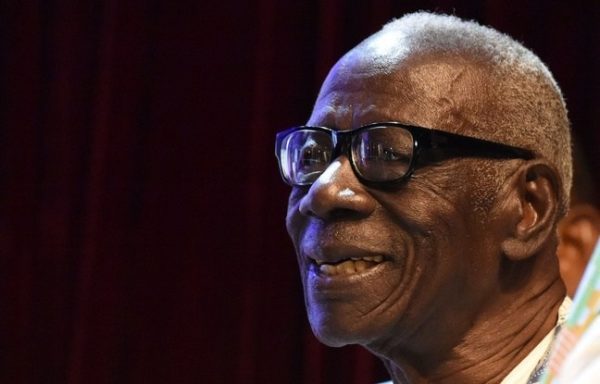

Bernard Dadié, Côte d’Ivoire’s best known writer and former Minister of Culture, has passed on at age 103, on 9 March 2019. His novels, plays and poetry—which have been described as attempting to connect the contemporary world, as shaped by colonialism, to messages in traditional African folktales—were inspiration for the Negritude movement, with his poem “Je Vous Remercie Mon Dieu” considered one of the black nationalist movement’s greatest anthems.

In 2016, aged 100, Dadié was unanimously voted winner of the inaugural, UNESCO-sponsored $50,000 Jamie Torres Bodet Award, for his contribution “to the development of knowledge and society through art, teaching and research in social sciences and humanities,” and later that year, he won the Grand Prix des Mécènes of the Grand Prix of Literary Associations.

COMMENTS -

Reader Interactions