coming out are about the grimness of it, and that is how you are seen by the world, as “those people who are from that country that has Ebola,” and that becomes your identity.

Hawa Jande Golakai:

It’s true: as Africans we have accepted to carry around passports stamped with stories that are not really our own. Stories of how the world sees us even though it’s not how we view ourselves, and most of those stories are macabre, grim and usually not nuanced. But then you talk to the people on the ground, the Africans who actually live in their countries, and a different story unwinds. I’ve lived on this continent all my life so I listen with great care to how stories are reported about “African developments and crises”—in Liberia, Zimbabwe, Kenya. Stories can contain us or be about us, but somehow we’re never the main ingredient. It’s allowable for us to be consumed by people who don’t necessarily understand us. The nobility in this new brand of “African literature” is to normalize, to show that what humans struggle with is truly the same everywhere. People are dirtbags and angels and everything in between, all over the world. Our perspective is no different.

Gaamangwe Joy Mogami:

Yes, I agree. Our lives are not one dimensional. How was the process of writing this piece?

Hawa Jande Golakai:

It happened quite organically, and I’m glad I was approached to do it quickly instead of having too much time to get in my head about it. I’m the sort of writer who chronicles on the downslope—I have great recall and eye for detail, but I don’t write things down immediately after they happen. Every writer has their own process—I’m an aftermath chronicler. I bottle and pickle the emotions while they’re still fresh, digestible but not raw. This piece especially deserved that. I do my best work when the atmosphere, the smell, the cloak and the feel of things is still present.

I was asked to do the piece not too long after I got back to Liberia from Ghana. The finished piece, “Fugee,” didn’t mention how I stayed in Ghana for several weeks because I couldn’t get a flight back to Liberia. So I just sat in a region outside of Accra called Kasoa, with very little money and far too much time. Thinking, marinating in my emotions and the sweltering heat, talking to myself. I was alone in a large house, the home of a family friend, so conditions were ripe for me to get deeply weird in my head. That whole period was like a fever dream.

I thought of my recent trip—I’d left Monrovia for Port Harcourt, stayed on for Ake Festival, then flew back to Accra to wait until the world deemed it safe for Liberian borders to reopen. I was grieving at the time over the death of my cousin from Ebola. While I was in Nigeria I was messed up; I loved being a part of all this literary talent but I also felt wrung out. I’d experience wild sways of emotion, go to the bathroom and cry or laugh, wash my face and go out and rejoin festivities. I didn’t really know what I was going through, just that I had to power through it.

I remember one such Nigerian experience: reporters at Ake Festival were doing a promotion of all the authors like me who had interviews and literary panels. There was a mini press conference that was held and all the media that spoke to me asked me about Ebola. Some of them didn’t ask me about my work, it was all Ebola. How Liberians were handling Ebola and how Liberia was one of the countries helping to spread Ebola. I was thunderstruck. During one interview I excused myself (again for the bathroom) and when I got in there, instead of tearing up, I started laughing hysterically. Like, “What the hell was that? What am I doing here, seriously?” Complete out of body experience.

Those moments came in handy during the writing process months later. Ellah emailed me, requesting a creative nonfiction piece for the Commonwealth Writers Trust. She was clear she didn’t want me to do a verbal autopsy of the crisis; she wanted me to make it breathe for her, take her through what my entire experience had been like. And she kept me honest by being so incisive herself! When I tried to skim and skimp on the emotional fallout, she called me to order. Where I vomited too much unnecessary detail, she reined me back in. I went through all the feels for that piece, it hurt to not only re-live but re-emote all of it. But it was worth it. Like all great editors, she was excellent at keeping me focused on what the true call of the piece was about, so I give her a lot of credit.

Gaamangwe Joy Mogami:

I am so sorry for the experience with the journalists. People can be insensitive with public trauma especially when you travel to a different country. You become a representative of your country and you just end up doing a lot of emotional labor for people. It’s terrible. Now I wonder, did you have difficulties travelling and being in Ghana, Nigeria and other countries you went to during that period?

Hawa Jande Golakai:

The God-awful mess of which I nevermore speak—getting arrested by South African immigration at OR Tambo Airport—that was another thing the piece dealt with that happened before Ebola. As for during the crisis: bless ECOWAS (Economic Community of West African States)! Borders worldwide were closed to us but, thankfully, travel was still possible and safe in the region. I didn’t have any problems coming or going but special attention was paid to my movements within the airport. When I first left Monrovia, my first stop before Nigeria was Accra. When we landed, the airport was jam-packed. Sheeple, that’s who we were getting off that plane: docile rows of sheep, staring wide-eyed as we filed into the airport and stood in front of the heat scanner, hoping to God the monitor didn’t flare up red. And did I mention I’d come down with

malaria—the horror if I’d been stopped!

When you talk about the Ebola virus and you try to liquify the pain, it’s hard to stay away from the word zombie. Aside from the flight I left on with my family in 1990, that was the most eerily silent airport experience I’ve ever had. As a speculative fiction writer, I tried not to imagine what could’ve happened had ONE person on that flight suddenly morphed into a braineater . . . .

Gaamangwe Joy Mogami:

That sounds so unreal but it was real life for you and everyone who went through that. And now, how is life for Liberians post the Ebola crisis?

Hawa Jande Golakai:

What is life like in Liberia now? Well, immediately afterwards it was devastating. I don’t know the actual death toll in the afflicted region—Liberia, Guinea, Sierra Leone, parts of Ivory Coast and Nigeria—but it was in the tens of thousands. And the disease struck every aspect of humanity, infrastructure, border control and diplomatic trust, health budgets, all of it. That’s incredibly tough for an already poor nation to bounce back from. But Liberians are a very resilient breed. The sky fell on us, we all watched in terror as it happened and there wasn’t much we could do. Yet we survived. Massive amounts of donor funding went into the sweet hereafter of mismanaged funds; I doubt we’ll ever learn where most of it went. Yet we’re still rebuilding.

Liberia is recovering and life has returned to normal for most. So many health measures we have, I believe, I hope, we will keep. Hand-wash stations in public buildings, temperature and visual check of passengers at airports, the progress with vaccine trials. The moral learned from our saga is you can’t take the piss when it comes to forces you can’t see, can’t bargain with or pay off—a virus can lay waste to everything you cherish. And it has no respect; nothing that’s fighting for its own survival can afford respect or decency. There’s a hardcore lesson there that humans can learn from. Nature fights dirty—stay on Her good side.

Gaamangwe Joy Mogami:

Thank you so much for writing your story. It really helped a lot of us to really understand the inner aspect of experiencing a crisis as devastating as Ebola. Thank you so much for joining me.

Hawa Jande Golakai:

Thank you, Joy.

_________________________________________________________________________

Download: AFRICA IN DIALOGUE INTERVIEWS THE 2017 BRITTLE PAPER AWARD WINNERS

8 Must-read Expository Interviews with Prominent African Writers - EBOquills February 20, 2020 12:33

[…] Writing and the Burden of public grief: in conversation with Hawa Jande Golakai Winner of 2017 Britt…: “It’s true: as Africans, we have accepted to carry around passports stamped with stories […]